Spring with its promise of winter….

And it is December again,

the snow outside. Or is it June full of sun

— John Ashbery, “The Skaters”

: :

Nathaniel Dorsky’s silent, 45-minute avant-garde film, Hours for Jerome (1982), does not tell a narrative story. In fact, the film is a part of a lineage of American experimental cinema that has been described as “poetic,” an analogy that serves to make their abstractions more palatable and accessible for the audience. Film scholar P. Adams Sitney recalls that when he first became aware of experimental modes of filmmaking in 1960, “Film-poem was nearly interchangeable with experimental film.”1 But how exactly are experimental films “poetic”? In Dorsky’s case, the formal influence of avant-garde poetry, and especially that of John Ashbery, is distinctly legible in the editing of his films.

During the 1960s, Dorsky and Ashbery were artists based in New York City, and while the two were not intimate friends, Dorsky has repeatedly cited Ashbery as a profound influence on his filmmaking. This is especially true when we consider the technical impact of Ashbery’s poetics on Dorsky’s filmmaking. Pairing Ashbery’s 1966 long, postmodern poem “The Skaters” with Dorsky’s Hours for Jerome, shot between 1966 and 1970, shows that Ashbery’s inventive use of the poetic technique parataxis—placing phrases side by side without conjunctions explaining their connection—begets Dorsky’s inventive editing technique known as polyvalent montage. In both the film and the poem, these subtle resonances create order out of disorder or sense out of what seems nonsensical—smooth parataxis and polyvalent montage create a world where the inverted “spring with its promise of winter” is plausible.

: :

Dorsky’s descriptions of reading Ashbery’s poetry have remained impressively consistent over the years. In an interview in 1999 with Scott MacDonald for his book, A Critical Cinema 5, with the Poetry Project Newsletter in 2001, and most recently for the book Illuminated Hours (2023), he describes the same “very slow” and very impactful reading experience. In two of the accounts, he specifically links his idea of polyvalence to his reading of Ashbery: “the idea of [polyvalence] came from a much earlier time, when I was twenty-two and I read John Ashbery very slowly while smoking hash with a friend.”2 His interview with MacDonald reveals that the specific Ashbery poetry he was reading was Rivers and Mountains—the poetry book in which “The Skaters” was originally published:

Around 1966, a poet friend, Michael Brownstein, exposed me to John Ashbery’s The Tennis Court Oath [1962] and Rivers and Mountains [1966]. Of course, there was smoke in the air, and I began to read very slowly, one word at a time, and began to enjoy the resonance of each individual word, each following the next, somewhat like playing single notes on a piano very slowly, one after the other . . . I began to wonder if one could make a film, not literary of course, but more open to the free-floating journey of Ashbery’s poems. I’d ask Jerry, “Do you think a film could change directions with each cut and still hold together?”3

It is clear that Ashbery’s poetry, and specifically Rivers and Mountains, arrived at a formative time in Dorsky’s filmmaking career, when the question of a reimagined montage was foremost on his mind. How could one edit a film with an abundance of paths and opportunities in each shot and yet be sure that a sense of the film as a whole endures?

Ashbery’s “smooth” use of parataxis, as identified by Ian Probstein, employs subtle resonances and associations in place of coordinating conjunctions4—this is perhaps why Dorsky read so slowly. The apparent connections and associations create an atmosphere where parataxis does not feel abrupt or uneven but collaged fluidly. “Associative parataxis” is another way to describe this technique, which scholar and poet Charles Bernstein describes as: “elements joined by perceptual, aesthetic, and philosophical connections . . . constant but gradually shifting, asymmetrically kaleidoscopic; a stream of dissolving shots.”5

In Ashbery’s “The Skaters,” parataxis eventually achieves a smoothed-out atmospheric effect as the reader dives deeper and the associations begin to congeal; but, at first, the long postmodern poem presents a disoriented speaker that is all over the place. In each situation they find themselves in (sailing on a boat, deserted on an island, amid a storm), Ashbery’s speaker spends their time trying to make sense of what’s occurring: “So much has passed through my mind this morning / That I can give you but a dim account of it: …. / And I try to sort out what has happened to me.” The speaker runs through modes of explanations and gets lost in daydreams, just as the speaker daydreams in Ashbery’s celebrated poem “The Instruction Manual.” Toward the end of a chaotic Part I, sprinkled with disjointed imagery and stanzas, Ashbery’s speaker humorously says, “It is time now for a general understanding of / The meaning of all this,” but they withhold or simply do not have any explanations for us.

As the poem progresses, the speaker’s disjunctions echo and repeat within the poem’s walls and eventually create a sense of internalized order via disorder. The seemingly disconnected imagery becomes self-referentially familiar and relevant, which smooths out the transitions. As McHale explains in his article “How (Not) to Read Postmodernist Long Poems”:

Powerfully disjunctive though it is, “The Skaters” does not appear to be as radically disjunct as “Europe,” the long, fragmentary centerpiece poem of The Tennis Court Oath. This lower degree of disjunctiveness serves as a lure to the reader. No one contemplating the detached word clusters of “Europe” would expect to make much immediate sense of the poem, so that the reader’s frustration is correspondingly less, perhaps paradoxically so, while “The Skaters” often appears to make sense locally, inducing in readers the unwarranted expectation that the poem’s global sense should be within relatively easy reach.6

McHale’s comparative analysis of Ashbery’s disjunctive long poems helpfully introduces the terms “locally” and “globally” in order to apply labels to the different scales operating in “The Skaters.” However, rather than reading the local moments of clarity as a lure that leaves the reader frustrated that the poem does not make more sense globally, Ashbery’s repetition of local moments of clarity is exactly what allows the poem to make sense on the global level. Because Ashbery uses recurring images and motifs (the wind, the constellations, and perspective drawing, to name a few), local moments of clarity reflect and refract each other, which produces a global sense of the poem, even if it is faint and feels surreal at times.

The subtle coordination happening at the global level of the poem softens the choppiness of parataxis. Each section of “The Skaters” is relatively uniform, dominated by long stanzas that bring us deeper into the speaker’s side quests. But that is not so with the last 20 lines. The final lines of the poem begin to dissolve into much shorter stanzas that echo images from earlier in the poem:

The tiresome old man is telling us his life story.

Trout are circling under water-

….

The pump is busted. I shall have to get it fixed.

Your knotted hair

Around your shoulders

A shawl the color of the spectrum

Like that marvelous thing you haven’t learned yet.

To refuse the square hive,

postpone the highest…

The apples are all getting tinted

In the cool light of autumn.

The constellations are rising

In perfect order: Taurus, Leo, Gemini.

Ashbery’s choppy and rapid transitions from the “tiresome old man” to the “busted pump” to the “tinted apples” use association in place of coordinating conjunctions. For example, “The pump is busted. I shall have to get it fixed” evokes and contrasts the clear image of the pump from Part I: “the pump heaped high with a chapeau of snow.” This is true too for the imagery of the tinted apples. Reading about apples and their coloring in the end calls up the line from Part III: “Here comes the answer: is it because apples grow / On the tree, or because it is green?” And, while the apple imagery is echoing, “Here comes the answer” also calls back to Part I when the speaker teased sharing “a general understanding of / The meaning of all this.” Without the speaker ever sharing a clear explanation for all the poem’s disjunctive parts, it is our associations that create the connections. The recollections of these seemingly random images doled out at the end produces an atmosphere that coordinates through repetition and association.

: :

The disjunctive mode of “The Skaters” aligns with Dorsky’s filmmaking in that the “global” connection between successive sequences or shots is often unclear. Speaking specifically about “The Skaters,” Dorsky himself noted how “there’s a momentary congealing of meaning and then the poem evaporates . . . A gap or open synapse exists within the logical momentum of materials. The way (Ashbery) weaves motifs allows me to think of visualizing things as they might occur in the language of film.”7 Indeed, this “evaporative” quality of Ashbery’s poem is clearly present in Dorsky’s work. His close friend, filmmaker Warren Sonbert, first coined the term “polyvalent montage,” which Dorsky quickly adopted to articulate a shared film editing ideology. The basic formal strategy is one that “organiz[es] the shots and rhythms of a film so that associations will ‘resonate’ . . . several shots later.”8 Shots are sequenced so as to interact not merely with adjacent shots, but also with those that appear much earlier or later in the film—think of Ashbery’s aforementioned use of repetition, and how it creates oblique associations with earlier moments in his poem. Dorsky notes, “I want complex resonances, not simple parallels that can be easily verbalized.”9

Dorsky’s film Hours for Jerome provides a prime example of the function of polyvalent montage. Filmed between 1966 and 1970, Dorsky did not complete the film until 1982, following a period of intense depression and reduced filmmaking activity.10 The completed work is a stunning stream of images, clearly the work of an expert photographer. And since there is no soundtrack, the film relies entirely on those images and their sequencing for its effect. In a contemporaneous review for The Village Voice, J. Hoberman wrote that Hours for Jerome “suffers from the absence of a strong conceptual grid, but the film is so frequently gorgeous that it scarcely matters—you’re content to watch it in an eternal present.”11 Hoberman’s review represents a common response to Dorsky’s films: the beautiful quality of his compositions is undeniable, but the connective logic remains elusive. However, his construction is more precise than a first impression may indicate.

On a granular level, Hours for Jerome is made up of many clustered sequences, which Dorsky has called “stanzas.”12 These sequences are separated by passages of black leader (i.e., imageless black frames), which function interstitially, much like stanza breaks in poetry. Sequences can vary considerably in length, complexity, tone, and formal style: some intercut between numerous different subjects, drawing out rhymes or other subtle connections, while others are more simple landscape meditations taken from a tripod or diaristic, handheld scenes. These are often constructed around an event, or a related idea. For instance, during one section, we see an extended sequence made up of shots taken onboard a riverboat; the montage includes images of other passengers, as well as more abstract appreciations of water, light, and found geometry. This is followed by an interval of black leader, and then another sequence that strings together a handful of shots captured from a poker game, edited together as a series of shot-reverse shots of the players that almost resembles a conventional dramatic scene.

Sequences can also be more mysterious, like that which precedes the riverboat scene: Dorsky crosscuts flickering, verdant nature images with warm interior frames super-imposing shots of his partner Jerome Hiler lounging and patterns from various furniture, as well as a repeated shot of twin shafts of light reflecting across a close-up of a spinning vinyl record. Abstract as this sequence is, it still presents an internal logic: the floral patterns adorning the upholstered furniture ironically harmonize with the various images of real flora; the camera tracing the curved rim of a lampshade matches the shape of the LP disc; additionally, we can notice that Hiler is seen reading a book about Mozart, a further bridge to the spinning record.

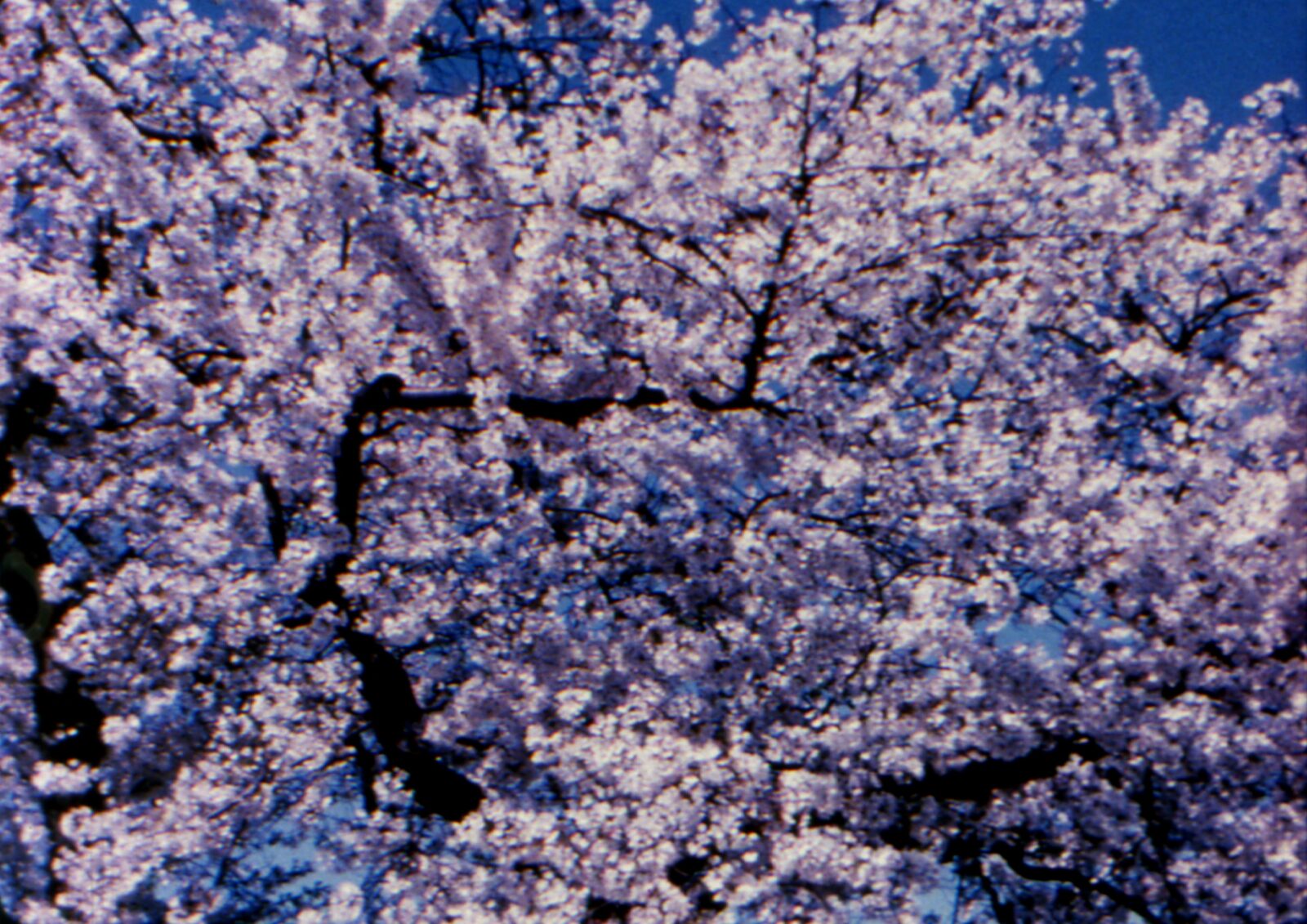

Much like “The Skaters,” the film offers kernels of understanding at a “local” level; however, it refuses to provide any clear “global” meaning for viewers to latch onto—the absent “conceptual grid” that Hoberman laments. Typically, individual sequences, or “stanzas,” are bound by some sort of identifiable logic, but there is an absence of traditional causality linking sequence to sequence. At the highest level, Hours for Jerome is organized by seasons, with spring and then summer imagery making up Part One, and Part Two encompassing autumn and winter. But despite that specific structural principle, the seasonal organization lends only a tenuous framework—it’s not as if Dorsky’s aim is simply to represent the qualities of each of the four seasons. We can understand that we’re watching, say, a section of footage that was entirely captured during the spring, but that only explains so much: we are still left to wonder why these images appear in the particular order and manner in which they do. Dorsky offers one explanation: “Meaning itself was not the goal; the journey itself of going through the images would be the place of the film.”13

Among their many similarities, the shared sense of discordance in these two works is evident in their respective celestial motifs—both repeatedly look to the heavens to enact some kind of (dis)order. In “The Skaters,” the final couplet fails to offer any ordered closure because, despite Ashbery’s assertion that the constellations are rising “in perfect order,” he actually presents them out of their proper astrological order: “…Taurus, Leo, Gemini.” We are left with that contradictory couplet as the poem’s conclusion. Dorsky also uses heavenly bodies as structuring devices: Part One of Hours for Jerome begins and ends with images of the sun and the moon, respectively. However, the latter, lunar shot is disorienting, as silhouetted branches and a flickering exposure effect keep us unsure of what exactly we’re seeing. Only in the final seconds of the shot is it revealed unequivocally to be the rising moon. These celestial objects recur throughout Part Two, but Dorsky’s optical effects and time-lapsed compositions often make it difficult to tell if the orb of light passing between clouds is the sun or the moon—symbols of day and night entangled.

Hours For Jerome’s global opacity can frustrate viewers. Like “The Skaters,” the film initially resists comprehension. But, like Ashbery’s poem, these non sequitur moments can develop significance over time through subtle repetition. Associations are constructed largely in the mind of the reader/viewer, rather than being spelled out clearly by the poem/film. This is the essence of Dorsky’s polyvalent technique: as the film proceeds, new shots recontextualize previous ones, acting not as keys that unlock specific meanings, but as catalysts for mental chain reactions. The seasonal organization ends up playing a role in this function: there is a shot early in the film that shows an exterior sign advertising “Ice Skating”—an activity evidently not currently appropriate given the warming spring climate. This is then picked back up in the film’s final winter quadrant, wherein the landscape has now frozen over and ice skaters fulfill the dangled promise. What began as a dissonance accumulates coherence over the course of the film.

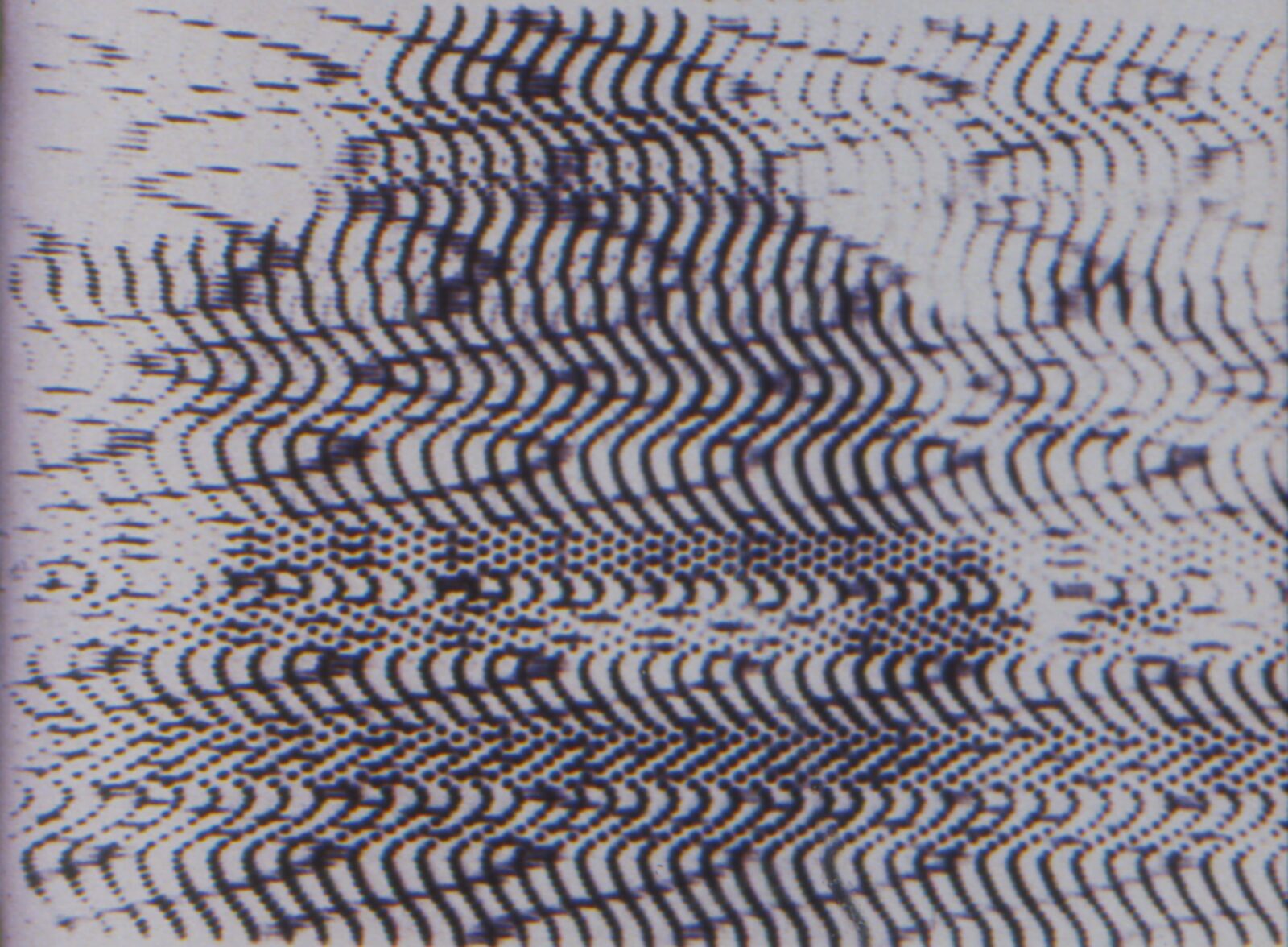

The links formed by Dorsky’s polyvalent montage can be even more abstract, like in the case of a recurring visual pattern: early in the film, we see a sequence including shots of television static, wavering crisscrossed lines that form a shimmering grid. A few minutes later, there is a brief sequence of shots taken beneath an elevated train, with shafts of light filtering down through the metal framework upon the cars and people passing below:

The content of these shots is totally disparate, but there is a clear visual relationship, one that continues to reverberate as this gridded pattern reappears—next as a shot of water passing behind oblong holes in a grate, then later as light diffused through a window screen. Dorsky’s polyvalent technique mitigates the film’s rough edges, softly echoing previous abstractions such that once-confounding features become familiar patterns.

: :

The kinship between Ashbery’s “The Skaters” and Dorsky’s Hours for Jerome is acutely felt in their crafting of disorienting worlds, where spring promises winter, and the month is unsure: “And it is December again, / the snow outside. Or is it June full of sun.”14 However, these disjunctions and disorientations are smoothed out and calibrated through Ashbery’s parataxis and Dorsky’s polyvalent editing. This calibration develops such that connections and resonances solidify beneath the surface, or as Dorsky formulates it: “Ashbery’s ‘The Skaters’ has an atmosphere that continues on beneath.”15 So, as one proceeds through Ashbery’s poem or Dorsky’s film, numerous overlapping chains of associations accumulate, sparking more and more potential “synaptic relationships”16—oblique, interconnected reverberations that may not be “easily verbalized,”17 but, perhaps for that very reason, are all the more strongly felt.

: :

Endnotes

- P. Adams Sitney, The Cinema of Poetry (Oxford University Press, 2014), 9.

- Francisco Algarín Navarro and Carlos Saldaña, Illuminated Hours: The Early Cinema of Nathaniel Dorsky and Jerome Hiller (Asociación Lumière, 2023), 93.

- Scott MacDonald, A Critical Cinema 5: Interviews with Independent Filmmakers (University of California Press, 2006), 94-95.

- Ian Probstein, “Charles Bernstein: Avant-Garde Is a Constant Renewal,” Boundary 2 48, no. 4 (2021): 219.

- Bernstein, Charles. Pitch of Poetry (University of Chicago Press, 2016) 152.

- Brian McHale, “How (Not) to Read Postmodernist Long Poems: The Case of Ashbery’s ‘The Skaters,’” Poetics Today 21, no. 3 (2000): 564.

- Mary Kite, “A Conversation with Nathaniel Dorsky,” Poetry Project Newsletter, February/March 2001, 7.

- P. Adams Sitney, The Cinema of Poetry, 216.

- Scott MacDonald, A Critical Cinema 5, 87.

- Navarro and Saldaña, Illuminated Hours, 17.

- J. Hoberman, “Mute Points,” Village Voice, January 18, 1983, 46.

- Navarro and Saldaña, Illuminated Hours, 93.

- Navarro and Saldaña, Illuminated Hours, 16.

- “‘The Skaters’ by John Ashbery,” Penn Sound, University of Pennsylvania, accessed May 27, 2025.

- Kite, “A Conversation,” 8.

- Scott MacDonald, A Critical Cinema 5, 87. With thanks to Ava Bindas for her writing expertise and meticulous mind.

- Scott MacDonald, A Critical Cinema, 5, 87.