Portuguese painter Paula Rego (1935–2022) is often called a remarkable storyteller, as her work is deeply ingrained with narrative.1 Her stories are sometimes personal, entangled with family and childhood memories, individual politics, experiences, feelings, and emotions. But they are also revisions and interpretations of written, oral, or visual stories, as in her series on Nursery Rhymes (late 1980s–mid-1990s), Celestina’s House (2000–2001), or The Shakespeare Room (2005), among many others. Or sometimes they are stories drawn from collective memory, a cultural and political background that forms the history and idea of a nation, as in Salazar Vomiting the Homeland (1960) or When We Had a House in the Country (1962), which delve into the Portuguese dictatorship and colonialism. Or they are affective tales that reveal a space of shared experiences for women of so many different and often impossible-to-concatenate backgrounds. In fact, many of Rego’s paintings participate in all of these categories simultaneously.

This is especially true of the pastel series and related etchings Rego produced between 1998 and 1999 in response to the referendum to legalize abortion in Portugal in 1998. A savage campaign, for and against the decriminalization of abortion, had torn Portuguese society apart. By very thin margins of 50.91% to 49.09%, the referendum failed (the abstention rate was 60%). Angry with the result, Rego reacted through painting, for, as she said, “all I can do is paint; it is the only power I have.” And paint she did, in a brutal and visceral way, to respond to the also brutal political enforcements on women and abortion in the country.

It was only much later, on April 17, 2007, that the Portuguese Parliament approved the law that states that voluntary interruption of pregnancy is not an illegal act. The movements in support of the right to both birth control and abortion started in Portugal in the 1960s, prior to the Carnation Revolution in April 1974 which ended the fascist dictatorship that had ruled the country for 48 years. The long road to the decriminalization of abortion in Portugal started with providing access to family planning, which only became a right after the Revolution with the 1976 Constitution article 67º. By then, thousands of illegal abortions in Portugal were being carried per year, and many women faced severe consequences. As an example, in 1979, Conceição Massano, a young 22-year-old nursing student, was put on trial for having had an abortion following an anonymous report by someone who had found her diary, in which she wrote about her abortion at age 18. In 1990, following an inquiry launched by the police, the Institute of Forensic Medicine examined hundreds of women accused of having had clandestine abortions. The action started after the seizure of the diary of a midwife in Lisbon, with the names of 1,200 women. And as late as 2004, a young 17-year-old went to trial in the Lisbon area after being accused by a male nurse from the hospital and interrogated by the police while still at the hospital. There was a fine line between private and public affairs, especially where women were concerned, a historical continuum that Paula Rego never stopped facing in her work.

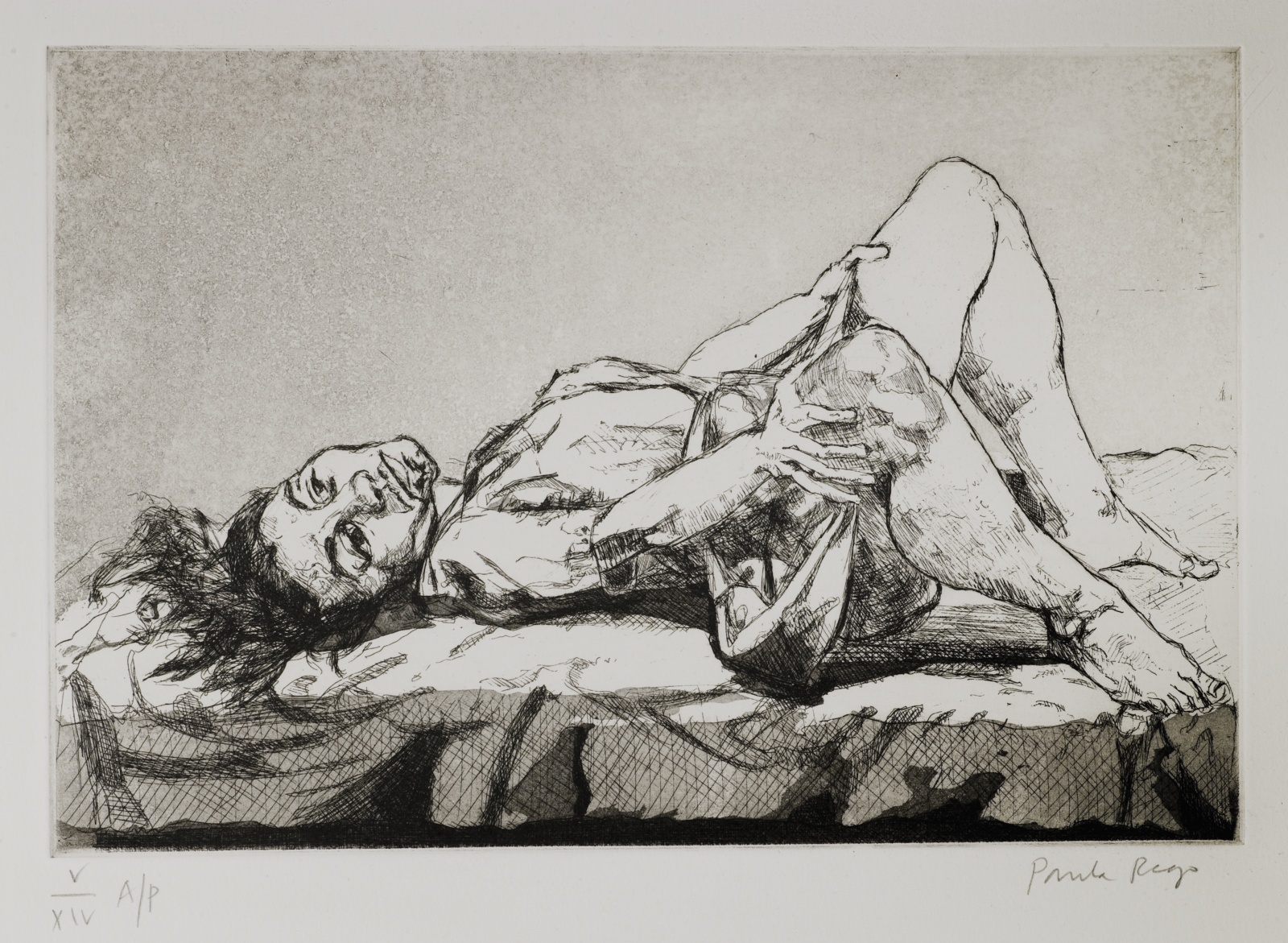

In the 2016 film Secrets and Stories, director Nick Willing presents an engaging and touching portrait of his mother Rego’s life, work, and battles. With her candid and sometimes unsettling testimonies, as if she were in a private conversation with her son, Rego gives us not just a novel insight into her work but also a path to navigate among its many complexities: “I had many abortions . . . In those days, we didn’t have much contraception, and men just didn’t care.” Her personal experience thus narrated, along with her concern for women from the lower classes in Portugal who had undergone backstreet abortions in unimaginable conditions using items such as coat hangers or parsley stems, is at the centre of her 1998 pastel series on abortion. Although all of her other works have title that are an integral part of the work, Rego called this series “Untitled,” which seems to fit the pastel paintings’ theme: numbered one to ten and ending in a tryptic shown for the first time at Calouste Gulbenkian Foundation in Lisbon in 1999. Besides the large-scale pastel on paper paintings, the series includes several drawings and etchings designed to reach a wider audience as they are easier to circulate worldwide than the paintings, suggesting that Rego sought widespread distribution of these images in particular due to her clear political and social purposes.

As T. G. Rosenthal states, “by making these overpowering images available to more people on more walls in more private houses and institutions she was spreading her message far more widely.”2 Even though her graphic work is prolific, Rego sought distribution of “Untitled” not just because of her political agenda, but also as a form of contesting the secluded, hidden, and often too secretive affair of having an abortion. By showing it, the culture of whistleblowing that brought so many women to trial was shattered and made inoperative.

Interestingly enough, the pastel paintings and the etchings seem to visually instigate such a dichotomy: in the pastel tryptic that was shown in the public space of the museum, the women gaze defiantly at the viewer, asserting and standing for their rights with a gaze of accusation: how dare you call me a criminal? they might be asking. In the etchings, on the other hand, the women assume a more subtle stance, looking inwards. If the paintings are metonymically taking the viewer as a whole (society), the etchings seem to be appealing to the viewer’s individual empathy, levelling the ground between all sorts of women and suffering, no matter their differences (age, social status, etc.).

Although she engaged with politics and religion more broadly, Rego insists that “[the main theme of my work] is, especially, abortion. Because abortion existed a lot, every day, several times a day, it was forbidden and easy to get. It was also forbidden in England, but they legalized it much earlier. Not in Portugal. It was hypocritical. Women suffered and died. They threw their bodies into the sea that washed up on the beach later swollen like cows,” she said in an interview.3 In Willing’s documentary, Paula Rego talks about this once again: a fisherman’s girlfriend had an abortion there on the beach by the fisherman himself. She died, her body thrown to the sea, and then washed up on the shore—“swollen like a cow,” she said, to which Nick Willing replied, “So, he killed her then?” “Yes,” she asserted. One never truly knows how much reality there is in Rego’s stories (Nick Willing himself said in an interview that his mother didn’t tell stories “in a classic way”). This was one of the main strengths in her works: continuous acts of transgression, of being on the other side of a deeply patriarchal culture.

Especially during the decades of Estado Novo (not ending with the reinstatement of democracy in 1974), Portugal was an impoverished country, isolated from the rest of the world, focusing primarily on its African colonies (“proudly alone” as António de Oliveira Salazar, the dictator, said). Quite significantly, the ideological basis of the regime was the triad God, Country, and Family—which is to say, religion, nationalism, and a family ideal based on the supremacy of the man and on the submission of the woman. As an upper-class woman, Rego felt these constraints. Still, she never lost sight of how much more difficult life was for women of the lower classes (with whom Rego had close contact in Estoril and, especially, Ericeira, a small seaside village where she spent some years with her grandparents while growing up and where she lived with husband Vic Willing and their three children in the 1960s; these women and their stories and way of living formed a significant trope in Rego’s work and imagery, and she even reported many would ask her for financial support for getting abortions). Paula Rego who, at the age of 16, went to England,4 knew all too well the consequences of the fascist regime and how they lingered far beyond 1974. The silencing, the censorship, the poverty, the widespread influence of Catholic church in society and politics (as was profoundly demonstrated in the case of the abortion legislative process): they all became a part of the Portuguese way of being.

In the book Paula Rego’s Map of Memory, Maria Manuel Lisboa makes an interesting observation: “One of the paradoxes of Paula Rego’s work . . . is that her confrontation with the patriarchal, clerical, and political interests of pre-democracy in Portugal became more intense in the decades following the advent of democracy in 1974; a time when historically, though not, it would seem, for the artist, the spectre of dictatorship in Portugal had been laid to rest.”5 This is particularly poignant because, even though the regime was over, its effects in Portuguese society still lingered inconspicuously, something Rego was very astute to perceive and to put into her paintings. The way Portuguese society dealt with the issue of abortion, and with women in general, was one of those lingering aspects. The way women were treated as second-class citizens, their rights denied, their individuality stifled, their intimacy laid bare, did not end when the dictatorship ended. Rego’s works are swollen with the fear that remained: on the one hand, the fear of feminine power (women have the power to destroy, Rego recognizes, and that is why they are feared6), but also women’s fear of their own power, the fear of the consequences that moving beyond and against patriarchal structures may bring. But even though it is true and quite relevant that Rego departs from the specific Portuguese context (in the case of the abortion series and in many other works), it is no less true that her imagery also deeply conveys universal feelings, particularly in terms of what women are concerned about: pain and fear but also strength, resilience, and combativeness. In the Abortion series’ imagery, the body is indeed a battleground, a fact emphasized by the material particularities of both pastel and etchings: the lines that mark both canvas and paper come to the viewer as metaphoric incisions that the struggles of women’s bodies have been enduring.

Fast forward to 1998. In the mid-1990s, with the series Dog Women, Rego’s figurative style of painting changed dramatically via a change of techniques. Having given up acrylic in favour of pastel, Rego embraced a much more physical and close-to-the-canvas artistic process: “It is complicated, but it is [about] the scratching of the canvas, the scratching of the surface with an object that offers resistance instead of a brush, which is very subtle,” she told me in an interview back in 2005. These paintings also focused more on individual characters than the previously overpopulated depictions and enactments. Instead, she gave us individuals with the energy, stories, and emotions of single bodies—primarily women’s—to which we could deeply relate. This change of setting favoured the intensity of the abortion series and its political potential. Each woman on canvas could simultaneously be all women in the world as well as every single woman. The whole and the particular, the collective and the individual, co-exist in these enclosed spaces with the loneliness, the pain, and the danger inherent to abortion. Going way beyond the particularities of the Portuguese context, these pictures let us know what was happening in secret, even though the focal point is never the act in itself—we see virtually nothing of an abortion taking place, no foetus, barely any blood. But the facial expressions, the positions of the body and legs, the woman sitting on the bucket, the enclosed and even claustrophobic spaces in which the figures are placed: all allude to the seclusion of the act and to its painful consequences. If one of Rego’s stories is straightforward and clear, it is this one: they are not victims but triumphant.

This work is funded by national funds through FCT – Fundação para a Ciência e a Tecnologia, I.P., under project UID/00305/2025 and individual project: 10.54499/2021.00235.CEECIND/CP1664/CT0029.

: :

Endnotes

- Ana Gabriela Macedo, Paula Rego e o poder da visão. A minha pintura é como uma história interior (Cotovia, 2010), 18.

- T.G. Rosenthal, Paula Rego, The Complete Graphic Work (Thames & Hudson, 2003), 149.

- Anabela Mota Ribeiro, Paula Rego por Paula Rego (Temas e Debates, 2016), 145.

- By then, her liberal and anti-fascist father said to her, “This is no place for women, this country. You go away now.” John McEwen, Paula Rego (London: Phaidon, 1997), 44.

- Maria Manuel Lisboa, Paula Rego’s Map of Memory. National and Sexual Politics (Routledge, 2003), 15.

- Maggie McGee, Compreender Paula Rego. 25 Perspectivas, edited by Ruth Rosengarten Ruth (Público/Serralves, 2005), 102.