I am a Cancer sun, Sagittarius moon, and Capricorn rising. My Mercury is in Cancer, which means my intellect is emotional and empathetic. I have Leo placements in Venus, Mars, and Jupiter, which indicates an extroverted nature. My Saturn is in Aquarius, which means that I am implacably stubborn; that Saturn is in my first house also means that I have trouble with my self-image. My Uranus and Neptune are in Capricorn and my Pluto is in Scorpio, traits that I share with those born in the first years of the 1990s. Collectively, we are responsible, serious, and hungry for power.

Whether any of this rings true I will leave to my friends and family to decide. I learned these placements and their interpretations through Co–Star, darling astrology app of the terminally online. Billing itself as “the astrology app that deciphers the mystery of human relations through NASA data and biting truth,” Co–Star achieved widespread popularity during the Covid-19 lockdowns, claiming by the summer of 2023 over 30 million registered users. The app’s pleasures are not hard to grasp. Its chic, monochromatic design breaks from astrology’s historic shawl-clad mysticism. Its snarky push notifications ignite a millennial limbic system trained on shitposts. And crucially for this essay, the app surfaces a wide array of astrological data, offering a panoply of potential interpretations of, influences on, and explanations for the daily torment of modern living. These data, Co–Star takes pains to trumpet in its marketing, draw from information collected by NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory at Caltech, alongside the work of human astrologers and poets. All these numerical and textual data enter the black box of artificial intelligence and emerge as horoscopes.

This essay initiates a larger research program on the media history of astrological data. What I pursue here is a reading of how Co–Star mediates astronomical phenomena through technologies of artificial intelligence into the language of its predictions. Doing so entails outlining a provisional scaffolding of astrological media technologies, each level depending in some fashion on the one below it. This scaffolding proceeds as follows: (1) the technical observation of celestial bodies, historically the province of seers, now carried out by governmental and academic institutions; (2) the ordering of such observations into tabular records called “ephemerides”; (3) the drawing of formal horoscope charts based on these ephemerides; and (4) the interpretation of such charts through language. While I’ll touch on each of these layers in turn, my focus is on the final layer, the interpretation through language. I’ll engage a reading of some of my own horoscopes in Co–Star, situating them within traditions of astrological interpretation as well as astrological computing. Through this reading, I’ll argue that Co–Star invokes data to justify astrology as a science, rather than a purely occult practice. This rhetorical move hearkens back to the discipline’s pre-Enlightenment stature, in turn suggesting that the hundreds-year-old rationalist wall barring astrology off from social epistemological legitimacy may indeed be beginning, in the first decades of the twenty-first century, to crack. In particular, I’ll highlight AI as a tool for manufacturing this legitimacy, as both astrology and AI rely on a shared conceptual legerdemain, one that targets an all-too-human logical failing: pattern recognition as a cipher for legitimate intelligence.

The broader goal of this project is to bring my home field of environmental media studies into conversation with emerging work on the cultural study of the occult. Media and the occult are long-standing bedfellows: scholars such as Jeffrey Sconce and John Durham Peters have written at length about connections between the early years of electrified communication and nineteenth-century American spiritualism, for instance.1 Such work has emphasized media’s formal and historical relationships to occult practices, arguing that new media technologies often reproduce or otherwise respond to social desires for supra-human communication, whether over long distances (telegraphy) or with the dead (séances). For my purposes, I am interested in an environmental occult studies for how it enables an inquiry into the changing nature of science (as distinct from occultism) and epistemological legitimacy over time: how practices considered “scientific” in one historical period pass into the realm of the “occult” in the other; how they might pass back; and the role of media technologies in facilitating such shifts. In this way, social practices—divination, magick, communication with the dead, and so forth—don’t simply disappear, discredited, but survive and continue to develop along the parallel track of the “occult,” disreputable to some but meaningful to others. As historian of technology Lorraine Daston notes, inquiries into such occult practices highlight the contingency of modern sciences: “the annals of the history of electricity, phosphorescence, and magnetism are full of results that could not be stabilized by the original experimenter, much less replicated by others,” she writes, requiring an “ambitious naturalizing program” in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries to mark out the appropriate territory for rational inquiry.2 Astrology and astronomy offer a useful case study through which to examine these relationships, sharing, as scholars such as Leona Nikolić have observed, a shared substrate: namely, that of celestial data.3

The measurements of the movements and placements of celestial bodies are some of our species’ earliest data; Assyrian and Babylonian scholars in the second millennium BCE provide the first records of practices both of astronomical measurement and astrological prediction.4 The NASA data upon which Co–Star draws are in many ways still footnotes to this long media history. The horoscope as a popular media genre, by contrast, has a much more recent history, coinciding with the rise of print journalism in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries and its creation of a very contemporary problem: what to fill column inches with? In 1930, the British newspaper Sunday Express launched a trend when they contracted astrologer R.H. Naylor to produce a star chart for the newly born Princess Margaret.5 (Naylor concluded that the princess would lead an “eventful life.”). Co–Star inherits much of Naylor’s newspaper style, albeit with a few novel twists. The app greets users each day with an enigmatic epigram and a short Do/Don’t list. These lists are telling glimpses into contemporary neuroses, tempered by some straightforward mental and physical health recommendations. In my own “Do” lists, I have found: “gut health,” “bubble tea,” “vitamin D,” “expert sources,” and “ellipses.” In “Don’t,” by contrast: “imposter syndrome,” “fake glasses,” “slouching,” “hastiness,” and “locked doors.” Daily reports take up the newsprint style more explicitly:

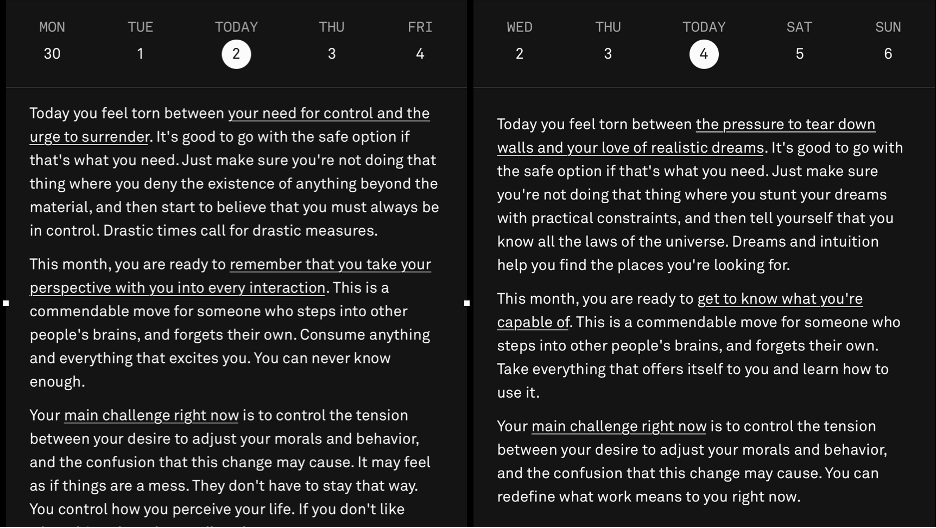

September 1st. Today you feel torn between your need for control and the urge to surrender. It’s good to go with the safe option if that’s what you need. Just make sure you’re not doing that thing where you deny the existence of anything beyond the material, and then convince yourself that you understand everything. Drastic times call for drastic measures.

The app’s tonal register swerves between an internet-informed argot (“just make sure you’re not doing that thing”) and self-consciously poetical spiritualism (“where you deny the existence of anything beyond the material”). These are horoscopes for posting to the grid alongside an artfully chosen Rupi Kaur page. (Upon taking a screenshot, the app pushes a notification reminding you to tag Co–Star in your socials posts.) But more telling patterns emerge over the course of multiple days’ readings:

September 2nd. Today you feel torn between your need for control and the urge to surrender. It’s good to go with the safe option if that’s what you need. Just make sure you’re not doing that thing where you deny the existence of anything beyond the material, and then start to believe that you must always be in control. Drastic times call for drastic measures.

September 4th. Today you feel torn between the pressure to tear down walls and your love of realistic dreams. It’s good to go with the safe option if that’s what you need. Just make sure you’re not doing that thing where you stunt your dreams with practical constraints, and then tell yourself that you know all the laws of the universe. Dreams and intuition help you find the places you’re looking for.

I’ve bolded the sentences that change between these horoscopes; much, one can see, stays structurally the same. Co–Star doesn’t take many pains to hide its use of templates. In a way, they’re a draw. On the one hand, Co–Star wants its users to register a computational substrate to its predictions. A 2019 article from tech outlet The Verge describes Co–Star’s horoscopes as “slightly robotic [and] a little witchy,” reflecting, perhaps, a pre-ChatGPT fascination with algorithmically generated text, before such technologies became associated with the specter of white collar job loss. On the other, more charitable hand, Co–Star as an app emphasizes the stars’ impacts over time: rather than the daily plod of newspaper sun signs, Co–Star teaches its users about astrological transits that unfold over days, weeks, even years. As I checked the app each morning while writing this essay, I began to read the template style as akin to watching clouds drift and shift across the sky, as the stars engage in subtle modifications of my behavior. After all, I don’t change that quickly—why should my horoscope?

Co–Star is far from the first astrology app, or even the first piece of astrology software. By now, it should be clear the immediate applicability of computers to most facets of the astrological data stack: computers can automate the collection of observational data, parse data into ephemerides, and draw horoscope charts from tables. Much of an astrologer’s work is easily automated. The 1970s saw the production of dedicated astrological microcomputers to spare the astrologer the tedious work of calculating time zone offsets and longitudinal variation. Joan Quigley, personal astrologer to Nancy Reagan, famously used one such computer—the Digicomp DR-70—in her work for the Reagan White House. (Presidential scuttlebutt holds that little happened in either the East or West Wings without consulting Quigley, much to the consternation of President Reagan’s more terrestrially minded staff.) Specific astrological software such as Astrolabe, Astrograph, and Astrolog hit the scene in the 1990s, intended for professional astrologers looking to spiff up their business for the information age. Many of these software also assemble computer-generated reports, which, while rudimentary in rhetoric, can span dozens of pages in fine-grained detail.

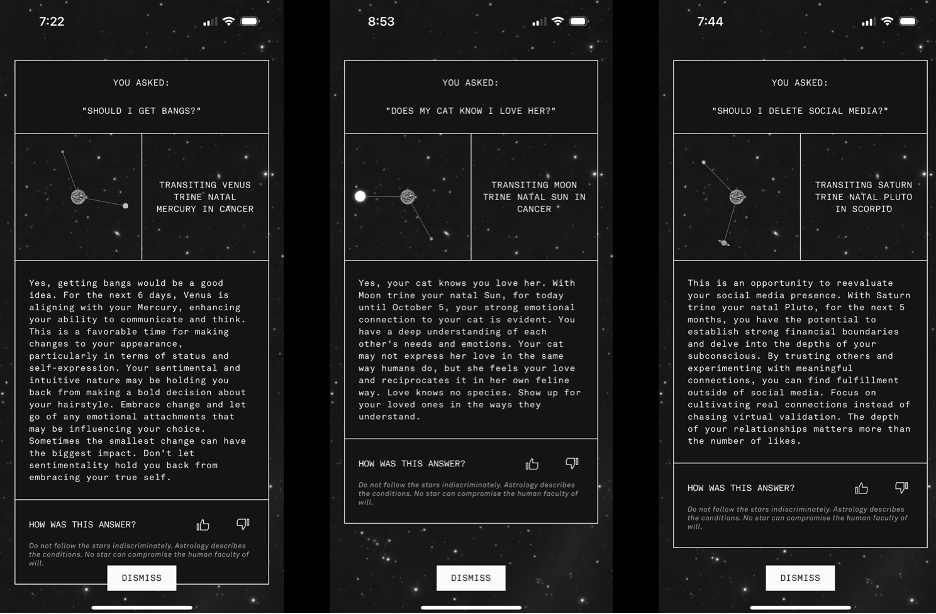

Readers will note that, thus far, we have found nothing in Co–Star’s tech that requires, or even suggests, the use of AI. The templates may be algorithmic, but they are not generative in the sense of large language models. A more recent feature, however, does appear to leverage AI more explicitly: a question-and-answer feature called “The Void.” The Void allows users to submit questions in natural language for astrological consultation, an extension of Co–Star’s stated desire to offer uniquely “personalized” astrology. I dutifully parted with $7 for question credits and consulted the Void on some of the following topics:

Once again, structural patterns emerge. Responses offer an affirmative or negative answer, followed by a time-delimited astrological phenomenon that justifies some psychological aspect. Transits become informatic, evidentiary proof of the readings’ validity. Finances come up a lot. In one of the more telling gestures to the LLM underneath, there are some topics the Void refuses to consider: notably, sex. Questions that cannot resolve into yes/no answers are similarly discarded.

Co–Star launched the Void feature in 2023 with a series of pop-ups in New York City and Los Angeles featuring a large, imposing, vaguely Soviet “computer,” to which users could pose questions and receive printed-out answers on receipt paper. In a profile for the New York Times, Co–Star founder Banu Guler compared the Void device to Zoltar fortune telling machines that once dotted boardwalks up and down the east coast: “Even though you know [the fortune] is garbage,” she says, “it’s special garbage.” I take Guler’s admission not as a gotcha moment, but rather as an indication that Co–Star-the-company is in on the joke, as it were, of Co–Star-the-app. In talking with professional and hobbyist astrologers for this essay, one notable theme emerged: they hated Co–Star. Co–Star isn’t legitimate astrology; it doesn’t provide as much information as competitors; it tinkers with users’ horoscopes in order to emphasize negative aspects; the list goes on. Nevertheless, Co–Star has mastered the need to give readers and users something that seems helpful, even as it might in fact be grounded in nothing at all.

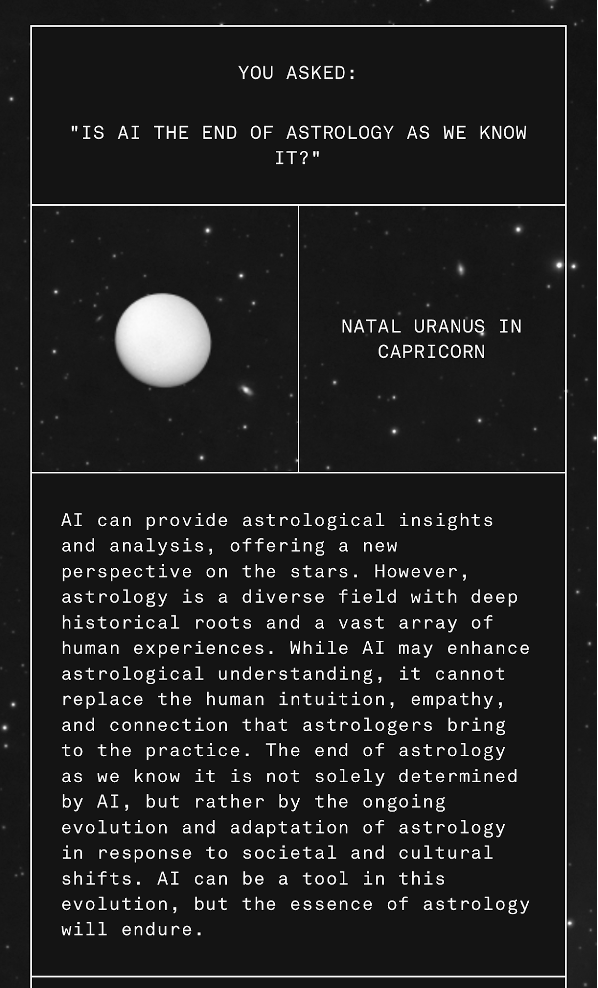

Ironically, Co–Star’s use of AI undercuts its claims on data-driven astrology. Recall that large language models—what we’re talking about when we talk about “AI” in 2025—work by construing statistical relationships between words in corpora of text. Given a natural language input, an LLM will attempt to return the most likely series of words that satisfy a “response” to the input. Any “intelligence” in an LLM is a statistical illusion, a pareidolia: the human psychological tendency towards pattern recognition, even where no such patterns exist. It’s the man in the moon or Jesus in a grilled cheese sandwich. Furthermore, while LLMs are good—quite good—at producing intelligent-seeming text, they often fail at the one thing for which we originally built computers: doing math. By turning to AI, Co–Star maps out a very different future for astrology than the data-driven models of the twentieth century, or even of its own marketing. It doubles down on the illusion. Co–Star doesn’t need AI; Co–Star is AI: the human fantasy that in patterns there is always meaning.

Co–Star, like AI, tries to have it both ways. On the one hand, data-driven, computational, mathematized astrology, just like its software forebears: astrology as a precession of geometric, empirical relations. And on the other hand, poetical, oblique, generically suggestive astrology: astrology as a language game, of polysemous horoscopes that maintain their power (and commercial value) by meaning everything to everyone, and thus nothing at all. Co–Star’s Void feature is, to my mind, most suggestive of the future of astrological data, a natural end to Co–Star’s marketing claims on hyper-personalized astrology. It’s a world where just as we all now have a dutiful secretary named Siri in our pockets, we soon will have our own Joan Quigley. But the addition of AI, in a small but telling way, inverts the chain of causality. No longer do the stars provide the data with which to structure human folly—as above, so below. Now, the messy mix of human language, of likelihoods of words, of things that seem human but aren’t, will guide the stars—as below, so above. Is this really a change? We’ll have to ask the Void and see:

: :

Endnotes

- See Jeffrey Sconce, Haunted Media: Electronic Presence from Telegraphy to Television, Console-Ing Passions (Duke University Press, 2000); John Durham Peters, The Marvelous Clouds: Toward a Philosophy of Elemental Media (University of Chicago Press, 2015).

- Lorraine Daston, “What Can Be a Scientific Object? Reflections on Monsters and Meteors,” Bulletin of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences 52, no. 2 (1998): 49–50.

- Leona Nikolić, “An Astrological Genealogy of Artificial Intelligence: From ‘Pseudo-Sciences’ of Divination to Sciences of Prediction,” European Journal of Cultural Studies 26, no. 2 (2023): 131–46.

- See Liba Taub, Ancient Meteorology (Routledge, 2003), 17.

- Quoted in Linda Rodriguez McRobbie, “How Are Horoscopes Still a Thing?” Smithsonian Magazine (https://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/how-are-horoscopes-still-thing-180957701/, January 2016).