In Ancient Rome, male doctors were summoned during childbirth only if labor proved difficult. Instead, it was midwives who played the literal and figurative role of a physical and emotional support in childbirth—a support captured in the word obstetrix, which comes from the Latin verb obstare, “she who stands in front/opposite.” This defining feature is reflected in representations of midwives, which often depict a midwife positioned before a mother in a posture of support, as in Figure 1. In this poignant scene, a mother grips the back of her kline with her right hand and the midwife’s back with her left. The gesture conveys reliance and trust through a tangible connection between women: the fate of the mother and her child is in the midwife’s hands.

Then, as now, the male elite were suspicious of these women with so much medical expertise over childbirth. Even Soranus of Ephesus, who attempts to define and defend the training of midwives, observes an underlying aura of superstition and secrecy: his ideal midwife is well trained and free of superstition, but she keeps secrets and should not be greedy, lest she be tempted to perform an abortion for money. Although abortion was not illegal, a Roman midwife’s role in providing abortions seems to have colored literary portrayals, emphasizing superstition and witchery as a means of deterring women.

With such a biased archive, where should we look for better accounts of ancient midwifery? Perhaps surprisingly, not to accounts of birth but to what comes after death: epitaphs, whose subjects were often idealized and viewed in communal spaces, provide a key contrast to literary sources. Moreover, their nature not just as text but as image transmit meanings from beyond the literate elite. Composed by close family or friends, epitaphs reflect how midwives were seen by broader audiences: men, women, and children of varying classes and literacies.

Most modern viewers engage with epitaphs in museums as objects out of context, dappled within a collection of objects from different times and spaces. In this context, it is difficult to imagine the experience of viewing an epitaph or how its message fits within a collective. For the privileged few who visit a columbarium or tomb on the Isola Sacra at Ostia, the sensory transition is striking and otherworldly; visitors enter through a narrow doorway, down steep steps, and into a dark, damp, and dimly lit space that spreads out protectively, obscuring the soundscape of the outer world. The experience mimics one’s arrival and departure from the mortal realm, and is particularly relevant for a midwife, whose occupation faced both outcomes. Inside, intricately painted walls and ceilings present a dizzying array of spaces that leave a lingering sense of vertigo. Relationships represented within these structures were diverse and dynamic, echoes of an intimate community whose voices have since been lost, save for brief but poignant memorials of friends and family. Face-to-face engagement with these inscriptions illustrates the importance of a midwife’s role, defining her place and identity for her loved ones and her community.

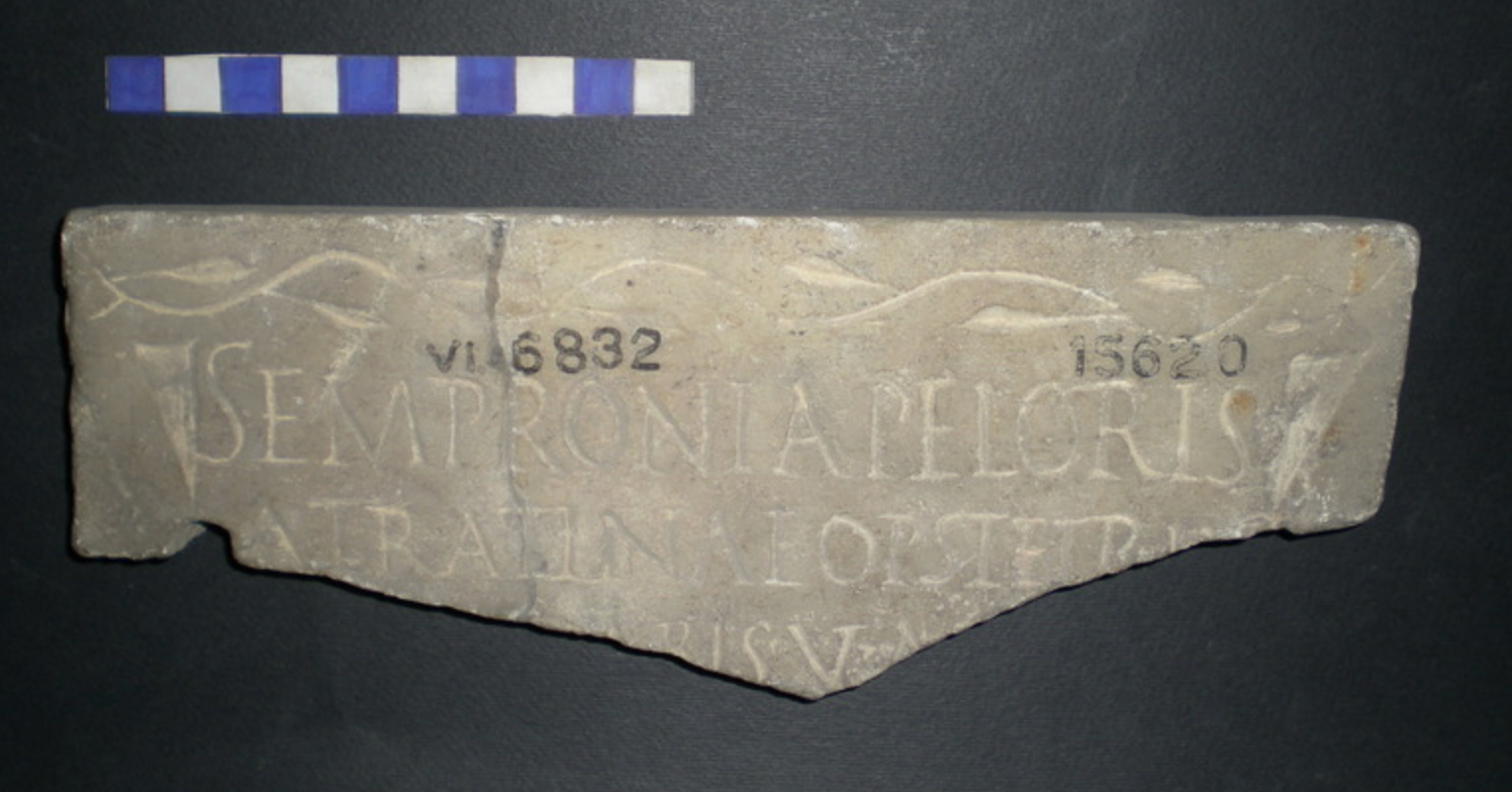

Consider the small columbarium set up by the elite Semproni Atratini and Atratinae family for their slaves and freedmen (ca. 30 BCE-30 CE) off the Via Latina.1 It contained 20 inscriptions, 15 incised in plaster at the top of an elaborate design with spaces for four marble tabella ansata below four large niches. All four marble tabellas are beautifully framed with floral or leafy elements or triangular designs. The epitaph of the midwife Sempronia Peloris, whose first name matches the family and whose second name is Greek for “mussel/clam,” stands out as both the only name of a woman and the only person for whom an occupation is recorded in the marble (Figure 2). The tablet carried lovely lettering in a prominent space below a niche. The flowing leaves, painted red in other epitaphs, add a tone of grace: curving floral lines frame and contrast with the precise geometry of the carved letter.

Sempronia Peloris, Atratinae opstetrix̣ [—]ṛis, v(ixit) a(nnis)[—]

To Sempronia Peloris, midwife to the Atratina . . . ris? She lived . . . years

Sempronia Peloris occupied a place of esteem in her community, but her status is not explicitly stated. The four other tabella include ornate decoration, marking affiliations with family as well as unique personal details: the freedman Lucius Sempronius Laethus lived 113 years(!) and Lucius Sempronius Faustus, mourned by his mother after only 11 years, boasts a similar leafy framework. Peloris’s name and inclusion with other liberti suggest that she was of free status, but if she was enslaved, her inclusion would be all the more exceptional.

The emphasis on Sempronia Peloris’s name and career contrasts with the smaller painted plaster niches inscribed in stucco. Of the fifteen plaster texts, seven are women and all have two names, but only one has a praenomen (first name): none refer directly to free status. These texts record one other occupation: Lucius Sempronius Smyphorus, a doctor (medicus). Like Peloris, Symphorus’s names and Greek cognomen suggest freedman status, though not explicitly. Unlike Peloris, his occupation is not directly connected to the household and his text, scratched into plaster at the top of the wall, was visually less prominent and accessible. We may be surprised that a midwife, possibly enslaved, was afforded such a monument, while a doctor, potentially a libertus, was marginalized.

: :

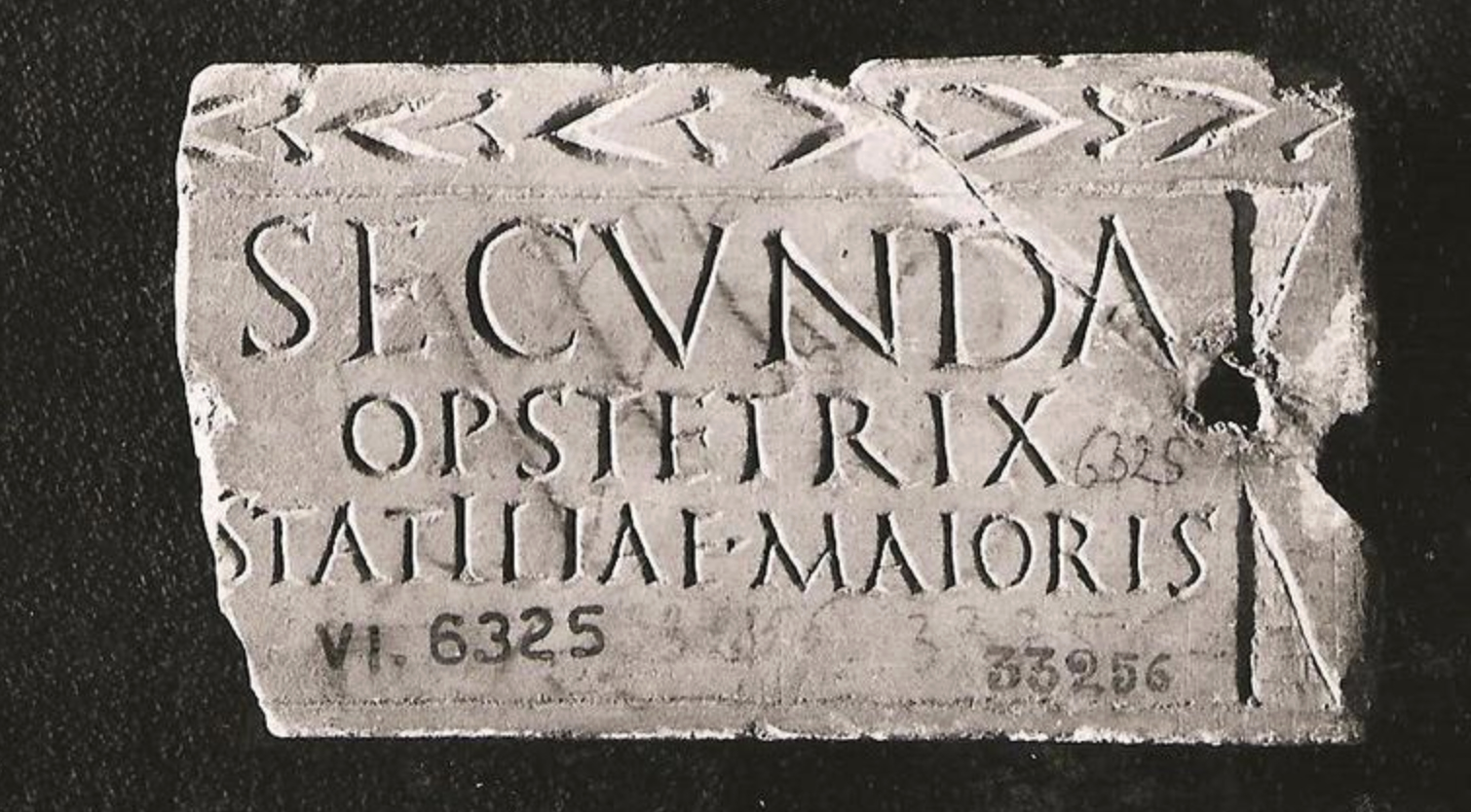

The columbarium set up by the well-known Statilii family (ca. 1-50 CE) off the Via Labicana near Porta Maggiore provides similar evidence re-ordering our sense of the hierarhcy between doctor and midwife in Roman society. This structure held 700 loculi and 382 inscriptions, which were miraculously intact when it was discovered in 1875. Epitaphs attest to dozens of male occupations and eight female roles. Despite her status as a slave, the midwife Secunda’s epitaph bears a striking similarity to that of Sempronis Peloris: a marble tabella ansata with a floral framework and text that defines her occupation and close connection with a specific family member: “Secunda, midwife to Statilia the Elder.” While a single name suggests she was a slave, the ornate inscription reflects a respected role and a unique bond between the two women (Figure 3).

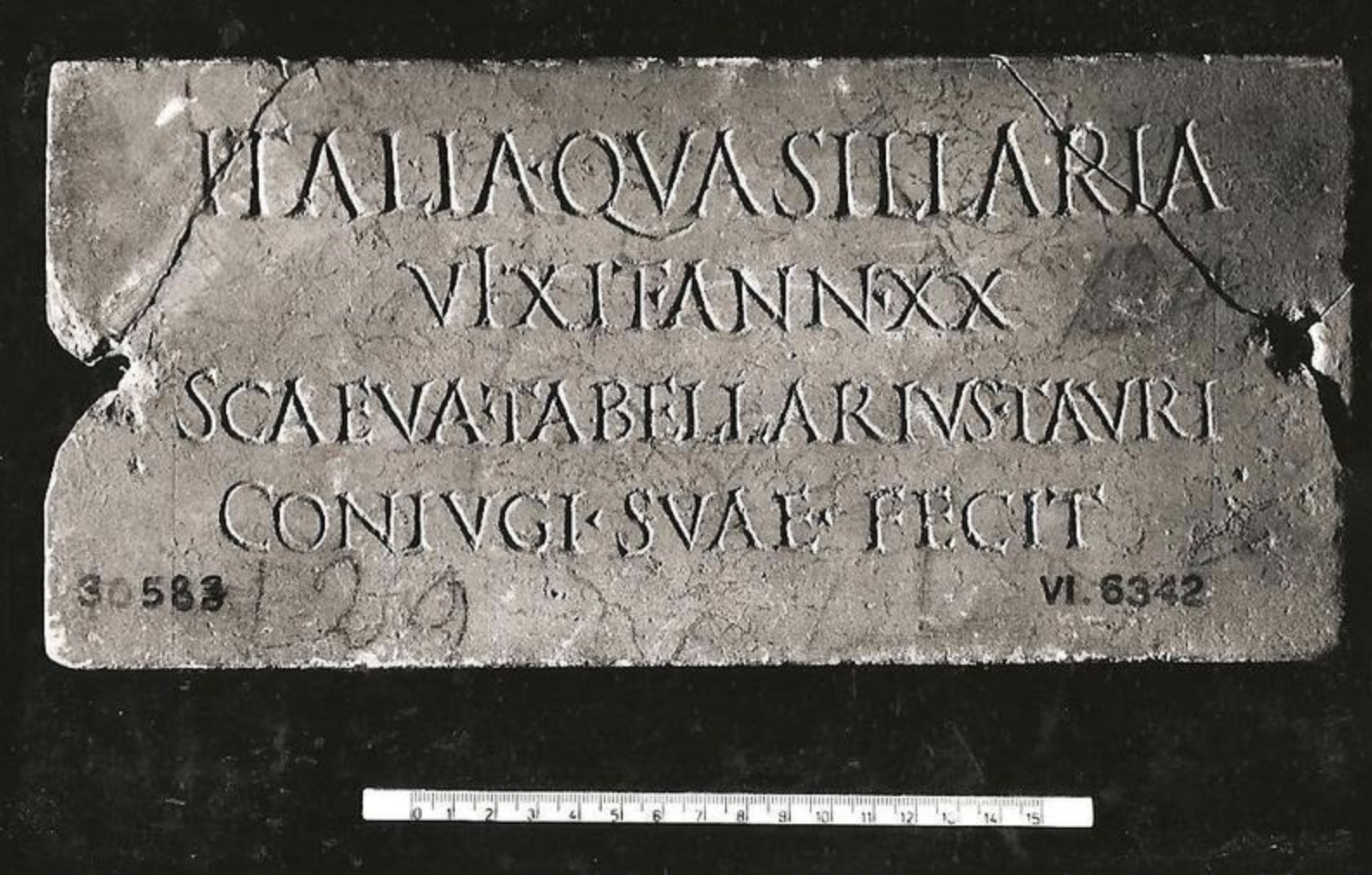

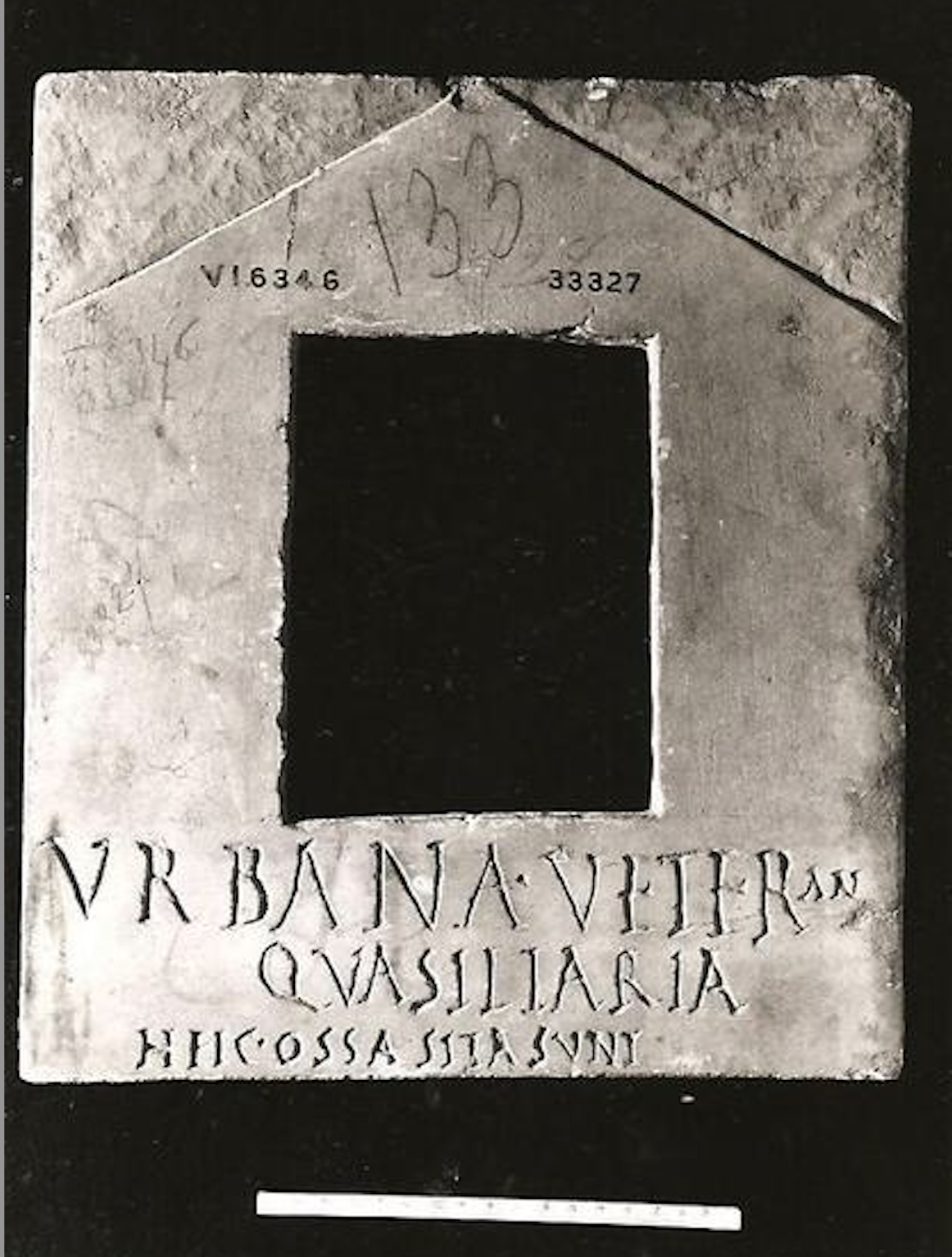

Its original location is not known, but holesindicate that it was nailed outside a niche, where it would have been eye-catching and served as a poignant memorial for her family and friends. How did Secunda compare with other working women in her community? Echonis, an enslaved wet nurse (nutrix) of Statilia the Younger’s children, was honored with a marble urn for a large niche (Figure 4). Her name, role, and association with the family, as well as the urn’s shape, were recognizable to friends and family. Meanwhile, Italia, an enslaved woman married to a courier for the Statilii Tauri, has a lovely marble tabella carved in graceful letters. A bond with her spouse and his connection to the Statilli are preserved in a large, well-executed inscription (Figure 5). In contrast, Urbana Veterana, who like Italia was a “basket wench,” has a humble inscription even though she has two Latin names: scraped in child-like forms which are more difficult to read.

The theme that emerges from these epitaphs is that class and occupation do not necessarily dictate the quality or prominence of a monument. Close connections to friends and family seem to play an equally important role in how individuals are represented. Although Sempronia Peloris and Secunda may have had different social statuses, their roles and connection with female patrons were conveyed in the text, illustration, and arrangement of their inscriptions, which occupied a unique space in the funerary community.

Although it is men and predominantly male doctors who monopolize the textual archive of ancient Rome, these epitaphs teach us to go looking for the subaltern expertise of women and midwives. The voices and relationships of working women have not been lost to the ages, but perhaps they have merely been unseen, due to a lack of accessible sites and materials. Recovering the entangled lives of ancient midwives and their patients also writes a history of ancient abortion as one component of a much larger matrix of reproductive care. While the right of women to author their own reproductive destiny is under threat today—arguably more so than in ancient Rome, where abortion was not illegal—the epitaphs of Sempronia Peloris and Secunda also provide us hope for the persistence of feminist knowledge underneath the dictates of official patriarchal law. Although abortion is not a narrative featured directly in Roman Art or epitaphs, the close relationships and the bond of trust between pregnant women and a midwife remain a prominent aspect of both sources. It is a timeless bond that any pregnant woman can understand: the immense weight of care and concern that falls upon one’s shoulders, and the inestimable value of someone who will stand at your side to share it.

: :