In 2022, after using the text-to-image diffusion model, Stable Diffusion 1.5, artist, animator, and podcaster Soda Khan shared four AI-generated images of grimoires.1 The images depict glowing blue and green lights emanating from leather bound books with metallic details and incoherent text. Khan’s generated images are not the only grimoires shared on the Night Café AI Art Generator website, nor are their aesthetics unique. Rather, these AI-generated images echo a longer aesthetic and technological history of the relationship between the occult, algorithms, and digital technologies.

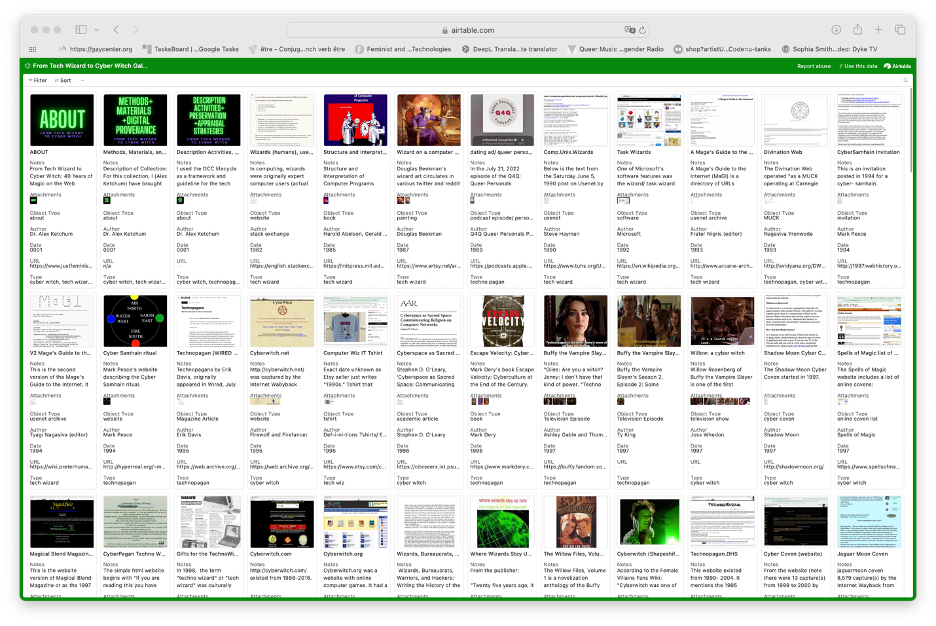

In my digital exhibit, “From Tech Wizard to Cyber Witch: Invocations of Computing Technologies as Magic, 40+ Years of Magic on the Web,” I investigate the different uses of tech terminology and metaphors that rely on ideas of magic, mythmaking, occult, and fairy tale imagery. With over 175 examples, organized chronologically and spanning from 1982 to 2025, the exhibit demonstrates the ways that magic as a metaphor can be used to waive away technical explanations, while communities of witches and techno pagans have simultaneously embraced digital and algorithmic technologies as part of their spiritual practice. As a historian, I have utilized a wide range of sources to better understand this phenomenon. I have tracked references in popular culture and television shows; analyzed cyber spell books; combed through technology magazines, such as the January 1987 issue of Crash via the Computer Magazine Archives on the Internet Archive; used the Internet Wayback Machine to access cyber coven websites created in the 1990s; referenced the 1982 edition of the Hacker’s Dictionary; accessed cyber witch card deck projects; and even tracked the rise of emoji spells in 2016 and Tumblr’s cyber witches.2 While scholars such as Douglas E. Cowan have looked at the relationship between paganism and the Internet through the lens of religious studies, I frame this phenomenon within a technological and labor history.3 Understanding the power of magic as a metaphor for technology continues to be relevant as magical thinking can gloss over how technologies function and can obfuscate potential social and environmental harms in technologies such as AI and machine learning.

Three figures are particularly important for understanding the relationship between magic as metaphor and magic as practice: the “tech wizard,” “cyber witch,” and “techno-pagan.” First, as I have explored elsewhere, terms like “tech wizard,” which originated in hacker and computer cultures in the 1980s, amplify the narrative of the exceptional tech genius.4 Writers and commentators that did not understand how specific computing technologies actually work employed the term as a stand-in for “just like magic,” a phenomenon journalist John Herrman remarked upon when surveying the latest AI technologies marketed in 2023. The terms “techno pagan” and “cyber witch” from the 1990s onward served to present an alternative identity within tech spaces and sometimes paralleled the creation of cyberfeminist communities. Unlike “tech wizard,” the terms “techno pagan” and “cyber witch” were, and continue to be, more often used to self-identify. When the tech wizard entered the mainstream, which he did in everything from computer magazines, newspapers, and television shows, the cyber witch would find herself in online cyber coven meetings and cyber spell books. As an object, the cyber spell book in particular demonstrates the manner in which generative AI relies on this longer history, yet abstracts the labor and community building that made the creation of these books possible.

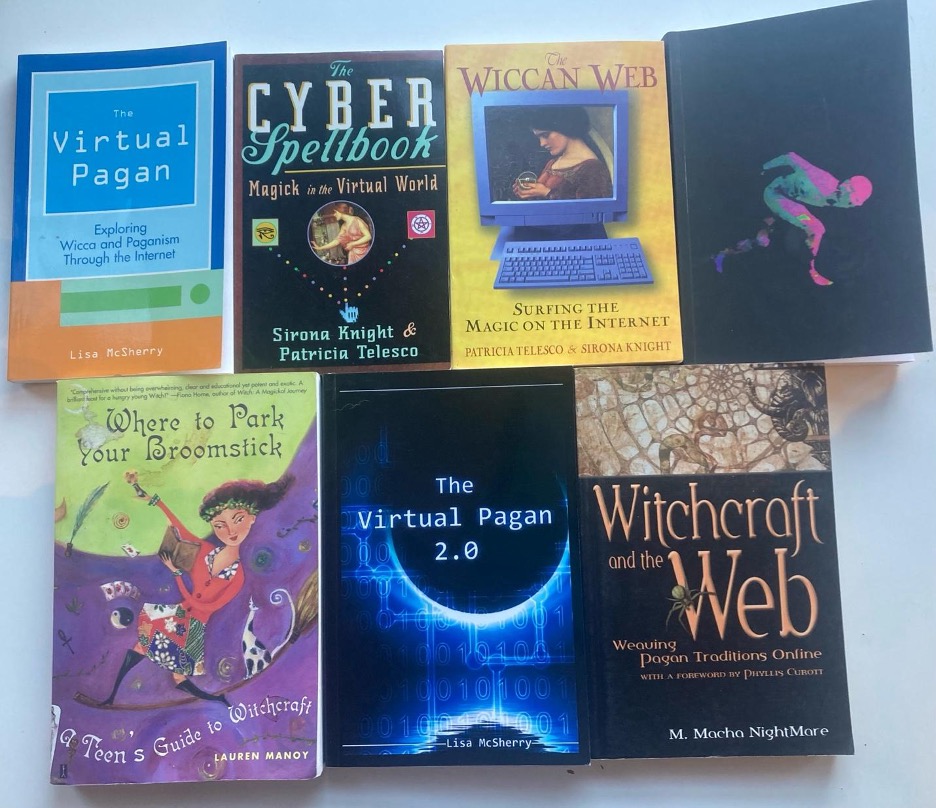

The genre of the cyber spell book has existed since the early 2000s, but has taken on new forms with the rise of generative AI. In 2001, two of the first cyber spell books were published. Patricia Telesco and Sirona Knight, authors of dozens of occult, New Age, and metaphysical books, published The Wiccan Web: Surfing the Magic on the Internet, and neopagan author M. Macha Nightmare published Witchcraft and the Web: Weaving Pagan Traditions Online. Both books focus on the ways that the Internet connects magic practitioners and how Internet technologies can be incorporated into magic rituals, with examples such as using your computer mouse as a wand, or conducting “techno spells” to keep your computer from freezing.

Due to the success of their first cyber spell book, Sirona Knight and Patricia Telesco published The Cyber Spellbook: Magick in the Virtual World in 2002. This book, which argues that “for Cyber Witches, technology offers some interesting magickal twists,” gives practical tips such as how to buy candles on the Internet, how to form a cyber dream catcher with a used computer memory chip, magnet, metallic hoop, and speaker wire, and how to “join an international Pagan chat such as the Pagan International Conferences.”’5 Also in 2002, Lisa McSherry published The Virtual Pagan: Exploring Wicca and Paganism Through the Internet, which dedicated a fourth of the book to explaining how to use a computer and access the Internet before focusing on connecting with cyber communities. Cyber tips even made their way into more general books on witchcraft and paganism during this period: the notorious Where to Park Your Broomstick: A Teen’s Guide to Witchcraft, by Lauren Manoy, has a section about witchcraft on the web, encouraging teenage readers to visit specific sites such as WaningMoon.com.6 Even with an emphasis on the digital world, the spell books still underscored the roots of witchcraft and reiterated the importance of the environment; however, if a witch did not have an herb on hand for a spell, she was encouraged to search for an image file of it online to use in her working.

Websites focused on witchcraft and the web also appeared in popular culture in the 1990s. In the popular television show Buffy the Vampire Slayer’s eighth episode, “I Robot, You Jane,” which aired on April 28, 1997, the cast scans occult texts into the school’s library computer as part of a preservation project. In the early 2000s, the idea of keeping one’s own Book of Shadows, the Wiccan term for the book of magic rituals, “burned on a CD (complete with [an] online manual)” was ubiquitous enough within the cyber witch community that Sirona Knight and Patricia Telesco reference it in their book and provide instructions for creating one for newer computer users.7 Beyond including a record of online cyber spell work on one’s hard drive, Lisa McSherry described how to keep a Book of Shadows online.8

: :

While scanning a particular text in the Buffy episode unleashes a demon into the Internet, wreaking havoc in Sunnydale and threatening world destruction, the process of bringing traditional grimoires online actually happens through real-life digitization efforts, such as Google Books’ project of scanning 25 million books beginning in 2002, and the Internet Archive’s book digitization project, beginning in 2005.9 Today, the text and images from cyber spell books, social media discussions about techno paganism, and forums made available online can be scrapped via web-crawlers and used as training data within large language models and large vision language models, enabling generative AI systems including image generators (such as Midjourney or Stable Diffusion) and large language models (such as GPT-4 or Claude) to have the capacity to produce grimoires. Generative AI has changed the relationship between technology and magic.

When AI technologies have been used to create grimoires, the relationship between magic as metaphor and communities of witchcraft practitioners incorporating technology into their practice transforms. On November 20, 2020, self-described “practicing occultist” Alley Wurds published her AI grimoire GPT-3 Techgnosis; A Chaos Magick Butoh Grimoire. The 198-page text—which, according to Wurds, was “written by treating AI Dungeon GPT-3 as though it were a spirit that I had evoked”—includes a series of workings and rituals, as well as a chaos magick system.10 In addition to using the terms “butoh” (the avant-garde Japanese dance-theatre art form) and “mystery play” as text prompts for GPT-3, Wurds also edited the text, equating this technique to the ongoing convention of occult practitioners directing or influencing how information is communicated. While the sentences are technically English and the book does follow motifs of the genre of cyber spell books and traditional grimoires of the past, in part due to Wurds’s own editing and formatting, this AI-generated text actually demonstrates that generative AI does not work just like magic.

Similar to the grimoire images discussed at the start of this essay shared by Soda Kahn, GPT-3 Techgnosis; A Chaos Magick Butoh Grimoire demonstrates that generative AI is a technology built on large datasets that have extracted human labor and creativity to produce nonsensical text. Whereas the cyber spell books of the early 2000s make clear that cyber witchcraft builds on a long history of practice originating before the rise of digital technologies and that these books frequently underline the importance of connecting to the larger community of practitioners online and offline to maintain good relationships, AI-generated grimoires, which actually do depend on past-human labor, exist in abstracted form. The text within Kahn’s images and Wurds’s grimoire are a distorted visual echo, often unreadable or indiscernible.

As users in a Reddit thread about ChatGPT and chaos magick shared, after initial excitement, the results were often underwhelming, and they were uncomfortable with the environmental and labour impacts of AI—especially its impact on artists. One of the final posters reflected that bringing generative AI into one’s practice: “Seems like a terrible idea. Focus and intent are so important and a cold and soulless algorithm can only approximate the shadow of human will.”11 Generative AI does not merely emulate; rather, it betrays core principles of past magical practices online and away from the keyboard.

The history of cyber spell books shows that technology, witchcraft, and the occult are not inherently at odds. The spell books of the early 2000s demonstrated that practitioners could weave together digital and analog rituals. Yet, these spell books also emphasized the importance on community and history. Furthermore, the texts reflected the Wiccan and Neopagan values of care and respect for the environment. AI generated grimoires are at odds with these values when LLMs use exorbitant amounts of water and energy, having deleterious impacts on the climate.12 Due to these limitations, generative AI is not the magical solution. Computing technologies, algorithms, magic, and the occult can co-exist, but doing so requires that the labor and history of humans is at the forefront and not waived away.

: :

Endnotes

- The text prompts were “leather magic grimoire of spells with magic escaping from the book, old book of magic, Yog-Sothoth, R’lyeh, Shub-Niggurath, wet gloss metal render, photoluminescence reflective spectral colors, award winning photograph, unreal engine, realism.”

- The digital exhibit is my effort to bring together the resources that I have used for my research in order to make these materials available to other people interested in researching this topic. As many of these resources exist on defunct websites, out of print books, and far down search engine list results, this digital collection/exhibit assembles these resources in a way that makes them more accessible for viewers and users.

- Douglas E. Cowan, Cyberhenge: Modern Pagans on the Internet (Routledge, 2005).

- For more on this topic, see Alex Ketchum, “Magical Computing,” Hack Curio, October 15, 2022, https://hackcur.io/magical-computing/.

- Sirona Knight and Patricia Telesco, The Cyber Spellbook: Magick in the Virtual World (New Page Books, 2002), 48, 123, 140.

- Lauren Manoy, Where to Park Your Broomstick: A Teen’s Guide to Witchcraft (Simon and Schuester, 2002), 240.

- Sirona Knight and Patricia Telesco, The Cyber Spellbook: Magick in the Virtual World (New Page Books, 2002), 33, 45-47.

- Lisa McSherry, The Virtual Pagan: Exploring Wicca and Paganism Through the Internet (Weiser Books, 2002), 131-139.

- Jennifer Howard, “ Whatever Happened to Google’s Efforts to Scan Millions of University Library Books,” EdSurge, August 10, 2017, and Internet Archive, “Scanning Services,” accessed February 5, 2025, https://archive.org/scanning.

- Alley Wurds, GPT-3 Techgnosis; A Chaos Magick Butoh Grimoire, (Self-published via Amazon, 2020), 2-3.

- “The Uses of AI in Chaos Magick,” Reddit Thread, 2024.

- See Jessica McLean, “Responsibility, Care and Repair in/of AI: Extinction Threats and More-than-real Worlds,” Philosophy, Theory, Models, Methods and Practice 3, nos. 1–2 (2024): 3–16.