What can paint and marble tell us that trips to the archives might not? As a historian, I was prompted to ask questions such as this while reading these essays exploring representations of abortion in art and literature. The works considered here range from novels to a variety of visual art forms, from oil paintings to marble statuary to mixed media. Taken together, they suggest that artistic representation can reveal what is often hidden. In the case of abortion—often illegal, often shameful, at times known more through whisper networks than official archives—so much is concealed.

Works of art and literature help us to see that abortion has been woven into women’s experiences always and everywhere, because there have always been women who did not want to be pregnant. Anecdotally, middle-aged women in the US and the UK have told me that their mothers told them, in a matter-of-fact way, that they routinely aborted as the only means of birth control available to them in the 1950s and 60s. Paula Rego’s paintings, analyzed by Márcia Oliveira in this cluster, gives those matters of fact a material reality. In Portugal, family planning only became available after 1976, so abortion was the primary means of birth control. Rego’s work was, in Oliveira’s words, “a form of contesting the secluded, hidden, and often too secretive affair of having an abortion.” Her 1998 pastel series on abortion underlines the political: working-class women relied upon unreliable and dangerous providers, whereas Rego could afford better, albeit still illegal care.

Historians always struggle to research things that are illegal; they were carefully concealed at the time they happened, so doubly difficult to access today. Where Rego’s pastels focus on women recovering in domestic settings, underlining the ordinariness of abortion, Ed Keinholz’s paintings point to the violence and degradation seemingly inherent in illegal procedures. As Johanna Gosse discusses, Keinholz’s graphic The Illegal Operation (1962) depicts the aftermath of a so-called “back-alley” abortion.1 While abortion was illegal in all 50 states, estimates are that a million illegal abortions were performed every year in the early 1960s. Some providers were caring and competent, but many were not. A woman might be instructed to meet her contact in a hotel lobby or coffee shop, be bundled into a car, blindfolded, and driven around to conceal the location of the apartment or office to which she has being taken. Providers were described as sometimes being drunk, demanding sex, or suddenly inflating the costs of the procedure.2 While we have a handful of oral histories that narrate such experiences, historians usually rely upon court documents and newspaper accounts of trials to understand illegal abortion in this period. What go missing are the violence and terror often implicit in the experience, so graphically conveyed in Kienholtz’s work.3

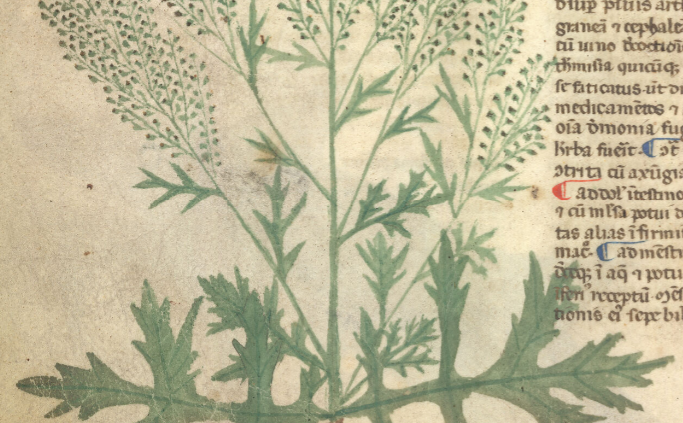

When abortion was illegal, and there was no internet to draw upon, women often relied upon other women for crucial information about which plants might end a pregnancy. Jennifer Nader analyzes novelist Sarah Orne Jewett’s novel The Country of the Pointed Firs (1896), in which a city woman spends a summer in rural Maine learning from a local woman with deep expertise in herbal medicine. By this time, the effects of the 1873 Comstock Act, banning the mailing of any contraceptive or abortion information, had bitten deep. But remarkably, as Nader demonstrates, Jewett encodes a whole array of abortifacient remedies in her story. Jewett was the daughter of a Maine physician who specialized in birthing and baby care, and Jewett accompanied him on his rounds. In the novel, however, the healer Almira is female and provides the narrator with information on a wealth of herbal remedies. Sometimes, abortion is hiding in plain sight.

Herbal knowledge of abortifacients has another layer of meaning for Black women, as Leila Easa and Jennifer Stager indicate in their discussion of Toni Morison’s The Bluest Eye (1970). They discuss the novel’s well-known opening line, “Quiet as it’s kept, there were no marigolds in the fall of 1941.” That phrase, “quiet as it’s kept,” functions paradoxically, telling and not telling all at once. In the novel, the marigold seed dropped into the ground is compared to the rape of Pecola Breedlove by her father. Neither the marigolds nor the pregnancy are productive. Easa and Stager connect this metaphor to the long history of enslaved women drawing upon herbal knowledge, often going back to African practices, conserved over generations of enslavement. Indeed, the plant that made many American enslaver rich—the cotton plant—was used clandestinely by enslaved women to avoid pregnancy. Oral histories of elderly Black people, recorded by Works Progress Administration interviewers in the 1930s, revealed such usage. Women chewed cotton root to prevent or interrupt pregnancy, but were careful to do so secretly, or risk punishment by the enslaver.4 “Quiet as it’s kept” points to the secret-keeping necessary to preserve and sustain this herbal knowledge—and to employ it, alluding to the complex histories of enslaved women’s management of their fertility.

These few examples illustrate how works of art and literature can illuminate crucial aspects of abortion’s many histories that might elude the historian. As important, these works evoke strong feelings in viewers and readers—as they are intended to do. Those emotions can serve as calls to action, galvanizing resistance, in ways that history may not always be able to achieve.

: :

Endnotes

- On the rhetoric of “back-alley abortion” see Emily Winderman, Back-Alley Abortion: A Rhetorical History ( Johns Hopkins Press, 2025).

- See Mary Fissell, Pushback: The 2500-Year Fight to Thwart Women by Restricting Abortion (Seal/Basic, 2025), 192-3.

- See, for example, Patricia G. Miller, The Worst of Times (Harper Collins, 1993).

- Fissell, Pushback, 111-112.