When talking about refugees, asylum seekers, and immigration (especially in situations driven by war, poverty, or climate change), both national and international news will focus on the numbers, lack of proper documentation and social burden such refugees bring to the country they arrive into.1The politicization of the figure of the refugee notwithstanding, reducing people to numbers and only showing the issues they create while trying to escape death is not only an attempt at desensitizing the public, but an attempt at normalizing violence against refugees and rendering them and the reasons for which they had to flee invisible to the larger public. Olivier Kugler’s graphic narrative Escaping Wars and Waves: Encounters with Syrian Refugees intervenes in this representation, relying instead on the tension between the visuals and the narrative in order to refuse such invisibility and the atomization of the refugee into a number. Kugler’s style of depicting past and present through color, shading, and sequential white and black sketching that simultaneously accompany and detract from the main images on the page engages with Mark Fisher’s description of capitalist realism, allowing Kugler to figure affects such as hope. Kugler visualizes hope as a process that leaves contours on pages while hope’s temporality is problematized through depictions of refugee camps. In analyzing Fisher and Kugler together, I argue that the paradoxical nature of hope in such camps sustains a life and a vision of the future. While material conditions are dire and there is no end in sight for the wars, senseless hope fuels the realization of an indefinite postponement.2 I emphasize the aesthetic dimensions this graphic narrative marshals in its attempts to avoid ventriloquizing the refugees.3This essay is interested in thinking alongside Fisher about the idea of hope as a radical gesture while taking into consideration concepts such as fugitivity and their association with forced transnational and transcontinental movements.

Olivier Kugler is a reportage illustrator commissioned by Médicins sans Frontières to “portray Syrian refugees in order to help raise awareness about their situation”4 between 2013 and 2017, especially as they were facing what Fisher calls “unresponsive, impersonal, centreless, abstract and fragmentary”5 national and international systems that cemented them in unlivable places for months and years. Kugler’s interviews with refugees in various camps, from Kos in Greece to Calais in France and to Domiz in Iraqi Kurdistan, challenge the normalization of a wide-spread crisis and show the connection between capitalism, war, and everyday suffering in official and make-shift camps. Visibility, as portrayed by Kugler, is a condition of economic value and is politically determined; the arrival and the processing of living bodies (an inherently violent processes) are the most visible aspects of a refugee crisis, and while refugees wait, their legal and non-legal-yet-not-quite-illegal status become part of a longer and traumatic trajectory of constant escape that does not factor into the public image of the refugee. Kugler, following Joe Sacco’s steps to a certain extent, translates transitions, waiting periods, lost stories, and both new and past belongings through aesthetic means that depart from the tradition of neat, orderly page setting and sequential art.

Wars are catastrophes positioned in far geographical areas by capitalist realism’s modes of representation as a way of normalizing large-scale violence. To follow Fisher, uninterrupted wars describe the conditions of exploitation and resource-driven competition that we all live through as neoliberal discourses fuel the image of the blame-free West and exclusionary politics that scapegoat the refugees. Fisher understands the catastrophe as a continuum whose end can only appear through senseless hope. The adjective senseless indicates a break from common sense and immediate material conditions. At the same time, hope is a form of action, an expectation and belief that recognizes one’s inability to control the present time, which conditions one’s relationship with the future.6 In short, having hope suggests recognizing the present as unbearable.7 Senseless hope comprises despair8 and “surfaces as a deeply uncertain and yet radically open response to a blocked future.”9 Hope contains in itself paradoxes and points to moments of stasis and movement in the dynamic between the refugees and the environment. Thus, wars as incomprehensible catastrophes encompassing both active and non-active national participants define the oscillation between despair, hope, fear, courage, and boldness as they chaotically merge in conditions of fugitivity.

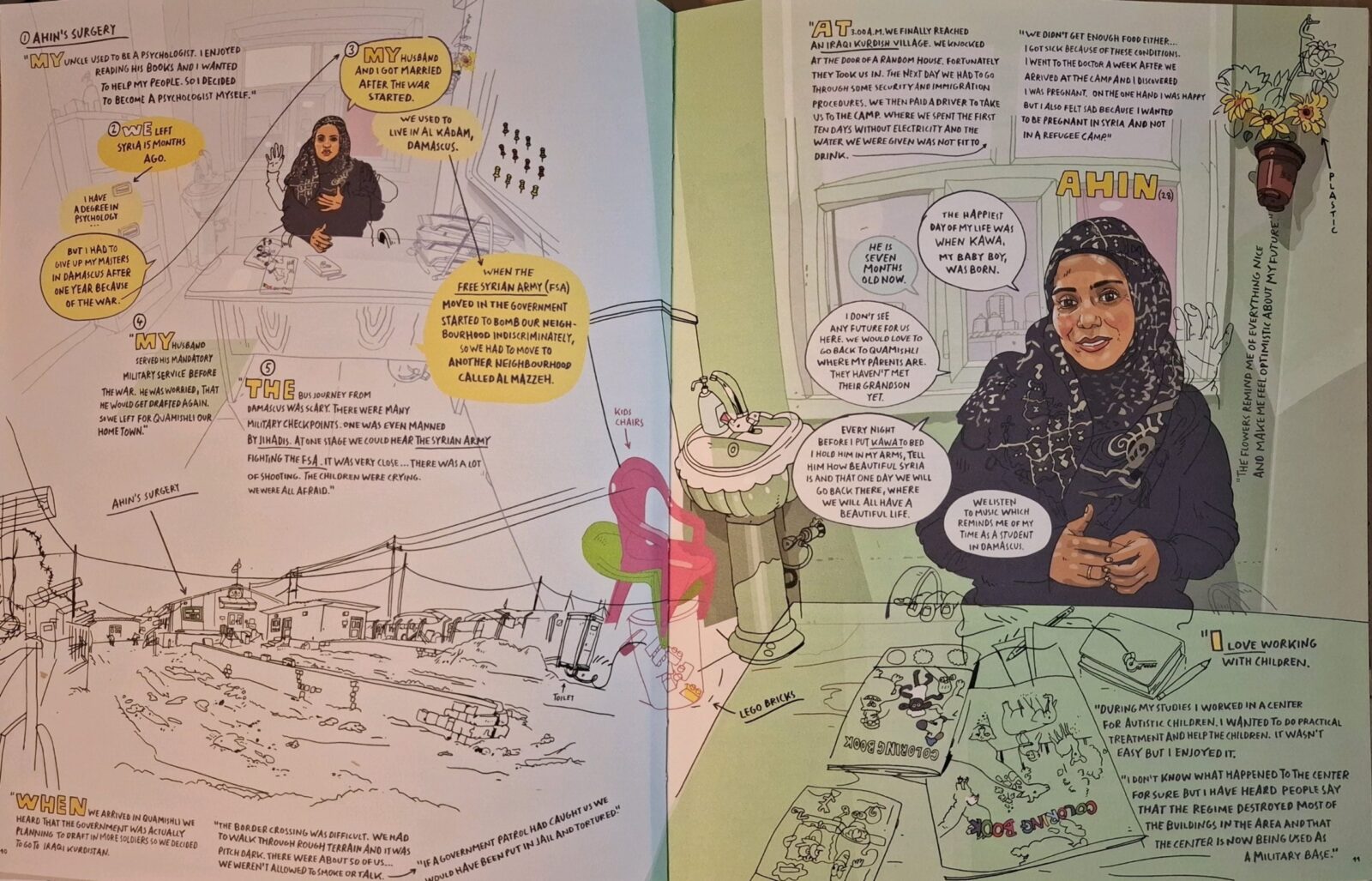

Hope is far from being a completely positive response, as its cruelty in Lauren Berlant’s sense exudes in moments of transition, rejection and waiting. Sherine, a physiotherapist from Aleppo, arrived in Kos with her mother and ill father after a year of many failed attempts at escaping an active conflict zone.

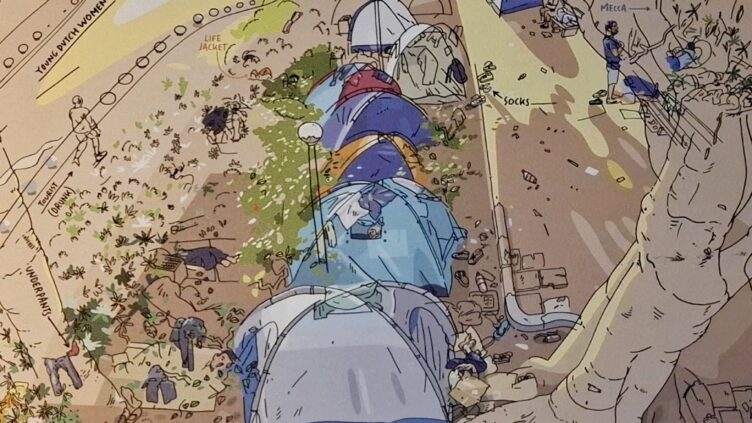

The text on the page does not exactly follow the left to right reading convention but instead helps the reader through the numbering and capitalization of the first word for each instance of Sherine’s testimony. The transparent background, the sketching, and the different layers on this page create, in a way similar to the entire graphic narrative, a disorienting sensation for the reader, in a way mirroring Sherine’s own disorientation as her group walked for hours, took a ferry, and took several buses through Syria, Lebanon, Turkey, and Greece in the hope of reaching Germany. The bodies are pictured at the bottom with the text overwhelming the page, which points to the national and international political narratives effacing the refugees’ bodies, pressing them down into numbers and statistics. The page’s visual dimensions suggest the complex intersection of precarity, fear, and hope while also aesthetically nuancing our way of comprehending fugitivity. Nick J. Sciullo understands “[…] fugitivity as precarity, constant uneasiness, always at risk of trouble or violence […], a material existence rather than the Deleuzian ephemeral transgression. […] The precarity position both pulls from the Deleuzian impulse or movement and the ever-present danger of transgressing [the] law, as well as the status of fugitivity that is always already othered, deferred, and devalued.”10 Sherine mentions her family has money for a hotel room where her father could rest properly, but she can’t access it from their position as refugees who challenge the principle of borders as the extent of state power. It is impossible to not think of Giorgio Agamben’s state of exception, as well as of the homo sacer in relation to the refugees who can be killed with little repercussions since their ontological position resides in a legal and political in-between.11 Sherine and her parents want to arrive in Germany, and despite their year long, arduous journey, the movement created the conditions for hope. But their static depiction on the page, with the father laying down crying, implies despair, a brutal recognition of a blocked future. There is no indication of giving up, despite extreme difficulties, and the juxtaposition of words and images conveys the concomitant existence of anguish and courage.

At the same time, “fugitivity is not only escape, ‘exit’ as Paolo Virno might put it, or ‘exodus’ in the terms offered by Hardt and Negri, fugitivity is being separate from settling.”12 The refugee camp, or the place of arrival, is a transitional, waiting space that can, at best, allow for the creation of different legal statuses, economic conditions, and identitarian re-positioning. It is a place, or, differently put, a non-place, where voices overlap and stories can converge and diverge, all in the hope of getting to a better place that could allow people to return home at an undefined future date. Others, like Ahin, hope to leave the camp in Domiz and directly go back to her hometown.

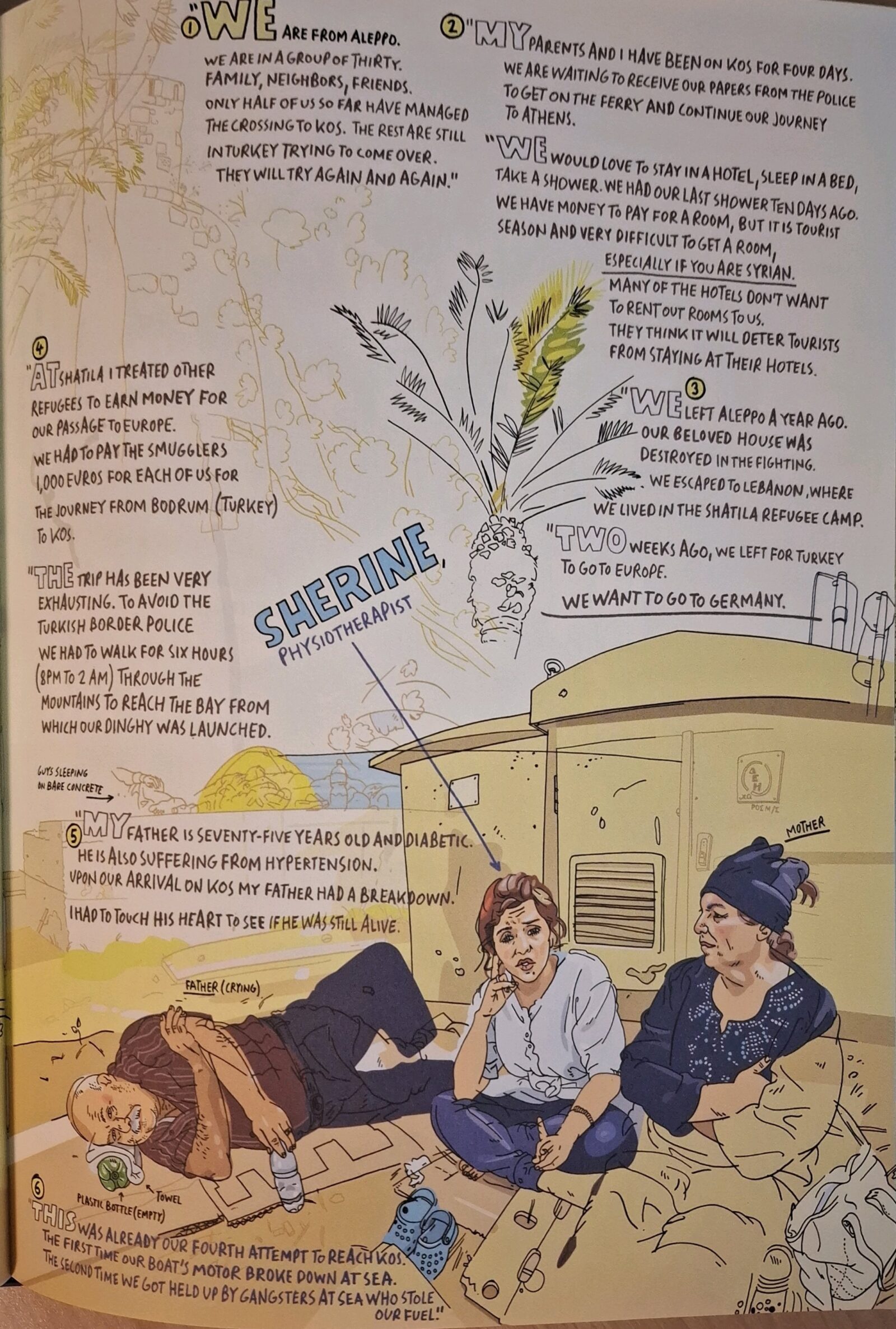

Set in Iraqi Kurdistan, the Domiz camp mostly hosts Syrians who escaped direct bombings in Damascus. Ahin’s story, similar to Sherine’s, does not follow a linear progression: the reading instructions (the numbers in the speech bubbles) suggest a broken rhythm, a fragmented recounting that brings together her education, her marriage, the family’s repeated escapes from the war, and their refuge in Iraqi Kurdistan as the last resort. The inconsistency in the writing pattern and style, from traditional speech bubbles to free text and non-sequitur insertions, emphasize both the fictional aspect of Kugler’s representations of his notes and memories of the camp, as well as Domiz’s reality: a geographical space where stories intertwine to explain the location’s existence.

Furthermore, the drawing, similar to the writing, comes in a few styles in the same spread. Approximate representations of the camps are drawn in black pen while Ahin’s desk is of a lighter shade. Her figure appears in solid colors, almost like watercolors, but there are hands and some other objects revolving around her. Corroborating the text with these visual styles, we realize that it is not just objects that were incidentally present in the tent during the interview, but memories, specifically parts of Ahin’s identity from Syria. She is a psychologist, a well-trained professional, and she gives birth in the camp. While the image’s right-hand side seems to be a magnification of the left-hand side, it actually holds more details, more objects, and a different background as seen through the window. The text presents the reality she is living, but the drawing makes reference to a memory, superimposing two temporalities on the same page. The past and the present cannot allow for settling, with the camp itself making it impossible. However, while Ahin’s story and its visual depiction elucidate the intersection between “escape,” “exit,” “exodus,” and “non settling,” these ideas also propose a more complicated connection between senseless hope and fugitivity when it comes to one’s relation to their own country.

Fleeing from war does not preclude the desire to return to one’s country; it does not describe a continuous movement, but instead a halted state of waiting in an in-between position. The hope to return stops Ahin from attempting to go to a different country, and she tries to remain in the refugee camp until the war ends, a future as elusive as it is violent. Her hope is a type of cruel optimism13, given the aftermath of long-standing war, but her hope also gestures to a survival mechanism, an engagement with temporality that attempts to unblock the future despite a sheer lack of evidence of any possible return. Common sense insists that once the war is over, all the refugees can return home and that there must be a period of peace and support for rebuilding. However, as Fisher describes extractive capitalism, the reality of extremely profitable prolonged proxy wars, environmental destruction as a form of war, and rebuilding as a form of extraction all short-circuit this logic. Fisher’s conceptualization of senseless hope allows us to see Ahin’s determination to return to Damascus as a radical gesture14, for her open response to uncertainty creates space for deciphering a possible future.

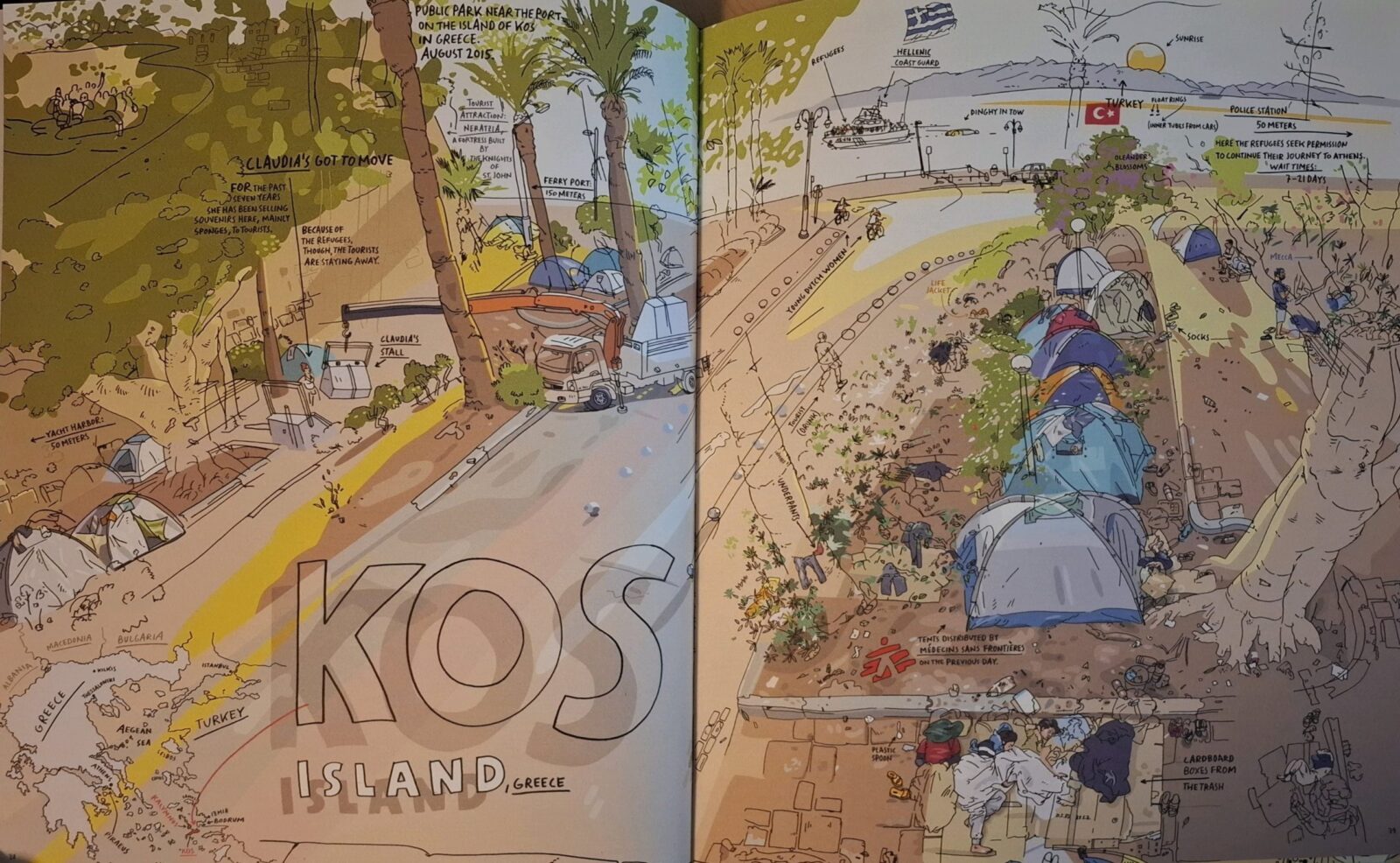

Kugler invites us to think about static moments, to ponder over the almost invisible aspects of waiting. On Kos Island, in Greece, there are very few tents, and the refugees sleep on the street and on cardboard boxes while waiting for their paperwork to be completed. Kugler’s style encompasses the cluttering of stories, writing that goes in all directions, a cacophony of drawings. The text becomes proof of the overwhelming complexity of visible and invisible factors that created and maintain the current status quo. The differently colored text assumes a pedagogical value in directing the eye, but in the absence of the gutter, the stories float on the page, and the voices dissipate in thin air. The page itself has a metonymic function in relation to the refugees’ situation and the Greek authorities’ lack of preparedness. The lines’ instability, their fading and their interactions with the text, insinuate the ontological precariousness of the refugees’ condition, the almost disappearance of their former status, education, and authority, and of their abandonment in the scorching sun for days on end. On Kos Island, the refugees are not acknowledged as people and their presence does not incite immediate paperwork processing, the allowance of a tent, or even a meal, but these refugees must face a new challenge in order for them to be able to continue their fleeing from the war in Syria. The state, unresponsive and impersonal, signals its presence here by stalling people’s transit and leaving no space for believing in a better future. Static refugees can be invisible while cross border movement presupposes Greece’s approval, in this case, of the current state of affairs and of the refugees’ passing into another country. The stasis has a temporality of its own, an indeterminacy, that demands a particular strength to mourn the losses and to protect one’s hopes of rebuilding what has been destroyed. Kugler’s style embraces formal ambivalence that enables him to negotiate his own authorial identity from a witness’ position. Coming from France and employed by a multinational, a priori impartial organization, Kugler does not discuss the potentiality of realizing the interviewees’ hopes but translates them onto text and image. He becomes a translator in his own right, one who memorializes Ahin’s, Sherine’s and others’ struggles to be visible when all forces attempt to efface their lives. In this graphic narrative, the refugee camps are cacophonous non-places invested with political interests; they are spaces in which hope only exists in its senseless form, full of paradoxes and ambiguities that acknowledge the present and try to unblock the future for a more bearable existence.

: :

Endnotes

- Serena Parekh, No Refuge: Ethics and the Global Refugee Crisis (New York, 2020; online, Oxford Academic, 22 Oct. 2020), https://doi.org/10.1093/oso/9780197507995.001.0001.

- Mark Fisher, Capitalist Realism: Is There No Alternative? (Washington: Zero Books, 2022), 3-21.

- Nina Mickwitz, “Up Close and Personal. Mediated Testimony and Narrative Tropes in Refugee Comics,” eds. Evyn Lê Espiritu Gandhi and Vinh Nguyen, The Routledge Handbook of Refugee Narratives. (Oxford: Taylor & Francis Group, 2023). Accessed December 1, 2024. ProQuest Ebook Central.

- Olivier Kugler, Escaping Wars and Waves: Encounters with Syrian Refugees (University Park, PA: Graphic Mundi, an imprint of the Pennsylvania State University Press, 2023), 3

- Mark Fisher, Capitalist Realism: Is There No Alternative? (Washington: Zero Books, 2022), 64

- Stan van Hooft, Hope (Routledge, 2014), 8

- Jack M. C. Kwong “What Is Hope?” European Journal of Philosophy 27, no. 1 (2019): 243–54.

- Cheryl Mattingly, The Paradox of Hope: Journeys Through a Clinical Borderland (University of California Press, 2010), 3.

- Hirokazu Miyazaki, The Economy of Hope: An Introduction, eds. Hirokazu Miyazaki and Richard Swedberg (University of Pennsylvania Press, 2017), 29.

- Nick J. Sciullo, “Boston King’s Fugitive Passing: Fred Moten, Saidiya Hartman, and Tina Campt’s Rhetoric of Resistance,” Rhizomes: Cultural Studies in Emerging Knowledge, no. 35, 2019.

- Giorgio Agamben, State of Exception, transl. Kevin Attell. (The University of Chicago Press, 2005).

- Nick J. Sciullo, “Boston King’s Fugitive Passing: Fred Moten, Saidiya Hartman, and Tina Campt’s Rhetoric of Resistance.” Rhizomes: Cultural Studies in Emerging Knowledge, no. 35, 2019

- Lauren Gail Berlant, Cruel Optimism (Duke University Press, 2011).

- Jonathan Lear. Radical Hope: Ethics in the Face of Cultural Devastation. (University of Chicago Press, 2006), 103.