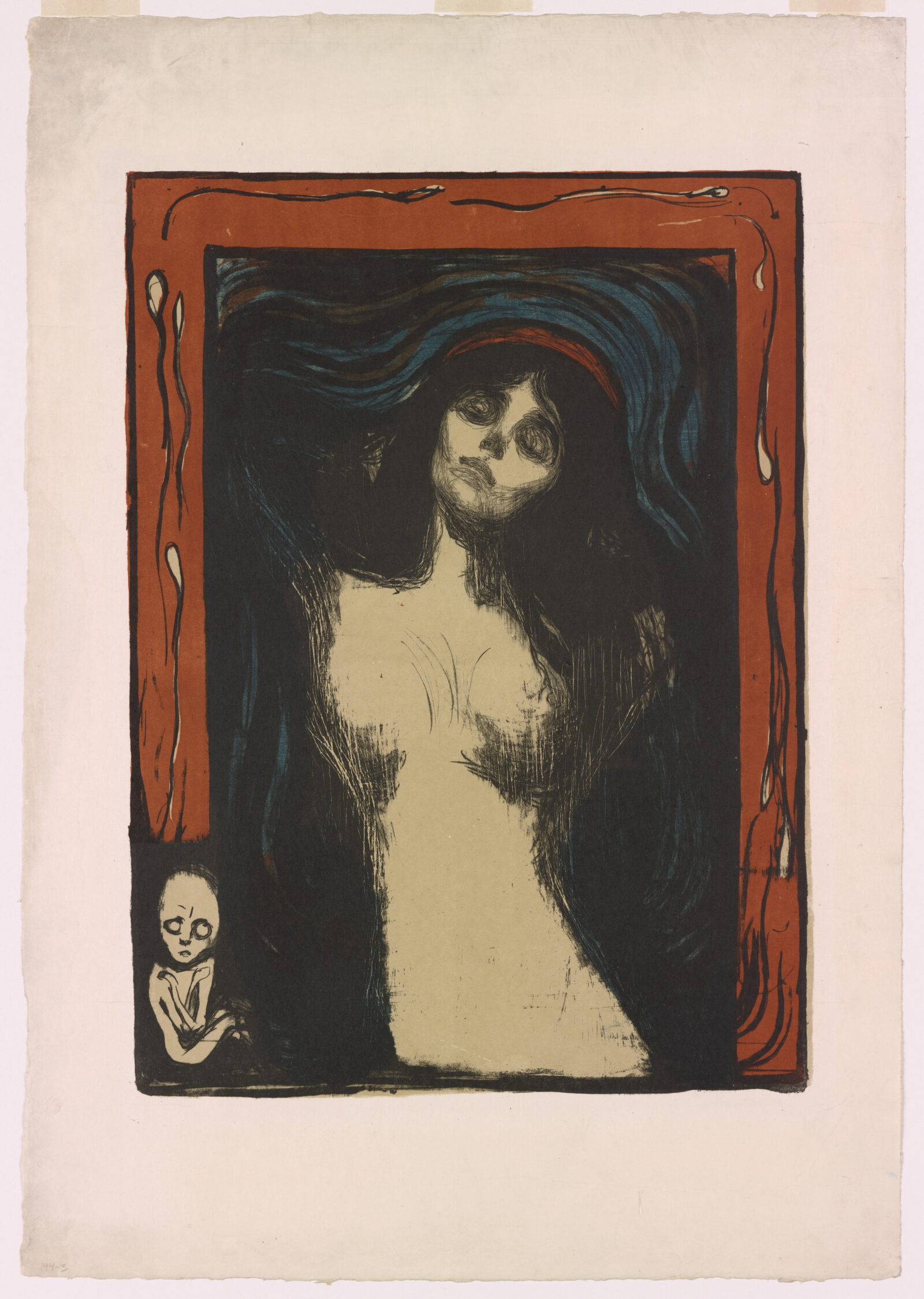

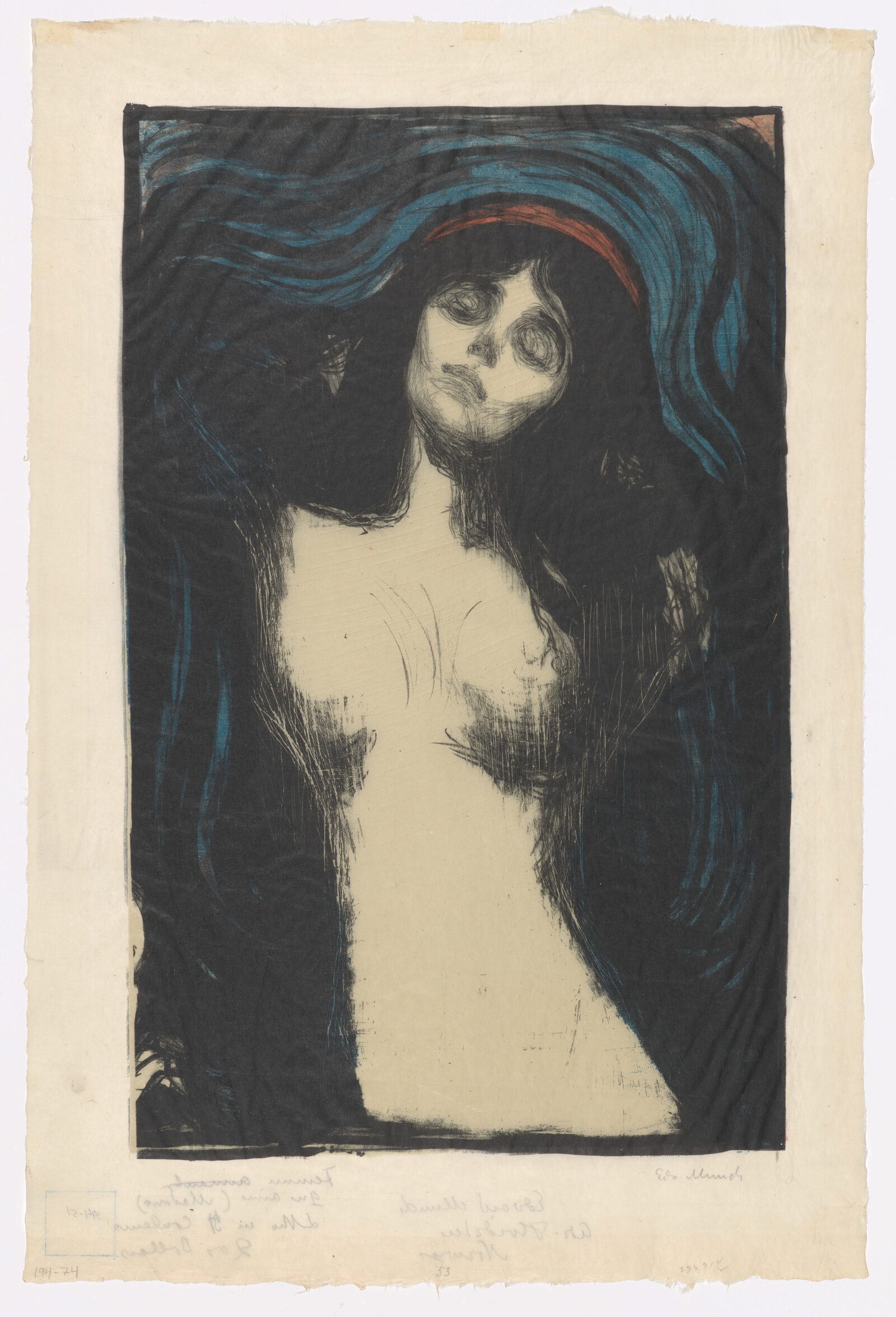

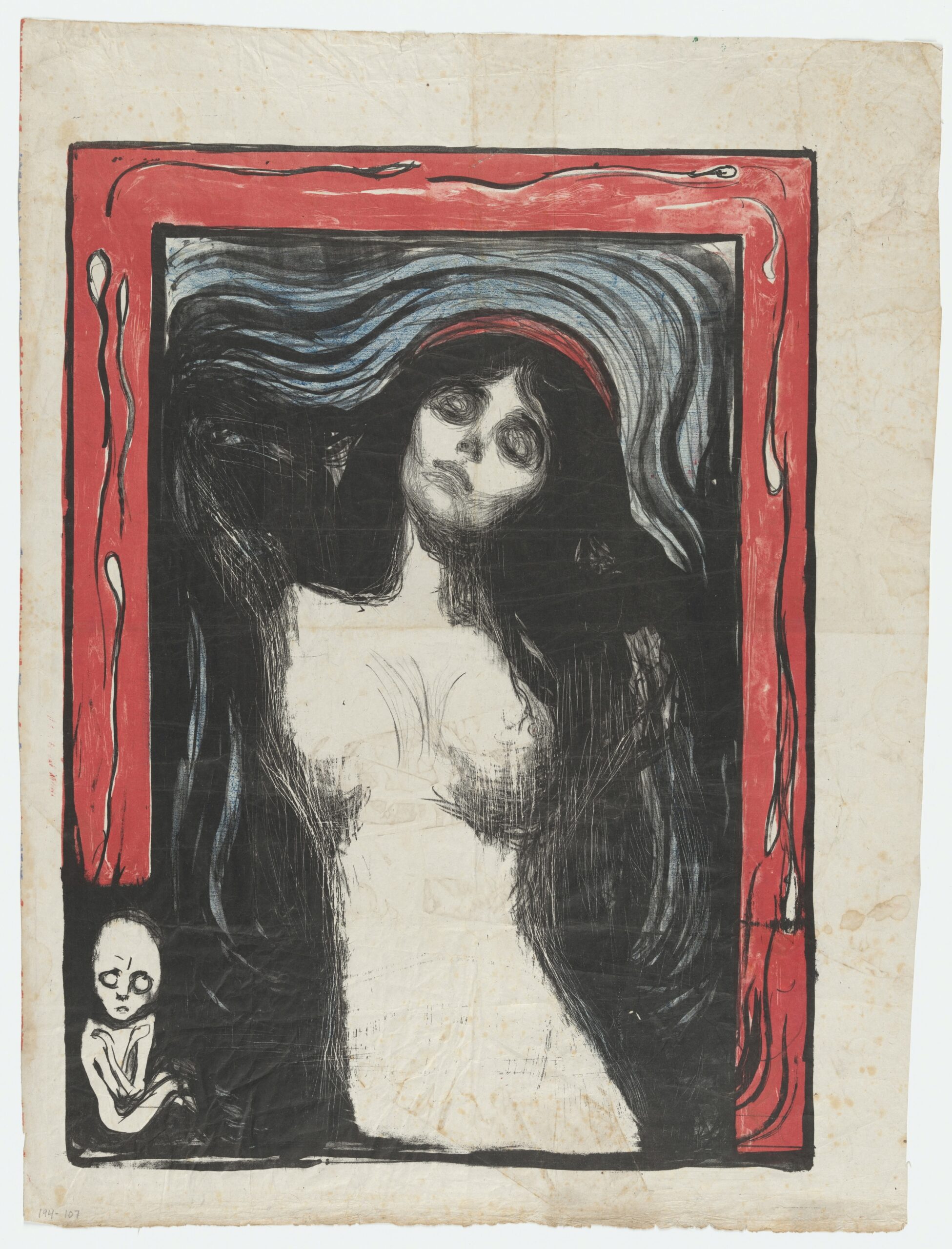

Madonna (1895/1902), one of Edvard Munch’s most famous and heavily reproduced works, depicts a nude woman surrounded by a distinctive red border with spermatozoa and a worried looking infant or fetus in the lower lefthand corner (Figure 1). In 1913, the Norwegian artist exhibited the print at the Armory Show in New York. But he sent an impression without the border, thereby excising the work’s explicit connection with reproductive sex (Figure 2).1 In adjusting the image, perhaps even censoring it, Munch implied a difference between his United States-based audience and the public he was then cultivating in Europe. Madonna is typically read as a universal “Woman,” evoking the putatively common human joys, ecstasies, dangers, and tragedies of sex and reproduction. But Munch’s selection of impression for the Armory show suggests that the work could also be highly topical, implicated and even intervening—or not—in debates over abortion, contraception, and women’s rights in Europe and the U.S. around 1900 and beyond.2

Here, I explore two related moments in the “life” of Madonna: first, a period around its heaviest reproduction in 1902, early in the struggle for reproductive rights, including the right to abortion, in Norway; second, the U.S. around 1990, when the lithograph, border intact, inaugurated a major gift of Munch’s works to the National Gallery of Art from donors with deep and longstanding commitments to the “Great Cause,” the birth control movement as initiated in the U.S. At both moments, the complex and ambiguous connections between reproductive rights and eugenics are evident; contraception, sterilization, and abortion promised freedom for some and coercion and control for others. Attending to Munch’s work, including its critical reception, demonstrates these same ambiguities, revealing how a rhetorics of universality surrounding the artist and the print could feed a white savior discourse of birth control as population control.

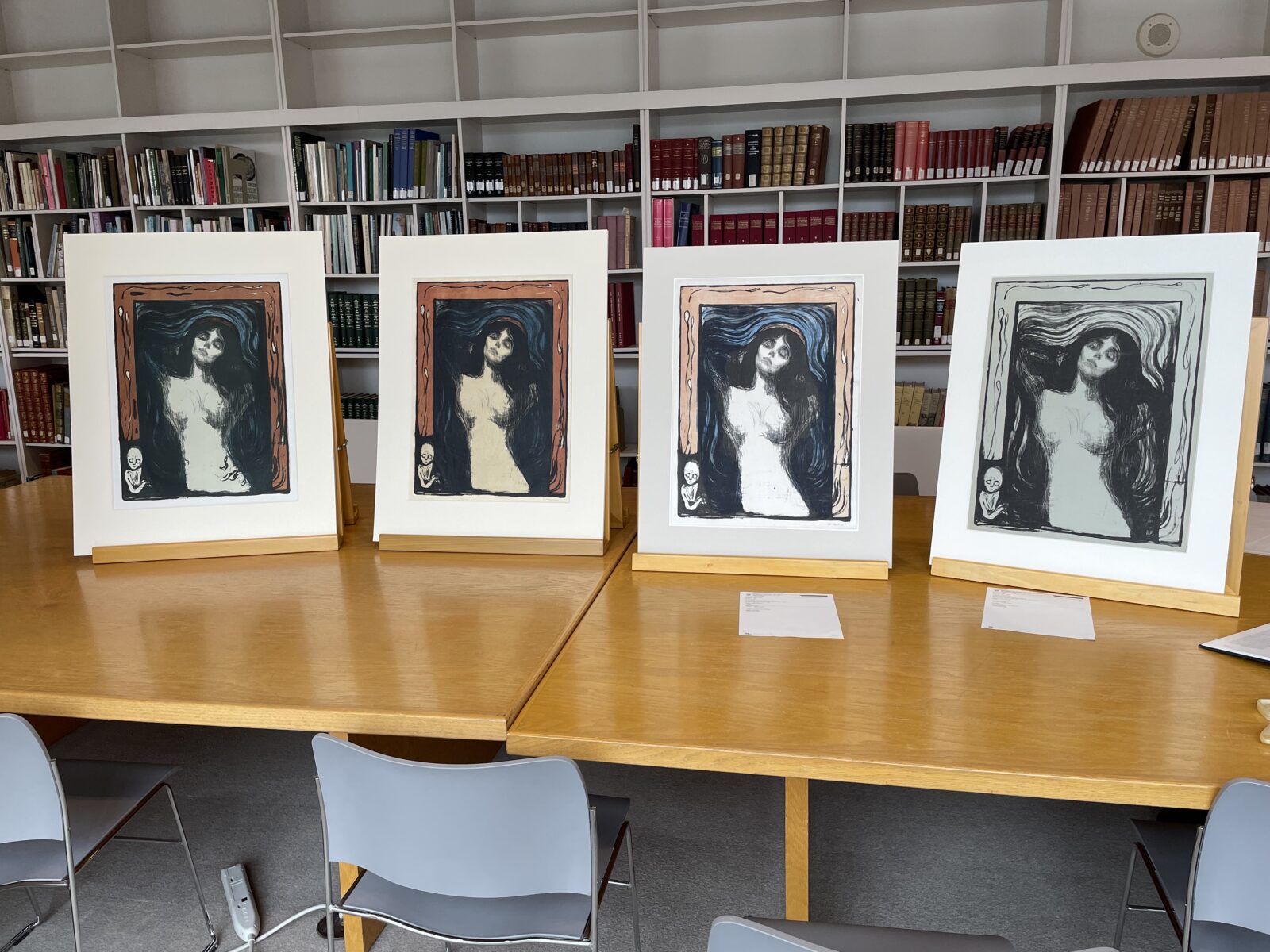

The contemporary moment is relevant. On 1 May 2022, I arrived in Washington, DC to conduct research as a Senior Visiting Fellow at the Center for Advanced Study in the Visual Arts. The following day, a draft of the U.S. Supreme Court’s decision overturning Roe v. Wade was leaked. Between early May and the release of the final decision on June 24, I intensively studied Munch works in the museum’s print room, paying particular attention to four impressions of Madonna (Figure 3) while regularly walking 20 minutes to the Supreme Court to protest the decision. And since then, I have been grappling with how to responsibly pursue this work given the anti-abortion movement’s ongoing weaponization of the birth control movement’s involvement with eugenics, including in footnote 41 of Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization. As legal scholar Melissa Murray predicted, eugenics, as used to control Black people’s reproduction, would become a key alibi for overturning Roe’s settled precedent.3

: :

In 1897–99, Munch painted another “Madonna” image. Based on a scene that the artist claimed to have witnessed, Inheritance depicts a mother weeping over a syphilitic child (Figure 4): “the sobbing Wife whom I saw at the Hospital for venereal Diseases— . . . —I had to paint this Face twisted with Despair . . . —And the querying— suffering Child’s eyes I had to paint the way they gazed from the sickly yellow Child’s body – . . . ”4 Munch’s formal distortions and his use of color to depict sickness led some critics to read death, even murder into the scene. A critic writing in 1906 hesitated between identifying the entity on the mother’s lap as an expulsed fetus or an infant, describing it as “greenish fruit, discoloured to l’eau-de-vie, which is going to return to the alcohol of the fetus jars . . . head too big . . . and, a horrible detail, the immense brown gaping eyes that look around.” This critic picked up on the “querying” eyes to pose his own questions about the work’s ambiguities: “Abortion or infanticide, despair or madness?”5 In 1905, another critic raised the same issue about Munch’s Madonna, asking whether the artist, in creating the work, “had wanted us to meditate on the tragic destiny that pushes so many women in our sad society towards voluntary abortion or, worse still, infanticide.”6

“Tragic destiny” struck in Kristiania, the city now called Oslo, in 1901, when six women, including a midwife, were arrested and charged with crimes ranging from fraud to neglect, mistreatment to murder relating to nineteen children. In 1902, in a painting he called Foster Mothers in Court, Munch depicted the sensational trial of the “foster mothers,” which resulted in two lifetime sentences for murder and three minor sentences for women deemed to have been accomplices (Figure 5).7 The “foster mothers” were accused of having preyed on unwed mothers. They had, according to the prosecution, taken in large numbers of children for money, neglected and mistreated them to the point of death, and covered up their deaths by hiding the bodies and producing dubious medical certificates.

Munch also exhibited the painting as Angelmakers, a term used at the time to refer to both abortion providers and murderers. A contemporaneous illustration by Charles Léandre shows a monstrous abortion provider in a room with fetuses in jars, including one with a tiny wing and images of winged putti, telling a pregnant potential client that “here we make angels” (Figure 6).8

Although Munch’s portrayal of the “foster mothers” courts the grotesque, it is much more ambiguous than Léandre’s “monster of monsters,” suggesting the complex and tragic circumstances that led to their crimes and giving, relatively speaking, at least equally or more human faces to the three seated accomplices than to any member of the public or institutional authority in the courtroom.

At the time of the trial, abortion had long been illegal in Norway, but with ambiguity written into the statutes. Paragraph 245 of the new penal code of 1902 attempted to remove that ambiguity, clarifying the matter—to the detriment of women: “A woman who, by means of expulsion or in any other way, unlawfully kills the fetus with which she is pregnant, or contributes to this, is punished for expulsion of the fetus with imprisonment for up to 3 years.”9 The 1901 trial of the foster mothers thus became a watershed moment in Norway, catalyzing debates over women’s reproductive rights just as the criminality of abortion was being reaffirmed.

The case of the foster mothers was a decisive moment for the activist Katti Anker Møller, who wrote her first articles on “Unmarried Mothers” in the feminist journal Nylænde in 1901, as the arrests were made and the trial got under way. In these early writings, Møller expressed sympathy for “abandoned” unmarried mothers who, “with dark prospects for the future,” might go so far as to commit infanticide. To avoid this, and “with the saga of the foster mothers fresh in mind,” Møller called for new financial provisions for unmarried mothers and the establishment of modern maternity homes.10 Thereafter, she established herself as an early voice for reproductive justice and at the forefront of the struggle for women’s suffrage.11

While Anglo-American birth control movements led by Margaret Sanger in the U.S. and Marie Stopes in Britain focused on contraception and avoided including abortion in their agendas, Møller drew support for her increasingly vocal stance on abortion from colleagues in Russia, Germany, and Sweden.12 In a speech given in 1915, two years after Norwegian women obtained the right to vote, Møller advocated for the full decriminalization of abortion. She argued publicly that the right to abortion was distinctly modern, closely tied to women’s full citizenship and emancipated consciousness: “ . . . a Fetus is part of the woman herself, [and] she must have control and the right to determine it, in the same way that freedom and control over one’s own body is a natural right for every citizen in a free state.” Møller went on to say: “Punishment for fetal displacement can no longer be reconciled with the freedom of personality which is the fruit of modern women’s emancipation.” Ramping up her rhetoric, she insisted that a man already had the right “to kill a fetus in the mother’s womb with an infectious disease . . . ; he can give his wife and children syphilis and bring them all to death.”13 This dramatic line of argument equated a woman’s right to “kill” a fetus with what Møller framed as man’s legally sanctioned right to murder.

In that same speech and in keeping with the birth control movement’s focus on promoting “healthier” and “stronger” populations, Møller imagined an “information center” to deliver materials and education on, among many other topics, eugenics. The year after her speech, in 1916, she organized a traveling exhibition to raise money for maternity homes, which included population charts and comparative displays such as a “working-class apartment” contrasted to a hygienic “modern apartment.” These focused visitors’ attentions on how to improve living conditions and reduce the birth rate among the working class. That same year, Munch painted a portrait of Møller’s husband, a politician who publicly supported his wife’s activism, confirming, at the very least, that the artist was aware of her initiatives.

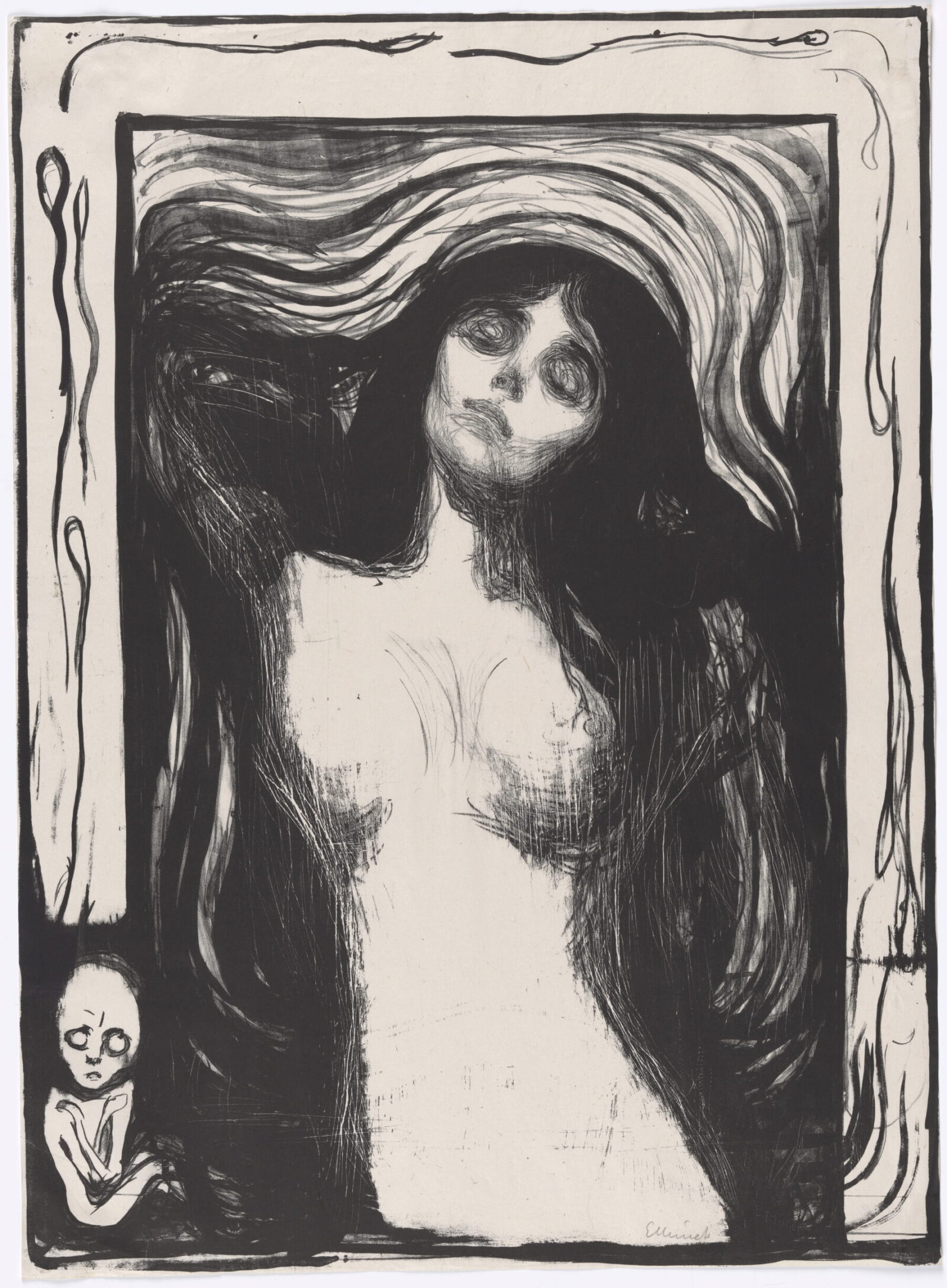

Munch made the first lithograph version of Madonna in 1895, printing it in only one colour, most often black. The border of the work acts, in the words of Nora Heidorn, as a “visual membrane” separating the woman from the fetus (?) and sperm (Figure 7).14 Crouched in the lower lefthand corner, the little figure looks up towards the woman with large, worried eyes, echoing her own heavy-lidded eyes, which are either closed or possibly looking down towards it. Either not yet in utero and thus foreshadowing pregnancy or “expulsed” from it, to echo the 1902 law, the fetal figure is ambiguous, very much “querying.” In 1902, the same year that he painted Foster Mothers, Munch prepared new lithographic stones for Madonna to create three- and four-color impressions, which significantly altered the effect of the work (Figures 8 and 1). The graphically intense flat areas of color, and particularly the red border, amplified the image’s potential as propaganda. Acknowledging the complexity and ambiguity of the issue, the print asked—I might even say it implored or forced—the viewer to keep questions, including religious questions, about a woman’s embodied relationship to a fetus or child (and thus reproduction and reproductive rights) front of mind.

The color lithographs also raise questions about the figures’ whiteness and therefore about race and eugenics. In the three-colour impressions, printed in black, red, and blue, the white skin of the woman, the fetus (?), and the sperm are devoid of ink, constituted by the white, grey, or beige color of the paper on which the work is printed (Figure 8). However, in the more luxe four-color impressions, often printed on thin Japan paper, a khaki stone, inked barely a shade darker than the thin cream paper on which the image is often printed, adds tonal color to the figures’ skin (Figures 1 and 2). These impressions thus draw attention to the whiteness of flesh, which becomes printed ink rather than blank paper. But that flesh, of Madonna and the fetal figure, is a slightly off, sickly tone, like the “greenish fruit” of Inheritance. This off-whiteness thereby connotes anxieties over degeneration and the so-called “race suicide” that eugenicists hoped to address through population control measures such as contraception, sterilization, and abortion.

: :

Four distinct impressions of Madonna are the centerpiece of a collection of over 300 works on paper by Munch that began entering the NGA through the philanthropic activities of a family whose wealth is in part inherited from Clarence J. Gamble, a grandson of the co-founder of Proctor & Gamble. A medical doctor, Clarence Gamble put his training and his money in the service of the birth control movement led by Sanger often under the banner of “population control.” In 1957, Gamble founded Pathfinder International which, since 2020, has been reckoning with how its founder’s racist and eugenicist beliefs long informed the organization’s work. Gamble’s daughter and her then husband, long themselves active in Planned Parenthood and Pathfinder, inaugurated the Munch gift to the NGA in 1990 with two prints including a four-colour impression, with border, of Madonna.

Prefacing an exhibition catalogue of the collection in the 1980s, the donor highlighted the “extraordinary contrasts” afforded by her twin passions for Munch and the “population field,” which led her to go from an audience with Norwegian royalty in the midst of a snowstorm to catching a plane to Kenya where, “under tropical skies I was being welcomed in a village by the women club members of the Maen-deleo ya Wanawake movement, their bright skirts and turbans, singing and dancing as they came along the road to greet us. The only words I could clearly understand were ‘family planning, family planning.’ I knew my mission was understood!” Without starting a new paragraph, she continued, “I’m happy to say Princess Sonia was able to come as an honorary patron to the opening of the Munch show at the National Gallery of Art in Washington [in 1978], and I was privileged to have her later for lunch to meet some of my women friends.”15

The donor’s reminiscences of her travels assert a stark contrast between snowy Norway and the “tropical skies” of Kenya, while emphasizing her ability to move easily back and forth between those two worlds. At the same time, her “mission” in Kenya is characterized as so righteous as to be immediately “understood” despite her only being able to understand one phrase. Emphasizing Munch as “an artist for all people of any age, sex, era, or country!”, as she inscribed to me in a later catalogue, the donor repeatedly mobilized her passionate care for Munch and his art as a sign of her own passionate care for humanity writ large, her willingness to face the potential tragedies of sex and reproduction visualized in Madonna, and to do so on behalf of all humankind.

Katherine M. Bell argues that white savior discourse, especially as deployed through celebrity philanthropy, characteristically involves a tension between representations of the Other and “a rhetoric of human communality.” Using Madonna (the contemporary performer) and Angelina Jolie as exemplary cases, Bell explores how these white celebrities project “near-divine greatness” through their representations of motherhood, including adoptive motherhood to Black and Asian children. Drawing on Gayatri Spivak, this representation, Bell argues, effectively “ventriloquizes the subaltern, produc[ing] a universal subject that matters only in relation to its capacity to serve the ventriloquist.”16 In her preface, the donor literally ventriloquizes the Kenyan women—“family planning, family planning”—imagining them, despite her admission of only partial understanding, as fully in support of her mission and asserting her own ability to speak for them. Similarly, with a lifelong dedication to the “Great Cause,” with financial means and white privilege, the donor sets aside the topicality of Munch’s Madonna to claim, for better and for worse, a strong connection between her universalist approach to both Munch and reproductive rights.

The tension between representations of an Other and ventriloquizing claims to universalism is likewise embedded in Munch’s work. In Madonna, Munch leverages his white masculinity, his privilege to create an artwork, to reproduce and disseminate a print widely, as well as his privilege to speak for, to shock, and to scandalize. But to what ends? To keep the struggle for reproductive rights, including abortion, alive and urgent? To stay with the (political) ambiguities and complexities of fetus or baby, miscarriage, abortion, or infanticide? To assert a kind of allyship? To call for the improvement of the human race in the face of degeneration?

And why did Munch send a version of Madonna without its bordering frame to the Armory show in 1913, excising from the image the sperm and the fetus, and thus the contemporary context of the struggle for reproductive rights? It seems highly unlikely that at this early moment in that struggle he was conscious of the differing stances on abortion that would come to characterize Scandinavian and Anglo-American birth control movements. More likely Munch chose to avoid provoking a new U.S.-based audience who were much less familiar with his two-decades-long history of courting controversy and scandalizing the public in Europe. But look more closely, and you will see that the fetus is not entirely absent. Parts of the fetus linger at the edge of the image reminding viewers that women’s rights can never be wholly separated from reproductive justice and that, at the same time, “universals” such as “Woman,” “rights,” and the “Great Cause” can do much to harm the lives of particular people and communities.

: :

Endnotes

- Gerd Woll, Edvard Munch: Complete Graphic Works, 2nd edition (Philip Wilson, 2012), 67.

- The Madonna motif is widely discussed. As a starting point see, Ingebjørg Ydstie, ed. Madonna, trans. Francesca M. Nichols (Oslo: Munch Museum 2008). This essay is deeply indebted to the ongoing conversations I have had with Nora Heidorn about Madonna, contraception, and eugenics.

- Melissa Murray, “Race-ing Roe: Reproductive Justice, Racial Justice, and the Battle for Roe v. Wade,” Harvard Law Review 134, no. 6 (April 2021): 2025–2102.

- Edvard Munch, MM T 2800, Munch Museum, dated 1988. Sketchbook (accessed 25 February 2025).

- William Ritter, “Un peintre norvégien: M. Edvard Munch,” in Études d’art étranger (Société du Mercure de France, 1906), 97.

- Vittoria Pica, “Trois artistes d’exception: Aubrey Beardsley, James Ensor, Edouard Munch,” Mercure de France (August 1905), 528.

- Gerd Woll, “Harmløs karikatur eller bitende sosialkritikk? Pleiemødre i lagmannsretten,” Kunstavisen (2 March 2020): https://kunstavisen.no/pleiemodre-i-lagmannsretten (accessed 25 February 2020). See also Hege Duckert, “The Angel Makers,” in Lifeblood—Edvard Munch, edited by Allison Morehead and Heidi Bale Amundsen (MUNCH, 2025), 223–227.

- See Elizabeth K. Menon, “The Fetus in Late 19th-Century Graphic Art,” Nineteenth-Century Art Worldwide 3, no. 1 (Spring 2004): https://www.19thc-artworldwide.org/spring04/anatomy-of-a-motif-the-fetus-in-late-19th-century-graphic-art (accessed 25 February 2025).

- Straffeloven 1902, §245: https://lovdata.no/dokument/NLO/lov/1902-05-22-10 (accessed 28 February 2025). See also Kari Tove Elvbakken, Abortspørsmålets politiske historie 1900–1920 (Universitetsforlaget, 2021), 26–50.

- Katti Anker Møller, “Ugifte Mødre,” Nylænde (15 April 1901), 116–117; “Forlslaget til Lov om underholdningsbidrag til børn, hvis Forældre ikke har indgaaet ægteskab med hinanden,” Nylænde (15 November 1901), 345–346.

- On Møller, see Hege Duckert, Katti Anker Møller: Å bestemme over livet (J.M. Stenersens Forlag, 2023).

- Elvbakken, Abortspørsmålets politiske historie, 28–39.

- Katti Anker Møller, Moderskapets Frigjørelse (Det Norske Arbeiderpartis forlag, [1915] 1923). See also Ida Blom, “‘How to Have Healthy Children’. Responses to the Falling Birth Rate in Norway, c. 1900–1940,” Dynamis 28 (2008): 151–174.

- Nora Heidorn, “Reading Munch’s Madonna through the lens of contraception,” in Lifeblood—Edvard Munch, edited by Allison Morehead and Heidi Bale Amundsen (MUNCH, 2025), 231.

- Sarah G. Epstein, “A Collector’s Preface,” in The Prints of Edvard Munch: Mirror of His Life, edited by Jane Van Nimmen (Allen Memorial Art Museum, 1983), 7.

- Katherine M. Bell, “Raising Africa?: Celebrity and the Rhetoric of the White Saviour” PORTAL 10, no.1 (2013): 2, 3, 7.