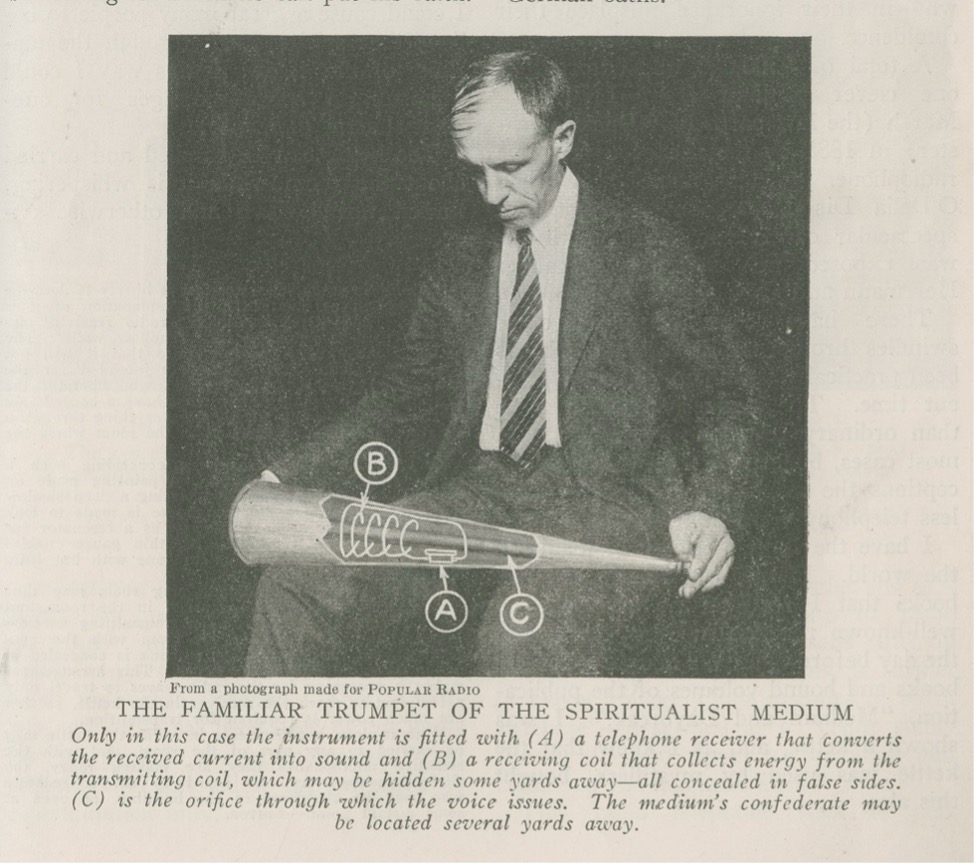

Blurring the lines between the physical and the virtual. Conjuring uncanny visuals. Tricking the senses to induce wonder. Such hallmark features of contemporary extended reality (XR) technologies have fantastical roots with a deeper history. From mediating messages from the afterlife to manifesting the ghosts themselves, the séances of the 19th-century Spiritualist movement extended audiences’ realities through a variety of innovative sensorial techniques that function as predecessors to current technology. We contend that this unique period of history offers fertile ground for conceptualizing and understanding today’s XR landscape,1 a landscape that is still haunted by its enchanted past.

As a research team based at the University of Pennsylvania, we are particularly drawn to Philadelphia’s rich and foundational Spiritualist scene.2 Spiritualism, a new religion in the mid-19th century, was based on the idea of communicating with the dead.3 It rose to prominence in post-Civil War America, where approximately 1 in 50 people were killed in the years of deadly tumult.4 While the earliest forms of purported spirit communication included knocking sounds or the movement of a device that allowed ghosts to spell out messages, mediums rapidly expanded their repertoire to keep an increasingly inured audience engaged.

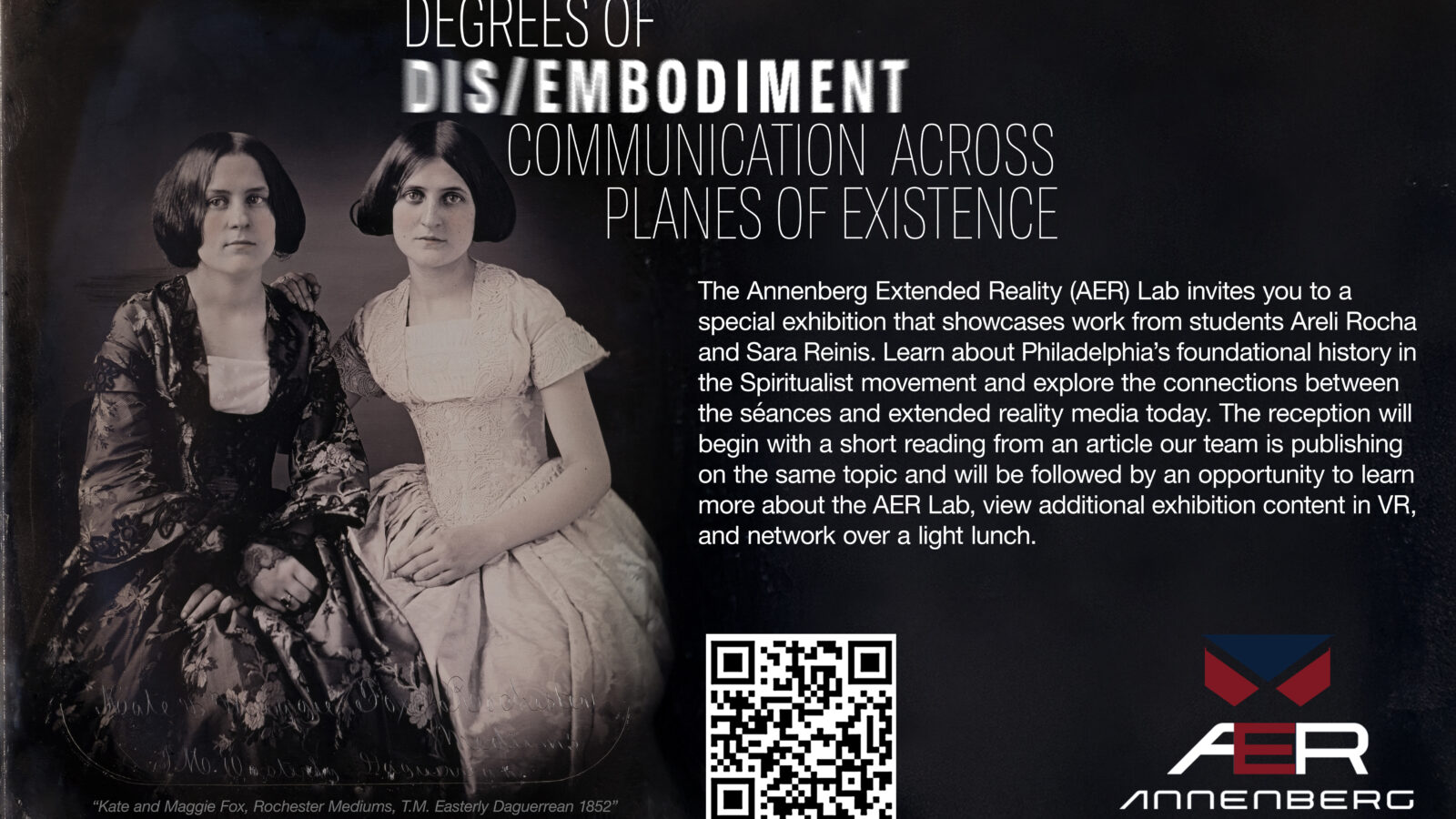

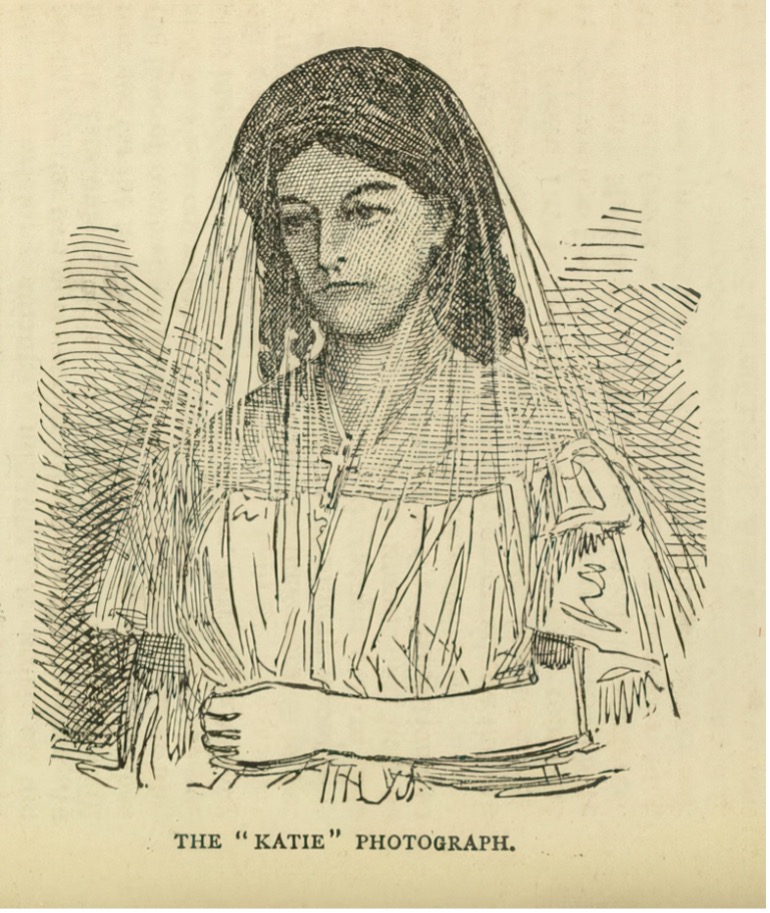

The world took note in early 1874 when a Philadelphia medium named Jenny Holmes announced she was not only in communication with a ghost who called herself Katie King but was able to fully materialize her. For the next eight months, people were mesmerized by the Philadelphia appearances. Séance goers included Henry Wilson, Vice President of the United States, and other prominent politicians who came to see the ghost, shower her with gifts, and hope to leave with a lock of her hair.5

Fig. 2. Drawing of Katie King from a (now lost) photograph. Reproduced in Henry Olcott’s “People from the Other World” (1875).

Then, between December 1874 and January 1875, came a series of catastrophic revelations for the Spiritualist community: Katie King was not a ghost, but a Philadelphian actress named Eliza White, who published a lengthy confession explaining the medium’s methods. Despite this, powerful Spiritualism adherents descended upon the city to investigate the claims and re-prove Katie King’s ectoplasmic truth. Eminent figures, including Sherlock Holmes author Sir Arthur Conan Doyle and Theosophist Henry Steele Olcott tried to revive Katie’s supernatural reality. Spiritualist and philanthropist Henry Seybert donated $60,000 to the University of Pennsylvania (the equivalent of about $2 million in 2025) to endow a chair in part to study communication with the dead—a chair that, in 2025, still exists.

For many, the case of Katie King, and Spiritualism more broadly, was located in the crevices between certainty and uncertainty, materiality and immateriality—and, importantly, possibility and impossibility. Albeit different, the socio-cultural conditions today are ripe again for mediated, seemingly un-worldly experiences of awe and escape. For instance, XR media offers us the possibility to fly in VR (where there is an inter-body tension of un/believability at play), and to see holograms of delebrities (portmanteau for deceased celebrities) perform live.6

Furthermore, for the spiritualists and for the XR creators, technology has been particularly useful in mediating the coexistence of the seemingly incompatible; for instance, the technological strategy that superimposes figures viewed through a pane of glass held at an angle (see Pepper’s Ghost below) is still often employed to create virtual computer screens and augmented reality glasses.

Nonetheless, the tensions of im/possibility and im/materiality as experienced through XR media today are technologically induced and thus, remove the need for other, gendered bodies to appear. Indeed, many XR experiences occur at the individual level, where only technology is necessary for mediation to occur. In addition, whereas many of the early mediums were women, opening opportunities for female visibility and entrepreneurship (which ultimately backfired), research today shows that women are largely sidelined from creating mainstream XR media—though that was not always the case.7

Still, the technologies behind the séance manifestations were not the only forces at play in concretizing the perceived reality of the Spiritualist movement. The political economy, social climate of grief, and legitimacy of various institutions, including the University of Pennsylvania, were powerful bolstering forces. The latter’s involvement in the investigation of modern Spiritualism revealed complex dynamics of observation as ground for claiming truth and fraud, ideas of who gets to be an expert in which realm, and the types of knowledge that count.

Today, educational institutions like the University of Pennsylvania are again at the forefront of championing the seemingly unworldly, including XR and AI research. This work lends further credibility to the rapid adoption of these technologies in society and highlights that illusion and innovation are often interconnected. What is real is ultimately decided by who gets to legitimate.

One of the stories often told about modernity presents a unilinear chronology of disenchantment—a moment in time in which the other-worldly ceased to account for explanations of the world. Reason, ushered in by technology, triumphed. This dichotomy, which often organizes social life today, constantly bursts at the seams.

The unknowability—the mystery-turned-mysticism—surrounding algorithmic technologies and the perceptual realms they create is resonant with periods conceptualized as more enchanted. Black-boxed AI oracles, multimodal experiences caught between two realms, and virtual bodies, all highlight the simultaneous historicity and contemporaneity of coexisting cosmologies materialized discursively and sensorially by technological applications. To ask what is real is to conjure multiple forces at play.

: :

Endnotes

- In this essay, extended reality technologies refers primarily to virtual and augmented reality, as well as artificial intelligence.

- Jean D. Lavoie, The Theosophical Society: The History of a Spiritualist Movement (Universal-Publishers, 2012).

- B. E. Carroll, Spiritualism in Antebellum America (Indiana University Press, 1997).

- J. David Hacker, “A Census-Based Count of the Civil War Dead,” Civil War History 57, no. 4 (2011): 307–48.

- Robert Dale Owen, “Touching Visitants from a Higher Life: A Chapter of Autobiography,” Atlantic Monthly (January 1875).

- Kenny Forbes, “Dead stars live: Exploring holograms, liveness, and authenticity,” Researching Live Music (Focal Press, 2021), 156-169.

- Lisa Messeri, In the Land of the Unreal: Virtual and Other Realities in Los Angeles (Duke University Press, 2024).