We are experiencing a witchy cultural renaissance. And no wonder: we are currently witnessing a violent global shift in conservative right-wing politics, the roll-back of reproductive rights, and overall rise in misogyny in the media—witches are rightly pissed off. In this essay, I consider how witches engage in a type of “spiritual algorithmic imaginary” on social media platforms such as TikTok.1 I draw on examples from my book Witch Power: Hexing the Patriarchy with Feminist Magic, which is about the power and potential of online hexes as a form of protest and a political response.

One of the targets of witchy rage is American far-right political pundit and misogynist Nick Fuentes, who tweeted the now infamous and vile “Your body, my choice.” His tweet enraged witches who took to social media to cast hexes on him. One TikTok hex that has over a million views shows a hex being performed on Fuentes that features the chorus Delilah Bon’s song “Dead Men Don’t Rape,” a ferocious punk and nu-metal song. There are some lyrics that come later in the song that embody the disruptive power that hexes represent:

Maybe it is and they’re scared we’ll discover

The strength of our feminine power

The strength of our anger in numbers

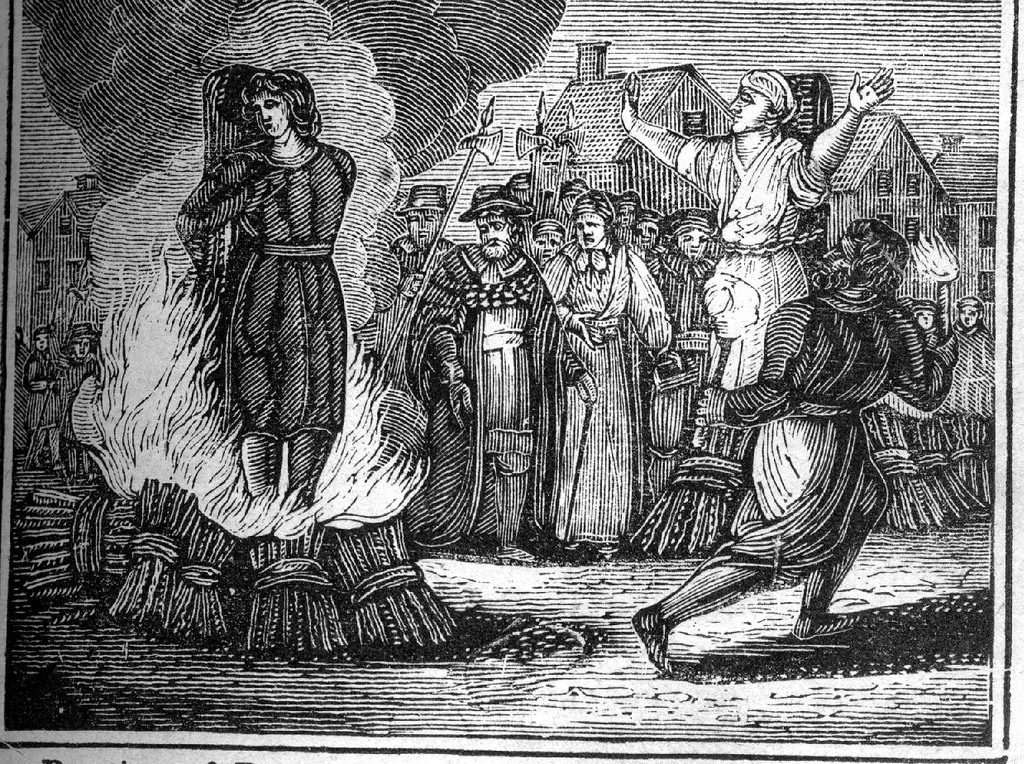

We are the witches they burned at the stake.

The popular symbol of the witch hunt—usually the woman burning at the stake—is invoked by both the far left (as seen in Delilah’s lyrics) and also by the far right as we can see in Nick Fuentes’s own words:

We need to go back to burning women alive. Like when they’re convicted of crimes obviously. Not-not random acts of violence. But remember that in medieval times I’ve said this on the show before. When women were witches, what happened to them? They were burned alive. Real phenomenon. And we stopped doing that and then everything went out of control.

There are strong historical precedents for political figures perverting the witch hunt trope for their own ends (McCarthyism being a prime example). During his first presidency, Donald Trump tweeted the words “Witch Hunt” more than three hundred times. While Trump uses the phrase to cast himself as a victim, Fuentes takes a slightly different approach. He conjures up a pseudo-nostalgic time (in a very MAGA fashion) where women were controlled through witch hunts to stop them from “speaking in devilish tongues and casting spells”—i.e., speaking freely and exercising any degree of social power. The key difference between them is that Nick is saying the quiet part out loud. When men talk about burning witches alive, what they are saying is that women need to be controlled.

In the lead-up to the 2016 elections in the US, a hex against Donald Trump went viral online. Originally created by Michael Hughes, thousands of witches both performed their own online and offline versions of the spell. It is important to pay attention to the materiality of these types of resistance rituals, that is to say, the artefacts and representations of things or people that they chose to incorporate into their spells. For instance, the spell Hughes created calls for an “unflattering photo of Trump” to direct the energy of the spell towards him. Other adaptations online showed people using other items to represent him, such as an orange candle, a carrot, or cheese puffs. The material “stuff” of religion can offer an insight into not only the types of beliefs in a religion or spiritual movement like witchcraft, but also the ideologies that these beliefs rest upon.

Take, for instance, the use of orange items people used in the spell to bind Trump. The use of orange items tells us that witches have a wicked sense of humor, clearly meant to poke fun at Trump’s fake tan. But making fun is not all that these witches were doing. Anthropologist Mary Douglas describes a specific type of comedy that relies not on the humiliation of another person but on countering control with something uncontrollable (like an internet meme) and thus triumphing over it.2 She argues humor is a type of social force that can be used subversively to challenge hegemonic forms of power. Humor and laughter can be powerful tools when it comes to social protest. But what is it exactly that witches are challenging with these types of political hexes?

Anthropologist Sabina Magliocco argues that types of “magical resistance emerged first from the religiously heterodox communities of modern Witches and Pagans, whose liberal, progressive, and universalist values were under direct assault by the president of the United States.”3 Echoing this sentiment, the originator of the binding spell stated that the spell was a response to a feeling of “creeping unease that Donald Trump’s use of nationalism, xenophobia, racism, and misogyny during his campaign would lead him to victory.” Uneasiness, uncertainty, and anxiety are emotions that have defined the past decade. On a reductive and more simplistic level, these spells could be seen as a tool for self-soothing during periods of social and political unrest. But I think this would be selling the potential and power of these types of rituals short. And it ignores the broader historical and political context of these spells of resistance.

While these types of spells are forms of political protest, the fact that they went viral reveals their other important role, as a social glue for people in times of division and uncertainty. Witchy author Pam Grossman writes about the power of “large public spells”:

I would offer that what public protest spells definitely do is build a sense of solidarity. Gathering in a group that has a shared goal reassures people that they are not alone, and that is consciousness-shifting in itself. Collective castings like these allow the disenfranchised to feel proactive and affirmed. They mobilize those who might otherwise be overwhelmed by despair, and they manifest catharsis and renewed strength. Group spells like these also put focus onto very real concerns about the dwindling safety of women, queer people, and people of color. Whether this magic “works” is subjective, it certainly amplifies the voice of resistance in its own cone of power.4

I like how Grossman responds to the question “Do these spells even work and if they don’t what’s the point?” with a resounding—who cares?Whether or not the spells “work” is not the point. These mass spells or hexes do work, but they do so socially—not magically.

: :

Hexes and Himpathy

Brock Allen Turner we hex you.

You will be impotent

You will know constant pain of pine needles in your guts

Food will bring you no sustenance

In water, your lungs will fail you

Sleep will only bring nightmares

Shame will be your mantle.

You will meet justice.

My witchcraft is strong.

Our witchcraft is powerful.

The spell will work.

So Mote it be.

The spell above was part of a hex that was shared widely on Facebook in 2016 during the trial of Stanford University student Brock Turner. The hex was organized by Melanie Elizabeth Hexen, a midwife who lives near Wilton, Iowa. In an interview with Vice, she explained that her local coven, made up of thirteen women, was motivated to create the hex after feeling “outraged and helpless” over Turner’s short sentence.

Soon after the Facebook event was created, more than 600 people RSVPed. Witches participated from various regions of the US as well as internationally, hexing-in from countries like Peru and Uruguay. Some of those who participated anointed their candles in urine or menstrual blood, and many incorporated sulphur or salt circles into their ritual. The witches deliberately layered forms of socially defined “dirt” and filth, like menstrual blood, and literal shit (one witch used their neighbors’ dog’s fecal matter) to drive home the message that Turner is a piece of (socially categorized) shit.

Many of those who participated in the hex were survivors of sexual assault themselves. They posted their own experiences in the Facebook event, sharing their solidarity and support for one another. In her interview with Vice, Hexen expressed her deep gratitude for those who joined in:

I was touched so deeply they were involved in this ritual, and I feel that their witchcraft was ten times more powerful than mine in this situation. Someone who has been through something like that would have so much rage and so much power and so much need for justice that they made it so much stronger. It was brave of them to come forward and hopefully cathartic for them to do that.

The biggest difference between this ritual and the one cast on Trump is the intention. While the spell on Trump was more passive and meant to bind him from doing harm to others, the hex on Turner was designed to cause him harm—or make him “impotent.”

Emasculation and castration: what a wicked combination. The hex invokes not only the fear of castration, but the legacy and mythology tied up in the figure of the witch as one who disrupts the broader social order. It’s a creative play on some old sexist notions. But what are the social structures that witches are attempting to disrupt? Philosopher Kate Manne explains that “misogyny is not about male hostility or hatred toward women—instead, it’s about controlling and punishing women who challenge male dominance.” Misogyny rewards women who reinforce the status quo and punishes those who don’t. Sexism, on the other hand, is the “ideology that supports patriarchal social relations, but misogyny enforces it when there’s a threat of that system going away.” Turner and Trump are a product of both sexism and misogyny.

Both Turner and Trump benefit from what Manne calls himpathy, which she defines as “the disproportionate or inappropriate sympathy extended to a male perpetrator over his similarly, or less privileged, female targets in cases of sexual assault, harassment, and other misogynistic behaviour.” She gives the example of the treatment of Brett Kavanaugh during the Senate Judiciary Committee’s investigation into allegations of sexual assault leveled against Kavanaugh by Professor Christine Blassey Ford. Manne points to the public’s praise of Kavanaugh as a brilliant jurist who was being unfairly defamed by a woman who sought to derail his appointment to the Supreme Court of the United States as an example of himpathy in action. Himpathy shields perpetrators like Kavanaugh by positioning them as “good guys” who are the victims of “witch hunts.” Kavanaugh, unsurprisingly, was also a target of mass hexes organized online.

After his inauguration in 2017, Donald Trump tweeted the words Witch Hunt roughly once every three days during his first presidency. Through the act of identifying himself as the victim of a witch hunt, Trump was able to condemn the charges against him as not only improbable, but impossible. Witch hunts are, by their very nature, illegitimate, their victims innocent, their judgements always wrong. Understandably, his use of this phrase has angered many witches. For instance, Ann Hardman, a Louisville high priestess in the Fellowship of Isis said that “it conjures up for me the burning of 10,000, mostly women, in England . . . who were accused as witches—right out of the Inquisition playbook.”These types of arguments against Trump using the “witch hunt” often end up erasing the witch hunts that are currently happening around the world today.

This erasure is deliberate and necessary for the narrative to retain its potency and political punch—so that men like Trump and Kavanaugh and Turner are the victims of false accusations. Victims of cancel culture. Victims of hysterical mobs. Victims. This narrative is both powerful and pervasive, requiring people to rise up and challenge it from multiple fronts. For witches, hexes represent a similarly potent form of political protest and resistance when it comes to combating the rise of misogyny in the world today. Performing these rituals of resistance online and having them go viral symbolises the power of hexes, to be able to harness and channel the power of the algorithm.

: :

Endnotes

- Sara Reinis and Corrina Laughlin, “GOD IS MY SPONSORED AD!! MY ALGORITHM!”: The Spiritual Algorithmic Imaginary and Christian TikTok,” New Media and Society (2025).

- Mary Douglas, “The Social Control of Cognition: Some Factors in Joke Perception,” Man 3, no. 3 (1968): 361–376.

- Sabina Magliocco, “Witchcraft as Political Resistance: Magical Responses to the 2016 Presidential Election in the United States,” Nova Religio: The Journal of Alternative and Emergent Religions 23, no. 4 (2020): 43–68.

- Pam Grossman, Waking the Witch: Reflections on Women, Magic, and Power (Simon & Schuster, 2019).