Despite our love for a classic ghost story, we know that some figures outside the category of easily registered phantoms can haunt us more than a typical specter. For those arts of the present whose creators were and are historically vulnerable to attempted disappearance, active silencing, and other violent actions, the representation of more atypically haunted scenes can disquiet readers and remind them of other sinister narratives that might more easily take center stage. In terms of the present, Native Hawai’i has fought back against the specter of attempted disappearance via hostile takeover and continued land occupation, and continues to resist the non-presence that American media so easily slips into when it comes to Native voices on the islands. To foreground the role that haunting images, stories, and motifs play in this constant battle, we can understand Kānaka Maoli depictions of these scenes as resistant moments, while also turning an eye to a different and dreadful kind of haunting that emerges in non-Native Hawaiian scenes and stories.

Here lies the haunt for Hawai’i—the continued presence of threatened non-presence, tangible in political attempts at silencing and legible in conspicuous absence from mainstream media. Native Hawaiian authors write back against this threat in numerous forms, and the short story collection emerges as a unique space where ghosts can play through the pages of connected but separate tales. Published ten years apart, Kristiana Kahakauwila’s 2013 This is Paradise and Megan Kamalei Kakimoto’s Every Drop Is a Man’s Nightmare (2023) are contemporary collections that reveal the specter of settler colonialism that, by its very nature, refuses to depart. Both short story compilations enact the writing practice and encourage the reading process that Brandy Nālani McDougall describes when recollecting the family stories passed to her from her grandmother; these were enlivening, cautionary, didactic, and often spooky, and they help create the practice of “kaona connectivity” which McDougall traces in the ability for contemporary Hawaiian literature to “carry and elicit ancestral memory, empathy, and various forms of cultural sovereignty.”1 The last facet of this connectivity is especially important for the fight against colonial transgressions that continue to haunt the Hawaiian islands and their Indigenous inhabitants. In the short fiction pieces by Kahakauwila and Kakimoto, we can trace different forms of haunting that emerge in actual apparitions as well as less overtly supernatural displays of haunting like memories. I read these together with other scenes of on-island haunts that represent the lingering presence of colonial violence, a presence that fiction can combat—we will see how fiction’s vocality becomes a site on which colonial silencing is rejected.

The Kānaka Maoli presence that Kahakauwila and Kakimoto’s short stories foreground and the haunted nature of their fictional tales emerge in contrast to a still-present, still ghastly effort to erase the Native Pacific from the Pacific. We can unbury sometimes lesser-known haunted histories, such as the 12-year-long period in the mid-twentieth century when the U.S. detonated nuclear weapons on the Marshall Islands—from this period of aggravated assault in the pursuit of nuclear arms came the now ubiquitous bikini, named after the atoll reef on which nuclear weapons were dropped. It is one of the first contested images in Kahakauwila’s titular “This Is Paradise,” revealed when the surfer girls who partially narrate the piece notice how a doomed tourist (who the story tracks) “wears a white bikini with red polka dots. Triangle-cut top, ruffled bottom” in comparison to their “carefully cut pieces with cross-back straps and lean bottoms” for surfing.2 Read in this light, the aesthetic of (certain) bikinis and the tourist class they stand for rises from the grave of environmental destruction and displacement of Indigenous Marshallese people; as Teresia Teiawa explains, “In a tourist economy, the beach becomes the principle site of leisure—and a cliched backdrop for bikini-clad tourists.”3 Jessica Hurley notes in her analysis of nuclear colonialism in the Pacific that “The nuclear ghost, like other ghosts, figures time out of joint,” and that Indigenous filmmakers such as the Marshallese Kathy Jetn̄il-Kijiner have created decolonial works that engage with, rather than attempting to banish, these ghosts.4

As part of her affirmation of continued presence of people, stories, and specters, Kakimoto’s stories often feature haunting on two scales of the narrative—in the larger scope of the plot, and within seemingly sidelined reflections. In the second, titular story of her own collection, a girl named Sadie and her parents drive the old Pali highway to a family barbecue, encountering a puaʻa, a wild pig that Sadie notices is bleeding profusely.5 On their way back home, they tempt rotten luck by driving leftover pork back home with them over the Pali, an image of which introduces this essay: “It is the most haunted road on the island, a two-lane highway where atrophied asphalt unfolds over the bones of dead ancestors, from makaʻāinana like her own late kūpuna to aliʻi as revered as Kalanikūpule himself. Descending from windward O‘ahu to the bustling hub of Honolulu, the road hooks around the contours of the Koʻolaus, and it is in this place of transition where things start to get interesting”6 Reflective, history-making lines like this one affirm the presence and the haunted nature of iconic locations such as the Pali highway. Kakimoto’s collection opens with a three page piece called “A Catalogue of Kānaka Superstitions, as Told by Your Mother” that advises what not to do while driving over the Pali (and, which warns against drawing the attention of the Night Walkers, who make an appearance later in the collection)—the throughlines between her stories affirm the contemporary presence of Native Hawaiian beliefs, as well as the continued presence of haunted locales that are decidedly not devoid of Kānaka inhabitants and travelers.

In part because of their throughlines, what short stories can distinctly do is drop readers into scenes, interactions, and incidents without needing the scaffolding of a larger narrative. Stories like the ones in Kahakauwila’s This Is Paradise give evocative snapshots, lingering with us perhaps even longer because of how brief they are. The first story in her collection, “This Is Paradise,” is narrated in the first-person plural and shifts between three groups of Hawaiian women—surfers, high-level careerists, and hotel housekeepers—all watching one white woman tourist who pops in and out of their day. When the surfer women’s narrative voice explains that this tourist, Susan, looks like any other, but asks “So why do we look at her as we pass? Why do we notice her out of the hundreds of others? Do we already know she’s marked, special in some way?,” readers’ curiosity and perhaps fear is piqued.7 As the story progresses and covers the daily lives of these three groups of women, who occupy differently unique roles in the Waikiki-adjacent cityscape, the tourist moves toward her deadly fate. She is murdered by a man who picks her up at a bar, a scene partly witnessed by the surfers who mourn her in their own way: “We sit on our boards and form a tight circle, our knees bumping into the rails of the boards on either side of us, and we pule, we pray. We ask for forgiveness. We ask for patience. We ask for guidance, not only for our lives but for Susan’s family, and for the island.”8 Although this story does not have elements of the supernatural, it is haunted by the specter of sexual assault and deadly violence that women (particularly Indigenous women) are susceptible to. The surfers’ prayer is a coming to terms with the constant threat of this violence, a moment of Kānaka speaking back to and against a contemporary, colonial, repeated scene of violence. And while there is no immediately spectral presence, the story tracks a day in the life and death of a tourist through the local’s eyes in a way that is haunting on a metaphorical level, and that imbues the brief narratives of the collection with a sense that the boundaries between the living and the dead will be easily traversed.

In a similarly more metaphorically haunted tale, the closing story of This Is Paradise titled “The Old Paniolo Way” follows a Native Hawaiian man named Pili as he returns to the Big Island from his expatriated home of San Francisco in anticipation of his father’s death. His father, the “old paniolo” (a Hawaiian cowboy) is not aware that his son is gay, and the deathbed setting seems like a chance for Pili to come out and thus prevent the haunting of his own future by the specter of his father’s ignorance. Kahakauwila’s story, however, disrupts several facets of normative expectations for queer people of color narratives. Stephanie Nohelani Teves’s articulation of Pili’s haunting (un)freedom in San Francisco compared to his homeland is critical here: “For queer Natives, leaving home might provide freedom from the colonial imposition of heteronormativity in their communities, where it has taken on the semblance of being natural, rather than a missionary introduction, such as in the case of Hawai’i.”9

Teves’ formulation invokes the specter of colonialism and considers how it changes typical readings of the “coming-out” arc of Kahakauwila’s story, a reconsideration that does refuse the standard closure of these tales (whether this closure is acceptance or rejection): Pili’s refusal to “come out” in a “traditional” way to his dying father, argues Teves, “reminds us that the feeling of belonging and welcome at the end of the story becomes possible only through the practice of aloha where family and kin networks, genealogies, and working together are prioritized over the self.”10 This reading, invoking Kānaka Maoli worldviews, redirects the ending away from a haunting lack of closure and toward a different closure legible through the Native Hawaiian ethos that Kahakauwila’s story invites readers to learn about.

These worldviews, connected always to different haunts, also appear in Every Drop Is a Man’s Nightmare, particularly in Kakimoto’s perhaps self-referential story “Aiko, the Writer,” who has “bent to readerly expectations of an Indigenous writer” by writing about the Night Marchers—they were invoked earlier in her collection as the terrifying ghosts of deceased Hawaiians who can be summoned by whistling at night, among other acts.11 The horror of this story unfolds with attention to the act of writing about such haunted matters; Aiko’s TūTū Gracie, her mother’s mother, warned her that “There are ways to tell Hawaiian stories and ways to make Hawaiian stories vulnerable to the white hand,” and among other directions, urges her not to write about the Night Marchers.12 Sure enough, Aiko is haunted by the Night Marchers and their unceasing drumming while at a writer’s panel in Austin, and even when she seems to escape them when the pages of her writing disappear, the ghosts she invoked do not vanish. Like Pili’s story, Aiko’s does not end with a clear resolution or the lesson learned we expected (“never write about the Night Marchers!”) Instead, back home on O’ahu, the drumbeats return—the story refuses to end, and the act of writing about this writer who writes about Hawaiian stories creates that presence which is a refusal of absence—a positive haunting, if that is at all possible. It attests to Haunani Kay Trask’s comment, roughly a quarter century before Kakimoto’s short story collection would be published, that Hawaiian literature as art can be “exposé and celebration at one and the same time; a furious, but nurturing aloha for Hawai’i.”13 Presence, even when haunted, and critique, even when complicated, situate these contemporary short stories as examples of Native Hawai’i writing back against the threat of disappearance.

The work that these short stories do in turning attention and giving voice to Native Hawaiian narrative strategies and spectral emergences does not exist in a vacuum—their storytelling power refuses the active attempts to silence Native voices that we can see in frightening scenes of the present. There are still other ghosts that roam the islands, and in terms of contemporary colonial visuals there are several that haunt Hawaiʻi and speak to the specter that refuses to be laid to rest, even if it is less immediately disastrous as nuclear testing.

I and others have been quite perturbed by the viral image of an overly-sunscreened Mark Zuckerberg hydrofoil surfing in Hawaiʻi in July 2020—a collection of memed comparisons includes ghastly figures from pop culture such as Voldemort, Michael Myers, and No-Face from Spirited Away, and show how easily this scene became a spectral presence. The kooky nature of the photo does not hide the background reason for some of our fright: its ghoulish undertones speak to the recurring emergences in the news cycle of Zuckerberg’s machinations in Hawaiʻi, most recently his in-process, $270 million Kauai compound complete with doom-proof bunker.

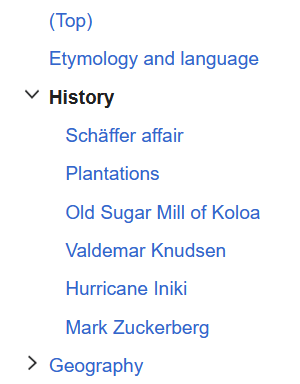

The haunting has a virtual presence as well; if you click to expand the history section on Kauai’s Wikipedia page, as seen above, you can witness the impact of this one figure, placed in parallel with other structures of violence (whether purposeful or acts of nature). As a real life, ghostly—yet still very present—figure intruding in the Native Pacific, Zuckerberg haunts a popular and accessible history of Kauai. Visually, whether it is through his circulating face in the photo above or his physically encroaching presence on the island made a different kind of permanent via online representation, Zuckerberg haunts Hawaiʻi—furthermore, the lifespan of his haunting is multifold: he is simultaneously presently around (and aground), while also haunting the future agency of Native Hawaiians with his financial moves. He can even be read as another spectrally adjacent force, that of the zombie, or the reanimated colonial presence: a version with the monikers of neoliberal and tech-bro, who yearns not for brains but for the aura of cool and the trappings of paradise that he hopes the hydrofoiling and his other island endeavors will bring. In any reading of his ghostly presence in Kauai, he represents the disruptive temporal jag that will close off a future of connectivity for some in order to create a closed-off, exclusive life that is once more the unburied arm of colonialism, reaching from the past into the future. There is no need to rehearse the reasons for continued colonial invasion onto (and into) the Hawaiian Islands: Kahakauwila reminds us of this in the very title of her collection, and as individuals and groups like Mark Zuckerberg continue to delve for their selfish paradise, they attempt to pave over Kānaka Maoli lives, livelihoods, and stories.

As the call for this cluster points out, sometimes we must come to terms with the experience of being haunted, a reminder of the way things can get lodged in our minds and the need to explore what it is that lingers so aggressively. Part of the experience of reading and teaching Kahakauwila and Kakimoto’s stories has been to register how the language, attitudes, Native characters, and worldviews they included have been left out of popular American media. While thinking about the immense presence and haunting aspects of their fiction, and considering the ways life on Hawai’i often appears in popular storytelling and news attention, one more experience needed to be worked out that helps frame the import of their fiction. It is a visual and a narrative scene this time, close to the very end of Mike White’s 2021 dark comedy television show The White Lotus, whose first season takes place at an exclusive resort in Maui. Like Kahakauwila’s titular story, a murder is at the heart of this show, and there are several avenues we could take to examine the haunted nature of the first season. But it is a less immediately eerie scene which places pressure on the purportedly critical framework of a series that depicts and ridicules white privilege.

In this scene, Quinn, the son of a white family vacationing in Maui, runs away as they depart the island and joins a group of brown, local paddlers he had been rowing with in earlier episodes. He literally paddles off into the sunset in the very last shot of the season, his storyline ending (as far as we can tell) in a triumphant rejection of his family’s instability and often toxic relationality in favor of a full embrace of the paddlers and the connection to nature they seem to represent. His narrative ending is decidedly quite haunting—his escape from his family is positively framed in music, lighting, and other cinematic choices, but it counters the show’s critique of settler colonialism and white appropriation of Native Hawaiian culture and sovereignty. At the end of all the torment that the show’s brown and black characters have suffered at the hands of the mostly white tourists who stay at the hotel, a young white person gets to have (or is, at least, framed as having) a successful return to nature, healthy activities, and community—he is the one who gets to claim ownership to those elements of Native Hawai’i, and who gets the choice to stay on or leave the island.14 Regardless of which he chose, it is the choice itself that haunts viewers who cannot help but see the closure of his story arc as an example of privilege, one which colors any warm feelings we may have towards his growth from awkward outsider to a more confident paddler. In this disconcerting way he fits somewhere, hauntingly, between Zuckerberg’s appropriation and between the more insidious “hope” for redemption via joining, rather than suing or building over, Native groups.

The paradise of Hawai’i that Kahakauwila and Kakimoto critically examine remains an object for white tourists’ self-empowerment and character growth: the show’s reluctance to give this storytelling convention up, to articulate the precise problematic of this and other scenes, is to create yet another specter of colonialism in visuals and narrative. The White Lotus does not release itself from a paradigm of erasure even as it depicts the talking points that would seem to usher in an acknowledgement of this haunted history of white action on Indigenous islands. This discomforting act of effacing Native voices in a narrative ostensibly about how damaging colonial intrusion has been in Hawai’i in some ways makes the resistant narratives of Native Hawaiian fiction and their own interpretation of haunting stories more necessary—their stories abound and circulate, and in doing so, create a presence that fights the attempted ghost-making of colonial incursions in Hawai‘i.

: :

Endnotes

- Brandy Nālani McDougall, Finding Meaning: Kaona and Contemporary Hawaiian Literature (Tucson, AZ: The University of Arizona Press, 2016) 33.

- Kahakauwila, “This Is Paradise,” in This Is Paradise (Hogarth, 2013), 10.

- Teresia K. Teaiwa, “bikinis and other s/pacific n/oceans,” The Contemporary Pacific 6, no. 1 (1994), 87-109.

- Jessica Hurley, “The Pikinni Ghost: Nuclear Hauntings and Spectral Decolonizations in the Pacific,” Apocalyptica 1 (2023), 85-106.

- I do not read or speak the Hawaiian language, and so I used the Ulukau Hawaiian Dictionary and the University of Hawai’i at Hilo’s Wehewehe Wikiwiki to translate this and other words.

- Megan Kamalei Kakimoto, “Every Drop is a Man’s Nightmare,” in Every Drop is a Man’s Nightmare (Bloomsbury Publishing, 2023), 16.

- Kristiana Kahakauwila, 10.

- Kahakauwila, 45.

- Stephanie Nohelani Teves, Defiant Indigeneity: The Politics of Hawaiian Performance (Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press, 2018) 155.

- Teves, 158.

- Kakimoto, 153.

- Kakimoto, 157.

- Haunani-Kay Trask, “Writing in captivity: Poetry in a Time of De‐colonization,” Wasafiri 12 (1997): 42-43.

- See Karim Townsend “On Mike White’s Primitivist Posthumanisms: Animality, Coloniality, and Racial Affect in The White Lotus” (2023) for further discussion of the show’s problematic portrayal of Quinn.