Ghosts don’t just appear; they return. In the Chinese language, the character for “ghost” (gui) is a homonym for the verb “to return.” The nature of haunting across languages and cultures is one of recurrence or re-materialisation—even though what materialises is also immaterial (that minima of an appearance we sometimes call an “apparition”). Ghosts waver between substance and ether, visibility and invisibility, presence and absence, anticipation and retrospection. The experience of haunting disrupts progressive linear time and, in the same shiver of breath, disarticulates many of the oppositional binaries—living/dead, for starters—that condition our ordinary frames of experience and knowledge.

In his book Spectres of Marx, to which this cluster’s essays will turn and return, Jacques Derrida explains the “spectre” as that which disrupts an ontology that can conceive only of ordinal presence or absence. Derrida terms this alternative ontology “hauntology.” Within this scheme, the spectre “arrives” in a peculiar way:

Turned toward the future, going toward it, it also comes from it, it proceeds from the future. It must therefore exceed any presence as presence to itself. At least it has to make this presence possible only on the basis of the movement of some disjointing, disjunction, or disproportion: in the inadequation to self.1

Derrida might find a strange inadequation in the very notion of “contemporary hauntings”—that is, in our attempt here to “date” the ghost to the now-time of our current moment. If by “contemporary” we mean that which belongs to the present, haunting can never be contemporary in a pure or unmixed sense; haunting hybridizes the present, extending it analeptically and proleptically in both directions. If, however, we mean by “contemporary” that something shares the same time as something else—naming two things as coeval, for example—then we might say that haunting is the very spirit of the contemporary, of contemporaneousness: the ghost, like Walter Benjamin’s “dialectical image,” crystallizes “in a moment of danger” as a figural “constellation” of past and present. Haunting makes past and present, present and absent, uneasy cohabitants of a nonidentical present.

Nevertheless, there’s no way around it: ghosts are having a moment now.Today we are seeing a renewed focus, in both art and criticism, on the matter of ghosts and haunting. This is distinct from the haunting we expect in genre work—gothic, horror. Instead, in these works we frequently witness the eruption of the ghostly into or alongside a putatively realistic scenario, and very often a scenario driven by the crises of contemporary culture. To give just a few examples, we have Jesmyn Ward’s Sing Unburied Sing, Hari Kunzru’s White Tears, Doireann Ní Ghríofa’s A Ghost in the Throat, Fred D’Aguiar’s Feeding The Ghosts, Andrea Actis’ Grey All Over, Tyehimba Jess’ Olio, M. NourbeSe Philip’s Zong!, and Tessa Hulls’ Feeding Ghosts. Cinematic apparitions include David Lowery’s A Ghost Story, Mati Diop’s Atlantique, Remi Weekes’ His House and Steven Soderbergh’s Presence. Meanwhile, literary criticism and theory have also shown a renewed tendency towards the spectral as both ontology and metaphorics; Avery Gordon’s Ghostly Matters, Christina Sharpe’s In The Wake, Esther Peeran’s The Spectral Metaphor, David L. Eng and Shinhee Han’s Racial Melancholia, Sadeq Rahimi’s The Hauntology of Everyday Life, and several works by Fred Moten and Stefano Harney. These works bear collective witness to a broader critical return—given the so-called “spectral turn” of the late 1990s, occasioned by the publication of Derrida’s Spectres of Marx—to haunting as a subject of animating, or at least un-dead, interest.

This resurgent interest in ghosts raises a host of questions. These are the questions we shunted onto the authors of this cluster, who answer them in diverse and intriguing ways: How does the strange temporal jag figured by the appearance of the ghost place a kind of pressure on the very concept of “the present”? What is the relationship of haunting to other forms of lingering or “present” absence, as inscribed at the heart of traumatic histories of racial or sexual violence? How do different media or art forms haunt each other, and haunt us? How should we come to terms with the experience of haunting, and what can it tell us about the arts of the present (and their contemporary analytics)?

The impetus for this collection of essays came from a couple of different places. David has recently completed a book, Holding the Ghost, that positions the ghost as the key figure of the contemporary—an era in which we’re haunted by multiple crises which threaten to foreshorten our future, rendering us both haunted and ghostly. Holding the Ghost argues that the motivating factor for the current profusion of ghosts across literary fiction, cinema, poetry, art, theory and non-fiction is the desire to participate in a kind of speculative historical materialism, one that incorporates not just “how did we get here?” but also “where are we going?”. The book’s titular term, ‘holding the ghost’, names a dialogic, spatiotemporal relation with the ghost, one that identifies a pathway for survival: the ghost that we hold is, simultaneously, that of another with whom we are in dialogue, and, possibly, our own.

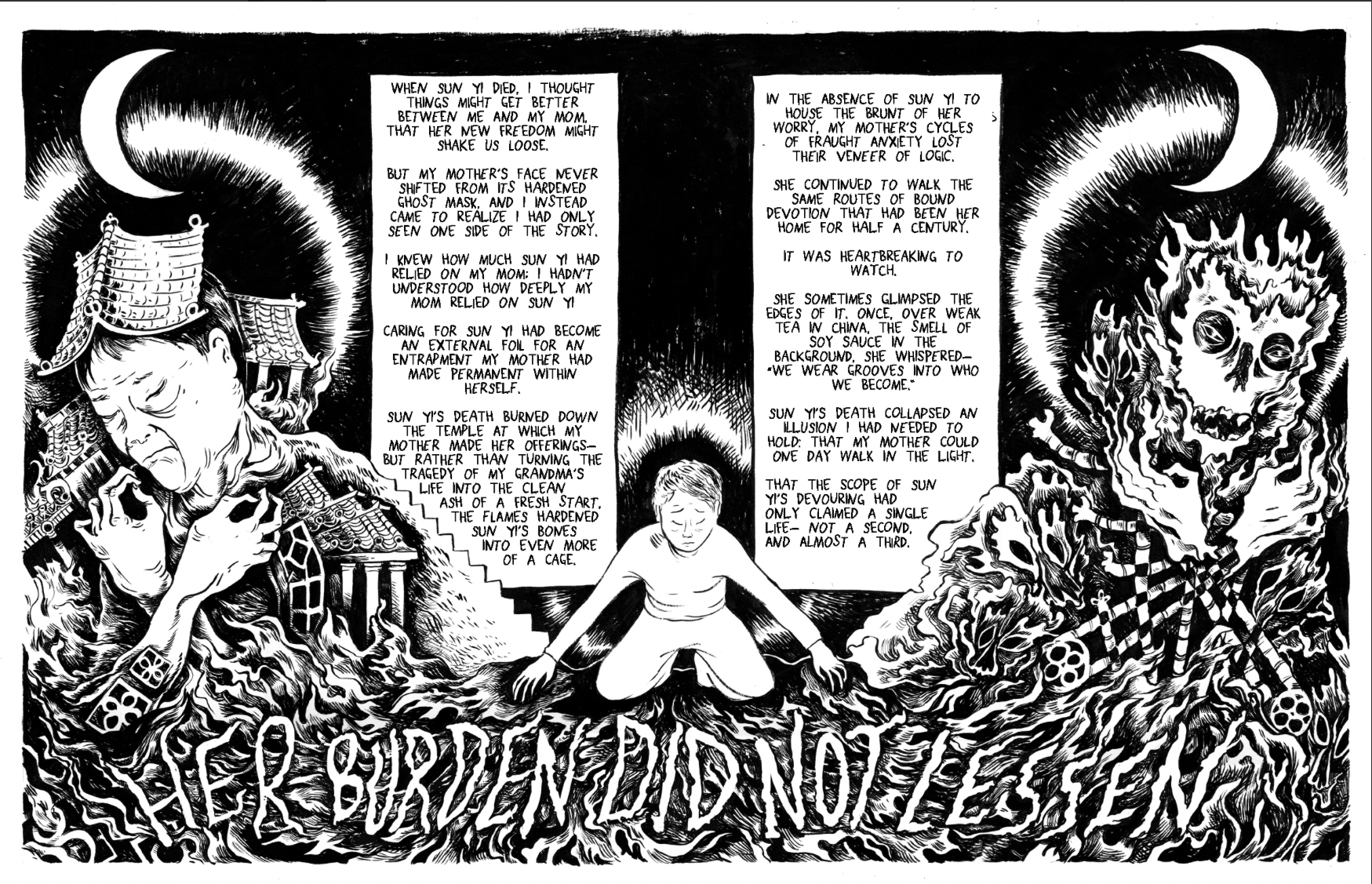

Emmy, for her part, began thinking about “holding ghosts” in relation to writer, artist, and adventurer Tessa Hulls’ Pulitzer Prize-winning graphic memoir debut, Feeding Ghosts (2024).2 Hulls presents the story of her Chinese grandmother, Sun Yi, whom she has grown up knowing only as “a shell to hold her ghosts.”3 At the end of her book, Hulls frames her own project as a different form of ghost-holding: a reconciliation or embrace, even a rehabilitation and homing, that reintegrates the dissociated trauma of the ghost and heals the family. “Isn’t this, in the end, what this story is about? The longing to hold. The longing to be held. And all the ghosts that stand between mothers and daughters who do not know how to access their own yearning.”4 For Emmy, holding and being held involves an oceanic feeling of connectedness across time and space: “We were so scared of drowning that we couldn’t see the difference between dissolving and allowing ourselves to be held,” writes Hulls: “It took writing this book to reconnect us to what we have always been. Mothers and daughters both damaged and saved by our imperfect love. Three women who have crossed so many oceans, trying to carry each other home.”5

: :

The sheer diversity of submissions we received for this cluster was difficult to narrow down into a feasible slate of essays. Ultimately, we wanted to centre a broad range of arts practices, and a diverse range of practitioners—a cluster that felt truly global, while not being too diffuse, and which retained a common sense of the characteristics of haunting in contemporary art. Of equal importance to us was the consideration that ghosts and haunting per se have radically different meanings dependent upon the culture and location in which they manifest—a New Yorker’s relation to a ghost is substantially culturally distinct from, say, that of a resident of Tokyo—so we wanted to present a series of essays that felt to us both global in nature, and also as if they were speaking to a specific shared cultural moment. The essays may be read in order, but they need not be—each haunts and is haunted by the others through a shared fascination with the ghostly.

The first four essays in the cluster consider haunting as an articulation of persistence and resistance in those displaced or persecuted. Nicole Dib’s essay ‘Of Haunts and Haoles’ approaches the work of contemporary Native Hawaiian writers, framing their writing as a response to land occupation, with the spectral becoming ever more present, the work moving from traumatic memory to full-blown apparitions. Arin Keeble and Jay Shelat’s ‘Jamil Jan Kochai’s “The Haunting of Hajji Hotak” and the Hauntology of the Forever War’ explores the effect of the War on Terror on the Californian Afghan diaspora and the population of Logar province in Afghanistan, and how Jamil Jan Kochai’s fiction approaches the successive generations lost to invasion and conflict as a process of haunting. Irina Troconis’s Of Frogs and Ghosts: Tales of a Haunted Diaspora’ considers the role of animals in the experiences of diaspora artwork, focusing particularly on the work of Venezuelan artist Paloma López, and considering how animals speak to and come to represent a ghostly form of displacement that echoes the lives of those transposed to another country or territory. Dorinne Kondo’s ‘Haunting as Atmospheric Violence’ argues that we can be haunted equally by “vibrations,” “toxicities,” “climate,” “weather” and, especially, “atmosphere”: “lingering affective histories” that “permeate the air, our skin, our unconscious”. Using Elaine Hsieh Chou’s 2022 novel Disorientation in the context of the recent spike in anti-Asian violence in America, Kondo argues that the ‘dis-orienting’ effect of historical Orientalism continues to haunt us well into the present.

The following three essays look specifically at American and British anti-Black racism, centring haunting as both a matter of recording and reckoning. George Kowalik’s ‘Past and Potential in Percival Everett’s The Trees’ uses Everett’s supernaturally inflected novel—which has as its motivating incident the racist murder of Emmett Till—and the work of Mark Fisher to think through the temporal looseness associated with haunting, and how the ghost might seek to avenge past injustices through the disruption of linear time. In ‘The Archival Haunt’, A. Banerjee goes via, the work of Saidiya Hartman and the poet Jay Bernard, into the archives of both transatlantic slavery and Black British life, thinking about how the archive as a resource can inform and build a concept of the archive as both resting place and site from which the past haunts us. M. Stang’s ‘Through the Eyes of the Sheet and by the Feet of the Ghost’ considers the stereotypical ghost costume—the sheet with eye-holes cut in it—as intertwined inseparably with the history of the Ku Klux Klan, and how the sheet has been used by the Klan to inflict a form of supernatural racial terror which is also bound up in the commercial image of Halloween and embedded in American culture.

The cluster ends with two essays that centre haunting in the aftermath of pandemics. Christine Prevas, in ‘Haunting Time and Space in All of Us Strangers’, takes Andrew Haigh’s acclaimed 2023 film, about a queer man haunted by the ghosts of both lovers and family, as a lens through which to consider the role of ‘queer time’ in contemporary haunting, and in particular its relation to the family and the home, in the context of the legacies of the AIDS pandemic. We hope that with this cluster can continue to develop the conversation around haunting in contemporary culture, locating it as a phenomenon that affords us a global view on the crises that attend us, and thinking through how spectrality might speak to our sense of a world that more than often feels always-already ghostly. As several essays in our cluster reflect, the notion of the “haunt,” especially in the noun form of that word, suggests the frequenting of some place, a hanging around or “hanging out” (cf. Sheila Liming). Bearing this locative sense in mind, the idea of a meeting (gathering of souls?), we intend this cluster of essays as a virtual haunt for present and future readers, a site to frequent, to come back to.

: :

Endnotes

- Jacques Derrida, Spectres of Marx: The State of the Debt, the Work of Mourning, and the New International, trans. Peggy Kamuf, with an introduction by Bernd Magnus and Stephen Cullenberg (Routledge, 1994), xix.

- Hulls’ memoir forms the basis of the Epilogue to Emmy’s forthcoming book, Filial Lines: Art Spiegelman, Alison Bechdel, and Comics Form.

- Tessa Hulls, Feeding Ghosts: A Graphic Memoir (MCD, 2024), 6, 10.

- Hulls, Feeding Ghosts, 352.

- Hulls, Feeding Ghosts, 378-79.