Save the hug of the chosen

the travel album

the books

save the song of the frogs

at night.

— Alida Ribbi, “Las velas del tiempo”

: :

I.

Animals of all kinds dwell in the memory and find shelter in the work of writers, artists, and filmmakers who attempt to put into words and images the pain of what Gustavo Guerrero, echoing Hannah Arendt, calls “Worldlessness”: a loss that results from experiences such as persecution, deportation, and exile that isolate us from others, “depriving us of our interlocutors and our familiar references, tearing us away from the community fabric that had fully recognized our legal rights and throwing us into a foreign territory.”1 In a verse from her poetry volume Lugares abandonados: Antología personal (2018), Venezuelan poet and critic Gina Saraceni writes: “Partir es un animal que muerde.”2 Leaving one’s home behind, departing one’s country, is—she says— “an animal that bites.” In a different poem that also speaks about the pain of migration, displacement, and exile, titled “Home,” Somali British poet Warsan Shire writes: “No one leaves home/unless home is the mouth of a shark.”3 Biting the corners of Julio Cortázar’s world-renowned novels are the eleven, pocket-sized bunnies that the narrator of his short story “Letter to a Young Lady in Paris” throws up after he moves to a friend’s apartment to get some rest, a move that, however short-term, changes something inside him, making him come to terms with the naked horror of being in a place that was not unfriendly but that was also not his own, that was harmless but that would ultimately destroy him.4

It makes sense that animals are there, among the exiled and the displaced evoked in these fictions. After all, dragged away from their own homes to occupy space on a page or on a screen, they are always already “singular lives orphaned from their holobiomes.”5 A such, they often serve as metaphors and symbols for the loneliness and the nostalgia that mediate experiences of displacement, the “terrible lightness of their being,” in Anat Pick’s words, made heavy by the many meanings animals, in the peculiar intimacy of their silent otherness, can hold.6 This silent otherness renders their presence uncanny not only in scenarios of displacement, like the ones mentioned above, but in any human landscape, which has led a number of scholars to compare animals to ghosts.

For instance, in his introduction to Ghost, Android, Animal, Tony M. Vinci defines animals as “the radically embodied life outside of human language” and ghosts as “the disembodied voice, the present non-presence,” and argues that “the animal is always already ghost in its presence in human bodies and texts.”7 While Vinci reads in this becoming ghost of the animal a new type of engagement with “historical events, lived experience, and the speculative realities of the unknown,”8 there is also loss and a certain degree of violence in it that risks turning the search for a posthumanist form of relationality into yet another way in which the animal is rendered powerless and inferior to the human. This is partly because the transformative potential Vinci and other scholars of the ghostly—such as Avery Gordon and Jacques Derrida—see in the ghost is intrinsically tied to the ghost’s ability to, sooner or later, speak. In fact, Derrida ends Specters of Marx, a seminal work of the so-called “spectral turn,” by noting that, if he loves justice, the scholar of the future “should learn it from the ghost. He should learn to live by learning not how to make conversation with the ghost but how to talk with him, with her, how to let them speak or how to give them back speech.”9 To give the ghost back speech requires the ghost having it in the first place, an assumption that is difficult (if not impossible) to make when it comes to animals.10 Without it—without a translation into human language that necessarily erases something about “the ‘stuff’ of animal nature” as it strives to give the animal ghost “back” its speech—what power could the animal, conceived as a silent ghost, possibly have?11 Taking this question as a point of departure, what follows is an exploration of what it means to not read the animal as a literal or metaphorical ghost. This provocation offers an opportunity to engage with that unsettling encounter with an animal that resists anthropocentric operations of resignification, an encounter that was famously theorized by Derrida when he found himself naked in front of his (equally?) naked cat Logos, and that Mel Y. Chen returns to in Animacies as they attempt to answer the question: “What happens when animals appear on human landscapes?”12 I will analyze this encounter as it takes place in Venezuelan director Paloma López’s short film Home (2023), a film that belongs to the corpus of cultural production emerging about and from the Venezuelan diaspora.

As of 2024, more than seven million Venezuelans have left their country in what is now the biggest migration wave in the modern history of both Venezuela and the Latin American continent. Home stages this encounter with the animal in an apartment filled with all the belongings of a family that had to leave their home in Caracas and start over across the Atlantic, in Paris. I will argue that, in that space which brings together the familiar and the unfamiliar, the foreign and the national, the presence of the animal—the unexpected presence of hundreds of frogs, to be exact—makes the human characters vulnerable to the reality that the fictions they most desperately hold on to (fictions of belonging, fictions of origins, fictions of home) have cracks, and that in those cracks, there is something that they missed, something that they forgot and that, in its unfurling, promises to scatter them from within. Ultimately, I will propose that the refusal to read the frogs as ghosts (and the frogs’ own resistance to that reading in the film) exposes the ghostliness of the human protagonists themselves, a ghostliness that does not have to do with the presence/absence of the dead that haunt the living, but rather with the affective experience of being away from home, surrounded by numerous, heavy belongings, and nevertheless feeling short of history.

: :

II.

Home is the story of a Venezuelan family that moves from Caracas to Paris along with their belongings, which, they soon discover, are more than the space in their new apartment can hold. The night before their things arrive wrapped in plastic, the four members of the family—father, mother, and two daughters, of which only the mother and one of the daughters have a recognizable Venezuelan accent—sit in the empty apartment, and Clara, one of the daughters, tries to teach the rest of the family a tongue twister in French. Josefina, the other daughter, sits quietly, refusing to participate, and then moves to a different room to call her ex-girlfriend in Caracas.

Before we hear the girl’s voice on the other side of the call, we hear the frogs, and not just any kind of frogs, but the coquí. Named after the distinctively loud call the males make at night (co-qui), the coquís’ song has become a fixture in Caracas’s soundscape, often alluded to in works of Venezuelan fiction that speak nostalgically of the home left behind, such as Alida Ribbi’s poem “Las velas del tiempo.”13 The coquís, however, are not native to Venezuela but to Puerto Rico and the Antilles. The invasive species arrived in Venezuela (and other South American countries) presumably in the 1950s and found a home in many neighborhoods in Caracas and in other cities all over the country.

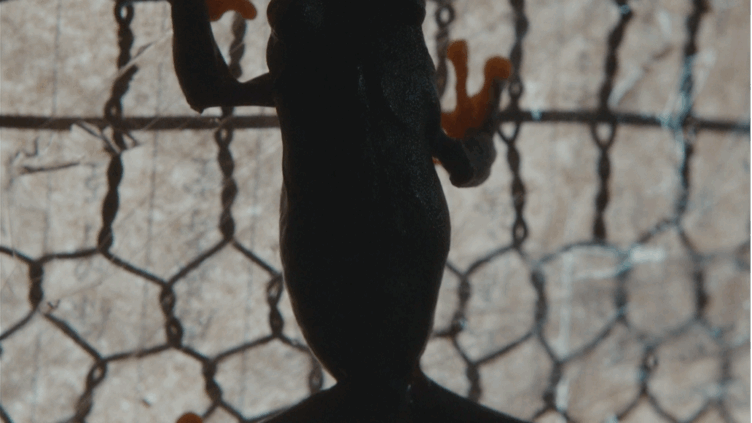

The morning after Josefina’s call, the family receives their furniture and creates a voting system to decide which objects to throw away and which to keep. Josefina’s old green wardrobe is the first one the other family members vote to get rid of, which causes her to accuse them of rejecting anything that is old or ugly, and, to prove her point, she “makes herself ugly” by cutting her face with a knife. She then sits among the furniture and starts wrapping her body in plastic when, suddenly, she hears and then sees a small green frog—a red-eyed tree frog, not a coquí. She shows the frog to her sister Clara, and when it jumps off her hand, Clara steps on it and kills it. Many more frogs appear then, taking over every inch of the apartment, driving the parents mad until they finally call the exterminators (Figure 2). The last shot of the film shows the family walking together in an empty street in Paris and, hiding inside Josefina’s fist, a live frog, its red eyes looking straight at the camera (Figure 3).

Though the story Home tells certainly stands on its own, the film also captures the “afterlife” of the over two hundred objects that, wrapped in polyethylene film, make up the installation Crisálida (chrysalis) (Figure 4), by Venezuelan artist Pepe López, Paloma López’s father. Originally shown at Espacio Monitor, Caracas, in October 2017, Crisálida was described by curator Miguel Miguel García as “the biggest, most compelling and most significant monument created until now in honor of the Venezuelan diaspora,” a diaspora that, as of 2024, encompasses more than eight million Venezuelans.14 What made Crisálida so impactful, as many critics have argued, is its liminality: the way it captures neither the moment of arrival, nor the moment of departure, but the pain that comes with the decisions that every person who has ever had to leave home knowing they might never come back has had to make: what to leave and what to take; whom to leave and whom to take.15 Wrapped in plastic, the objects in the installation are suspended, practically useless; and yet, it is precisely because of that lack of practical functionality that they can protect and preserve the memories attached to them.

After Crisálida was exhibited in Caracas and then in London’s Fitzrovia Chapel in 2018, the objects—which actually belonged to Pepe and Paloma López and had been in their house in Caracas until the family had to leave the country—became homeless, impossible to store in art galleries and impossible to fit in the López’s new apartment in Paris. Home takes that moment the objects arrive and demand to be dealt with and, rather than showing us which of them made the cut and which of them were discarded, further complicates the question by introducing an animal that has been there, it seems, all along, growing in a chrysalis that, promising a butterfly, birthed instead a frog. And not just any frog, but the wrong kind of frog.

: :

III.

A frog that is not a coquí frog but that sounds like it. A coquí frog that sounds like Venezuela but that is not Venezuelan. A father and a daughter who are, presumably, Venezuelan, but whose accents sound like Honduras (the father) and Spain (Clara). These elements of the film, which speak of animals, sounds, and people that do not quite fit, are easy to overlook as the story develops and we focus on “the bigger picture.” However, if we choose to linger on them, to notice how they puncture Home’s smooth surfaces and narrative, they become not only the stitches that the film proudly displays rather than hides and that speak of the material conditions of its production, but also evidence of the often subtle and always violent transformations an identity undergoes as bodies engage in the act of making a home outside of home.

The inclusion of a Honduran and a Spanish actor in lieu of an all-Venezuelan cast points to the reality that there might not be that many Venezuelans—or at least, not that many Venezuelan actors—living in Paris, a fact that responds, among other things, to the immense economic privilege that would be necessary for people in Venezuela to migrate and settle in the European capital. Similarly, the presence of the red-eyed tree frogs is a consequence of the difficulty of finding coquí frogs in Paris—a species that has for the most part stayed (though not still) on the other side of the Atlantic. That Home does not fix these limitations through Photoshop (for the frogs) or sound alteration and accent training (for the actors) allows them to become loud reminders of what it means, really, to make a film about a Venezuelan experience outside of Venezuela: to remember and re-produce sounds that, being removed from the environment that created them and the bodies that make them, cannot ever be as they were, but must change, adapt, and become something else, something that ends up being at once familiar and unfamiliar.

Memory is, after all, “a matter of hearing.” As Saraceni points out, “[i]t is not possible to remember except within a language, and memory is the way that language sounds . . . To remember is a sound that is heard, a verbal material that the memory solicits so that the murmur of the past unfurls.”16 Home insists on this understanding of memory from the very first scene, which shows Clara teaching her family a French tongue twister that emerges as the sound coming from the future—a future where the family has adapted to their new life and mastered the specific sounds of the French language—and which finds its counterpart in Josefina’s call to Caracas in the following scene, where we hear, and not only hear but see her remember, the call of the coquí, louder than the voice of the girl on the other side of the phone call. In this scene, the sound is still, technically, located in Caracas, and while we do not see them, we can imagine the coquí frogs that make it “all the way over there.” However, when the sound arrives to Paris along with the family’s belongings, when it materializes in the body of the frog, it allows for what Cecilia Macón calls “a transtemporal mode of contact involving past, present, and future” that produces a noise that is “off-key,” not because the sound itself is the wrong kind of sound, but because it is being made by the wrong kind of body.17

This friction between sound and body, this “relocation gone wrong” that we can also hear in the “wrong” accent of the presumably Venezuelan characters, allows us to interpret Clara’s stepping on the red-eyed tree frog as something besides a feature of her increasingly violent and authoritarian character. Is Clara killing the frog simply because she wants to hurt Josefina, or is she killing it because it was the wrong frog making the right sound? Put differently, must the frog disappear because it embodied a memory that refused to stay where it belonged—in the past, over there—and appeared, like an accidental invocation, over here, to hijack the family’s determination to move on? And, had it been a properly Venezuelan coquí frog, would she have let it live then, as a relic, a souvenir, a perfect replica that would complement all the perfectly preserved objects? Whatever the answer, it would not matter. Killing the frog, violently marking the separation between “before” and “now,” “there” and “here,” by eliminating the uncanny body that overlapped them, did not stop more frogs from crawling out of the wrapped belongings, disturbing their preserved stillness while taking over the apartment and, in doing so, proving to the family that many things can fit in the forty-five meters that mark the apartment’s perimeter, especially if those things are things that they forgot or wanted to forget.

As such, the frogs show the limits of the illusion we have of controlling which elements of our (national, collective, individual) identity we consciously choose to take with us when we leave our home behind, and the often-unexpected transformations they suffer when removed from their original environment. Amidst an ever-growing corpus of diasporic fictions that fixate our attention on suitcases and backpacks and the care and pain that go into deciding which objects to put in them and which to abandon, the unexpected presence of Home’s frogs alerts us to the possible existence of things we did not know we packed: things that came with us without our permission and that, though familiar, and even longed for, when relocated, do not provide a sense of comforting belonging but instead mutate and inconveniently demand to be reckoned with. And reckoning with them, in the case of Home, means dealing with the fear, the madness, and the violence that do not find a place neither in nostalgic reconstructions of the experience of leaving one’s home behind—a nostalgia that resembles what Svetlana Boym calls “restorative nostalgia” and that in the film appears associated with Josefina—nor in narratives that would exclusively focus on smooth adaptations and quick transitions, like the one desired by Clara and the parents.18 The hundreds of red-eyed tree frogs, ill-fitting, create an atmosphere of haunting where what haunts are not the ghosts of the dead, but, in Avery Gordon’s words, “something lost, or barely visible, or seemingly not there to our supposedly well-trained eyes.”19 Something that shows up unexpectedly, unapologetically, to meddle with “taken-for-granted realities.”20 Something that, in case of the characters, draws their attention toward the imminence of moments of misrecognition and (un)belonging that await them in their new “home” and the possibility they open to remember, not in the sense of recovering a lost past or completely forgetting about it, but “as a critical way to refuse a for-granted continuity of the same.”21

: :

IV.

Though all animals could be read as ghosts—as noted earlier, animals, for some, are “always already ghost” in their presence in human bodies and texts—frogs seem to be uniquely ghostly. They appear to us as liminal, their bodies half-submerged in bodies of water, which has made them ideal representations of the afterlife and the underworld.22 They are also often heard before they are seen, their loud calls making them a distinctively sonic creature, and sound, as Ana María Ochoa Gautier and Juliana Martínez remind us, is closely tied to the spectral.23

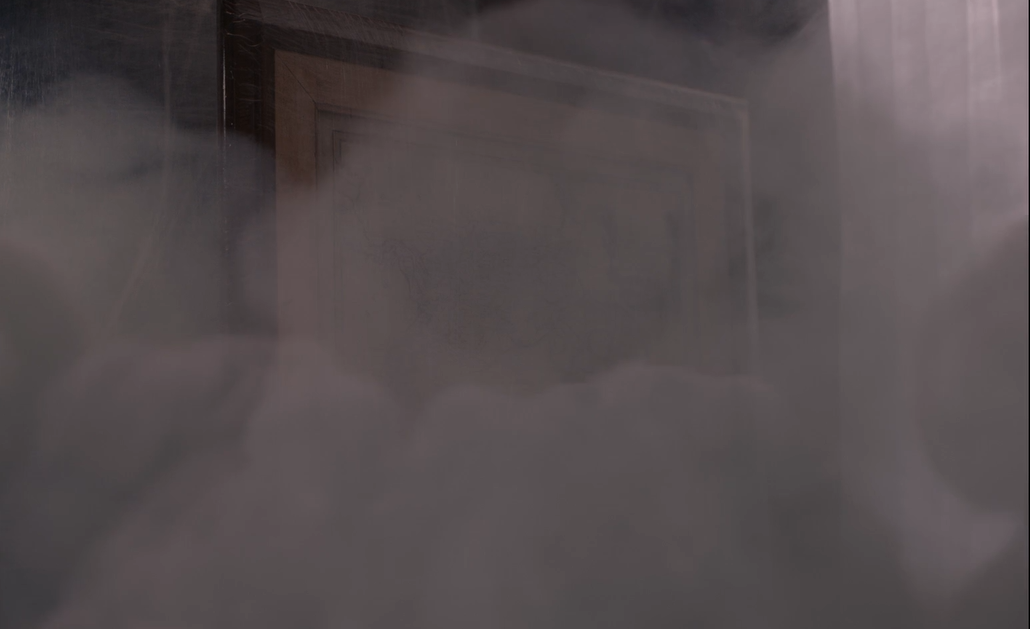

And yet, the frogs from Home are not ghosts, however tempting it would be to read them that way. Not only is their appearance in the film’s plot within the realm of possibility,24 but the brightness and liveliness of their colors (red and green) contrasts with the faded colors of the apartment, the objects wrapped in plastic, the translucent curtain that appears repeatedly in the middle of the shots, and even the clothes of the parents, the brown and beige hues of which allow them to easily blend in with the furniture (Figure 5). This faded aesthetic is the product of a chemical process called bleach bypass, a process that López performed digitally and that superimposes a black-and-white image over a color image. The resulting images usually have reduced saturation, increased contrast, and graininess.25 The process of creating the film’s images and the aesthetic they produce thus turn the apartment into a ghostly space that is noticeable as such precisely because of the saturation of the frogs, understood both in terms of their color and in relation to their invasion of the apartment. It is thus not the frogs that are the ghosts of Home: the ghostly is in everyone and everything surrounding them. And, rather than serving to bring the ghostly place and the people in it “back to life” the way nostalgia imagines the lost past, if recovered, would, the omnipresence of the frogs underscores the paradox of having so many things that speak of the heavy weight of a history—a familiar, individual, collective, and national history represented by lamps, paintings, bedframes, etc.—and nevertheless being, in this foreign place they have to call home, what Omar Kasmani calls “short of history,” which means to no longer have narratives to inhabit, to have no clear way (anymore) of “being and belonging in time.”26

This realization becomes pressing toward the end of the film, when the smoke coming from the exterminators’ machines visually erases the family’s belongings (Figure 6), and the camera switches to show the parents and the daughters walking together, quietly, on an empty street—like ghosts. In the last shot, Josefina appears holding in her hand the only survivor of the frog massacre, its red eyes peeking out of the fist being the last thing we see, and the last thing that sees us (Figure 7). The frog’s survival could be read as the survival of memory, the sound it holds within constituting the acoustic and ghostly remnant of the Caracas the characters might never see again. This reading would be yet another example of the many ways in which “animals are overdetermined within human imaginaries.”27 Instead, I propose that we read that frog, not for everything it could be and mean, but for what it actually is: a displaced animal, a creature that is not where it is supposed to be, an involuntary actor in a story that ended up being its own story. Its silence—for the first time in the film, the frog is not singing—stages an encounter with “countless worlds of perception which are forever closed to us,” and as it fuses with the silence of the family members, it creates a commonality, a something shared between them that reframes this new chapter of their life not in terms of nostalgia, adaptation, or forgetting, but in light of what it means to live with the unsaid: with that which escapes knowledge and which escapes us.28 That which does not need translation. A mode of living that can be a painful shortcoming, but that can also be an opening toward finding belonging somewhere beside or beyond clear narratives of origin, and the comfort (and the violence) of what is familiar and familial.

: :

Endnotes

- Gustavo Guerrero, “Between Fire and Ruins: Migrant Versions of Contemporary Venezuelan Poetry,” Review: Literature and Arts of the Americas 54, no. 2 (2021): 173.

- Gina Saraceni, Lugares abandonados. Antología personal (Editorial EAFIT, 2018), 36.

- Warsan Shire, “Home,” in When Home Won’t Let You Stay: Migration through Contemporary Art, eds. Ruth Erickson and Eva Respini (The Institute of Contemporary Art/Boston and Yale University Press, 2019), 29.

- See: Julio Cortázar, “Carta a una señorita en París,” in Carta a una señorita en París y otros cuentos (Editorial Sevillana, 1994).

- Jens Andermann, Entranced Earth: Art, Extractivism, and the End of Landscape (Northwestern University Press, 2023), 191.

- Anat Pick, “Ghosts at a Glance: Four Animal Fragments,” in Feeling Animal Death: Being Host to Ghosts, eds. Brianne Donaldson and Ashley King (Rowman & Littlefield, 2019), 230.

- Tony M. Vinci, Ghost, Android, Animal: Trauma and Literature Beyond the Human (Routledge, 2019), 19.

- Vinci, Ghost, Android, Animal, 20.

- Jacques Derrida, Specters of Marx: The State of the Debt, the Work of Mourning and the New International, trans. Peggy Kamuf (Routledge, 2006), 221.

- This is not to say that animals do not communicate or have their own language. As Chen demonstrates in their chapter “Queer Animality,” research in linguistics and other areas has found ample intelligent language use in many animal species. I am rather highlighting the loss (of agency, of alternative epistemologies) that necessarily occurs when animals are conflated with human ideas about what animals are, mean, or say.

- Mel Y. Chen, Animacies: Biopolitics, Racial Mattering, and Queer Affect (Duke University Press, 2012), 89.

- Chen, Animacies, 89. On Logos, see: Jacques Derrida, The Animal That Therefore I Am, ed. Marie-Louise Mallet, trans. David Wills (Fordham University Press, 2008).

- Alida Ribbi, “Las velas del tiempo,” in El puente es la palabra. Antología de poetas venezolanos en la diáspora, comp. Kira Kariakin and Eleonora Requena (Caritas Venezuela, 2019), 110.

- “Obras recientes de Pepe López en Escape Room.” Tráfico Visual, January 1, 2017. https://traficovisual.com/2017/11/01/obras-recientes-de-pepe-lopez-en-escape-room/

- See Tamara Chalabi, “Enduring Ephemeral,” in Crisálida, ed. Tamara Chalabi (Ruya Maps, 2018), 7-16.

- Gina Saraceni, “Inheritance in the Mother Tongue,” Latin American Literature Today 15, 2020, https://latinamericanliteraturetoday.org/2020/08/inheritance-in-the-mother-tongue-gina-saraceni/

- Cecilia Macón, “Haunting Voices: Affective Atmospheres as Transtemporal Contact,” in The Affect Theory Reader 2, eds. Gregory J. Seigworth and Carolyn Pedwell (Duke University Press, 2023), 350.

- See Svetlana Boym’s chapter “Restorative Nostalgia: Conspiracies and Return to Origins,” in The Future of Nostalgia (Basic Books, 2001) 41-55.

- Avery Gordon, Ghostly Matters: Haunting and the Sociological Imagination (Minnesota University Press, 2008), 8.

- Gordon, Ghostly Matters, 8.

- Omar Kasmani, “Migration: An Intimacy,” in The Affect Theory Reader 2, eds. Gregory J. Seigworth and Carolyn Pedwell (Duke University Press, 2023), 216.

- See for instance the appearance of frogs in Jayro Bustamante’s film La Llorona (2020) and in Ancient Greek playwright Aristophanes’s comedy The Frogs (405 BC).

- See: Ana María Ochoa Gautier, Aurality: Listening & Knowledge in Nineteenth-Century Colombia (Duke University Press, 2014), and Juliana Martínez, Haunting without Ghosts: Spectral Realism in Colombian Literature, Film, and Art (Texas University Press, 2020).

- I thank Paloma López for pointing out to me that, while extremely unlikely, it was not entirely impossible for frogs to indeed reproduce among the belongings as they traveled by boat from Venezuela to France. During our conversation about Home, she argued that this minuscule possibility was central for the conception of the film, which was not imagined as an example of magical realism.

- I thank Paloma López for alerting me to the use of this technique in the editing of Home.

- Kasmani, “Migration: An Intimacy,” 217.

- Chen, Animacies, 90.

- Ruth Heholt and Melissa Edmundson, “Introduction,” in Gothic Animals: Uncanny Otherness and the Animal With-Out, eds. Ruth Heholt and Melissa Edmundson (Springer International Publishing, 2020), 7.