Restless, Zhou San (played by Wang Baoqiang) prepares to leave his home village—a shantytown downstream to the megalopolis of Chongqing—by securing some funds. He casually leaves his gear with a shopkeeper in a subterranean shopping mall, dons a disguise, blends in, and emerges near a bank. Zhou then stalks his prey; he finds a wealthy couple who have just withdrawn money, shoots them, takes his bounty, and heads back underground. He discards his costume, conceals his stash, picks up his gear, and vanishes soundlessly into the bustle of the city.1

What just transpired in Jia Zhangke’s Touch of Sin (2013) is an inversion of what Rebecca Janzen observes in Unlawful Violence, the blatantly doled-out death upon Mexico’s “women, children, or migrants, who live with a high level of socially acceptable violence” and who are seldom noticed2. Zhou San the robber, someone whose socioeconomic status in China is analogous to Mexico’s precariat, reverses this observation by lashing out unlawfully. Jia’s film mediates a terrifying mode of social being; a potent mix of cruelty and violence with an optimism towards the market undergirds all forms of capital accumulation in an economically booming China. Yet a mere five years later, the flighty violence of the lone criminal cedes its quotidian terror to a cold, hard, and technologically mediated reality. In Jia’s 2018 Ash is Purest White, the final departure between ex-lovers and gangsters Tao and Bin (played by Zhao Tao and Liao Fan) takes place in a brisk message exchange on WeChat, accompanied by a blurry image of Bin from an old gambling den’s CCTV footage.3 Thus, while the thrill of Zhou San’s escape into the crowd is still mediated through A Touch of Sin’s martial arts undertones, the digital logic of a budding surveillance regime retroactively transforms these undertones into a mere flight of fancy. Hindsight is 2020: We now understand this shift as an allegory for the tidal wave of digitized biopolitics that the Chinese state unleashed upon its citizenry following COVID-19. A disease born from the reality-shaping powers of capital, COVID-19 ruthlessly drilled past the layers of depravity we once thought to be the nadir of the neoliberal ideologeme of “there is no alternative”; it turns out that neoliberalism’s depravity has much greater depths than we imagined, even if it ironically showed us glimpses of the “nanny state” that it so despised during the pandemic.

Today, a nanny state still couldn’t feel farther away. Despite all the positive developments on the left since the Great Recession, neither the Democratic Socialists of America, Syriza, and Podemos nor France’s New Popular Front have formed their own governments; Palestine isn’t free, and China hasn’t transitioned away from state-led capitalism to socialism either, so it’s safe to say that what Mark Fisher termed “capitalist realism” in 2009 is still firmly here. But how do aesthetic forms entangled with capitalist realism persist, and what strategic openings do they afford us? This short piece re-reads Mark Fisher through Fredric Jameson and Laura Berlant to examine how the idea I term Realism’s Capitalism—the aesthetic corollary, symptom, and solution to capitalist realism—manifests itself in Jia Zhangke’s films and what that means for thinking capitalist realism on a global scale fifteen years after the publication of Fisher’s treatise.

If Mark Fisher’s Capitalist Realism initially described the transatlantic zeitgeist around the 2008 Financial Recession, then following the global left-and-right populist waves of the 2010s, the pandemic, China’s recent economic slowdown, and the sociocultural synchronicity between the U.S. “quiet quitting” and Chinese “laying flat” (tangping) suggest that capitalist realism as a global structure of feelingexists both universally and unevenly. During a boom, there is no need for an alternative; in a bust, one wonders if there truly is no alternative to capitalism. Thus, the “realism” in capitalist realism is also the “realism” of the international relations field, a “deflationary perspective of a depressive who believes that any positive state, any hope, is a dangerous illusion”.4 This idea pertains to China and the Global South, as well. Dai Jinhua’s diagnosis of Zhang Yimou and Jet Li’s 2002 blockbuster Hero as a capitalist-realist film precisely pinpoints how contemporary China infuses a premodern concept like tianxia (all under heaven) with reactionary nationalism and the might of the market; as Dai quips, “[I]f radical social change or revolution is impossible… then the best choice in a choiceless world is to consent or make alliance with power.”5 Submitting to this sense of “being realistic” paradoxically entails, per Fisher, dealing with a system that always demands your malleability, “subordinating oneself to a reality that is infinitely plastic, capable of reconfiguring itself at any moment.”6

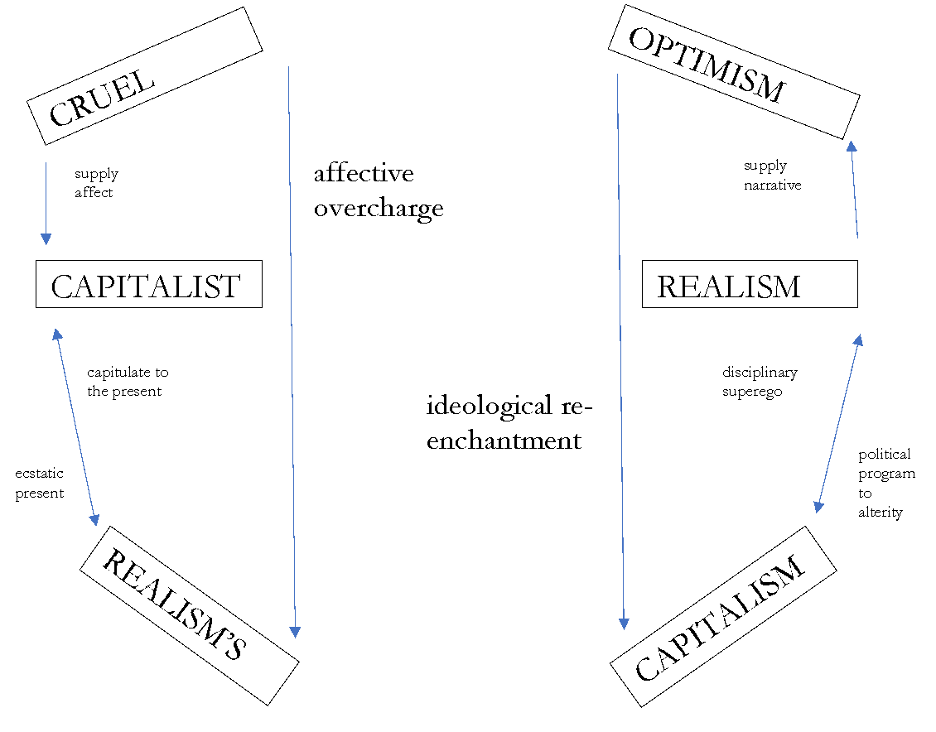

Nonetheless, to quote the famous last words of Fredric Jameson, all these thinkers know intuitively that “the future of “‘the problem’ is the problem of the future,” and in the chiasmus of Capitalist Realism hides its dialectical shadow and bane, Realism’s Capitalism and the aesthetic praxes that comes from capitalist realism but push beyond it.7 In his study on realism, Jameson identified the two major antinomies as the conflict between narrative (storytelling) and affect (scenic description). Constantly engaged in a tug-o-war between narrative and affect, realism consists of a “pure form of storytelling with impulses of scenic elaboration, description, and above all affective investment” where the “scenic present” despises “other temporalities” constituting the force of the narrative.8 Realism is thus torn between an eclipsing, monstrous present and the relentless drive to complete the narration of the tale, the plot, and the diegesis. Mapped onto the lingo of Realism’s Capitalism, affect in the present can embody capitalist realism’s injunction to stay confined within the purely synchronic now or ecstatic moments that allow a glimpse beyond the matrix; the narrative drive can play the role of capitalist realism’s disciplinary superego, and, at the same time, point to the political program that delivers us to different conclusions. When reframed through capitalist realism, Jameson’s antinomic realism becomes the chestburster that is Realism’s Capitalism, an aesthetic practice and economic object that contains the seeds of futurity, despite its own enmeshment within the dogmas of the capitalist present.

Here, I would like to introduce a third term to the schema of capitalist realism and Realism’s Capitalism, which is Lauren Berlant’s concept of cruel optimism: the idea that your suffering doesn’t make you stronger; rather, you desire that which ensures your debilitation. Published two years after Fisher’s work, Berlant’s Cruel Optimism is a complementary period piece dealing with similar subject matter, despite its different focus. Take, for example, how Berlant describes life under neoliberalism: “The conditions of ordinary life in the contemporary world even of relative wealth, as in the United States, are conditions of the attrition or wearing out of the subject, and the irony that the labor of reproducing life… is also the activity of being worn out by it.”9 An incisive diagnostic of the stagnation in the quality of life, income, and one’s social mobility in the Global North, we can readily map Berlant’s observations onto the crises in other developed locales, from China to South Africa, Russia, and beyond. Does it not also illustrate the conditions contributing to the formation of the lying-flat (tangping) in China and Japanese shut-ins (hikkikomori) during an economic recession? In Jamesonian realism, cruel optimism therefore exists as capitalist realism’s affective dimension, and as such, capitalist realism exists as cruel optimism’s narrative dimension. While cruel optimism continues to derail the tendency to resist Realism’s Capitalism vis-à-vis ideological re-enchantment, it also supplies an affective overcharge to Realism’s Capitalism, a charge that fuels self-disclosing discontent towards the present. A very basic Greimas square detailing their relationships would look like this:

Cruel optimism both abets and betrays its twin, capitalist realism. Realism’s Capitalism, with the affective arsenal of cruel optimism, is then forced to disclose an artwork’s resistance towards capitalist-realist narratives and thereby potentiate its negation.

We see this dynamic embodied in the final scene of A Touch of Sin., wherein Zhao Tao’s character, on the lam for murdering two abusive customers at the sauna she worked at, drifts to the north in search of a new beginning. Wandering along the ancient walls of Shanxi province, she comes upon a performance of the Yuan Dynasty play The Injustice of Dou E, the tale of a widow forced into a life of crime due to hardship. The actor playing the judge repeatedly calls to the crowd as the camera closes in on Tao: Do you admit to your crimes? Here, the disciplinary superego of capitalist realism is coupled with the judicial injunction of the play, indicting Tao for transgressing her class status, a status forged by the market and the post-reform Chinese Communist party through ideological re-enchantment. Remember, the party says, there is no alternative to our socialist market economy, and you should be grateful just to have work. This scene symbolically delegitimates Tao’s earlier act of retributive justice, one that brought her into the ecstatic present of Realism’s Capitalism and a state of existential freedom earned through resistance. Facing the accusation, Tao initially appears stoic, but as she eventually starts to wince and crumple under the charge, the camera cuts to the sea of spectators. At first glance, this cut only dilutes Tao’s intense emotions over a mélange of faces, each of them less intentional in their expression, but for the viewer, the crowd’s affect of indifference also creates the effect of obscuring Tao, shielding her in the frame from the hostile gaze of the stage. This shift to the crowd thus simultaneously indicates a broadened accusation of guilt from the voice of capitalist realism and a glaring refusal by the spectator to acquiesce. Moving from a singular, focalized perspective on Tao to the collective gaze of the masses, this effectively overcharged shot therefore overwrites the previous close-up’s injunction for Tao to capitulate to capitalist realism and transforms it into Realism’s Capitalism’s pushback.

The film concludes here. After lingering for a few seconds on the crowd with both the system’s aural indictment and the masses’ visual resistance, we cut directly to the credits, tempting the audience to steer the wheel of this yet-to-be concluded story, to supply the next narrative sequence from the standpoint of Realism’s Capitalism. Will cruel optimism re-capture the future into yet another loop of capitalist realism, or will its affective overcharge be enough to hurtle our Realism towards a political program for a non-capitalist alterity? What Fisher, Jameson, and Berlant’s work ultimately show in tandem is that, less than an aesthetic genre, Realism’s Capitalism is more akin to an aesthetic mode, one that carves its spirals of flight through the dialectical tension between affect and narration. Realism’s Capitalism affirms that realism must constantly negotiate with the capitalist landscape producing it, while accompanying the constellations of past, present, and future class, and of cultural struggles. Realism confronts the affects produced by capitalism’s drives to mystify by producing new desires10, and surely one day, it will pierce the heavenly veils cast by capitalist realism whose power once seemed utterly inescapable.

: :

Endnotes

- A Touch of Sin, directed by Zhangke Jia. Kino Lorber, 2013. Accessed November 28, 2024.

- Rebecca Janzen, Unlawful Violence: Mexican Law and Cultural Production (Vanderbilt University Press, 2022), 4.

- Ash is Purest White, directed by Zhangke Jia. Cohen Film Collection, 2018. Accessed November 28, 2024.

- Mark Fisher, Capitalist Realism: Is There No Alternative? (Zero Books, 2022), 5.

- Dai Jinhua, After the Post-Cold War: The Future of Chinese History, ed. Lisa Rofel. ( Duke University Press, 2018), 54.

- Fisher, Capitalist Realism, 54.

- Fredric Jameson, The Years of Theory: Postwar French Thought to the Present (Verso, 2024), 449.

- Fredric Jameson, The Antinomies of Realism (Verso, 2013), 11.

- Berlant, Cruel Optimism, 28.

- Jacques Lacan, Écrits, trans. Bruce Fink ( Norton, 2006), 724.