The opening page of Percival Everett’s landmark 2021 novel The Trees includes the following line: “the word between usually suggested something at either end, two somethings, or destinations.”1 This dictum recalls an idea at the heart of Everett’s earlier novel American Desert (2004). That novel’s narrator—whose identity is specified in the declaration “Ted chooses to relate his own story in third person”—speculates whether, after impossibly coming back from the dead at his own funeral, he is “Hyper-alive? Meta-alive? Sub- or super- alive?”2 These two moments are almost epiphanic when considering Everett’s oeuvre. Not only does he frequently revisit the idea of reanimating the dead or becoming undead—as Anthony Stewart says, “oftentimes, what we see in Everett’s work is a constant approach to something without ever actually reaching that object or ostensible destination. This asymptotic approach (in at least two senses of the word “approach”) gestures toward the infinitude that exists between categories.”3 Extending this, Stewart later unpacks the choice of name for American Desert’s protagonist, who actively occupies the space between the categories of alive and dead. As Stewart says, “[Ted] Street’s name characterizes the intermediate in itself, since the street can be a destination and also a route to a destination.”4

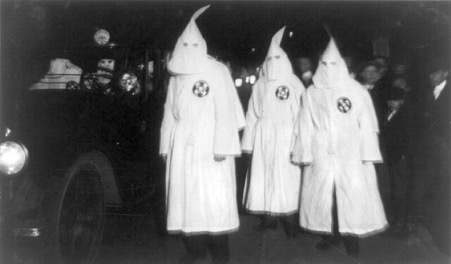

This precarious, intermediary, in-between position defines The Trees: a novel which revisits the traumatic 1955 lynching of 14-year-old Emmett Till in present day Money, Mississippi. Playing with time and realism, with what factually happened almost seventy years ago and what is not possible in the 2020s, in Everett’s novel, Till’s body seems to be re-appearing at crime scenes next to the additional, fresh bodies of White men connected to the 1955 murder. At various points in The Trees, it is even believed that Till is repeatedly coming back to life and dying, because the mysterious body keeps going missing in the time that elapses between new crime scenes, without a trace. Occupying an in-between zone or limbo, the experimental narrative of The Trees can be applied to Mark Fisher’s ideas, particularly what in 2012 he called the “disappearance of space,” which “goes alongside the disappearance of time.”5 Fisher elaborates, suggesting that “these are non-times as well as non-places.”6 We can read The Trees on these terms, because it conceives of the present tense as a complex and fractured non-time, while also depicting 21st century America as an impossible non-place, threatening to defy both the feasible and the tangible because of the desire to undo a deeply traumatic past. The novel’s time is a specific, named present that can only move forwards by reaching back to the past, which collapses tenses into one impossible moment. Its setting, meanwhile, has many similarities with the America Everett was writing and then publishing in, but resists realism. Therefore, non-time and non-place are conditional here. I will henceforth refer to this combined non-time and non-space as Everett’s novel’s in-between state, which connects to Fisher’s ideas while also departing from them. Fisher’s work also does not discuss the subject of race in detail, despite his fascination with temporality and trauma. Everett’s work has not been read alongside Fisher’s in this way, perhaps for this reason; but doing this makes what is implicit in Fisher’s work explicit, particularly his suggestion of time as politics of oppression and inequality.

In this context, to be in-between is to be uncomfortably in the middle of both different times and different existential planes. Expanding Jacques Derrida’s ideas on hauntology, Fisher discusses its “two directions”: “The first refers to that which is (in actuality is) no longer, but which is still effective as a virtuality . . . The second refers to that which (in actuality) has not yet happened, but which is already effective in the virtual.”7 These are some of the conditions of Fisher’s non-time and non-place paradoxes. Reading The Trees, we can connect Till’s tragically short life to this concept of “no longer,” despite the novel engaging with the (ultimately, unfulfilled) potential of bringing Till back to life and seeking justice; and we can assign the “not yet” but “already effective” to Everett’s projection of a bleak, apocalyptic future pre-determined by cross-generational racial inequality. In the novel, Till’s body becomes abstract and suggestive, less corporeal than symbolic, as if to represent American history’s diminishment of the substantial, physical, felt results of racialised mistreatment—relevant here as its extreme yet common endpoint: murder. As the character Jethro theorises at one point, “I think we’re all suffering from mass hysteria around here. You see, there weren’t no Black man at either crime scene. We’re just so afraid of Black people in this country that we see them everywhere.”8

As well as a literary symbol, Till’s body is an amalgamation of undead zombie, ghost, alien, and theistic possibility, and Everett’s large cast of characters describes it as each of these at different stages of The Trees. But the novel combines these potentials rather than pursuing just one, linking Fisher’s understanding of hauntology’s in-between state to his later discussion of “strange simultaneity.”9 In this 2014 book, Fisher suggests that “cultural time has folded back on itself, and the impression of linear development has given way to a strange simultaneity.”10 Till is the intersection of different, simultaneous narrative and genre potentials, allowing Everett’s novel to subvert the codes and conventions of historical, detective, and horror fiction. That is, The Trees is a historical novel caught out of time, in the present. It is a detective novel whose protagonists—the Mississippi Bureau of Investigation (the MBI)’s Ed Morgan and Jim Davis—struggle to crack the case, because historical fact might have been rewritten. It is also a horror novel that explains itself and addresses the source of fear out in the open, rather than leaving it an uncertainty or a mystery. Characteristics of the inconsummate and the insubstantial link these genre potentials, as do the themes of historical injustice and irresolution.

References to potential justifications for The Trees’ in-between state accumulate throughout the novel, functioning via hearsay: a tool which drives Everett’s dialogue-heavy work of over a hundred short chapters. Characters ranging from pivotal to peripheral contribute possible justifications, such as MBI director Lester Safer, who in a conversation with Ed and Jim, after the latter says “Dead people don’t walk,” reminds them “Except for Jesus.”11 Doctor Reverend Fondle gets on his knees and prays to “Jesus” about the disappearing Black body: a “sign” that he fears might be “the devil.”12 Later, Ed uses an alien invasion/conspiracy metaphor in a debate about negligence and inaction with Jim:

I know what pilots who see UFOs feel like now. If you tell everybody, they’re going to think you’re crazy. If you don’t say anything, well you’re not saying anything. Then the aliens invade, assume human form, start working in grocery stores, kill everybody you know, and take their places. You could be one.13

Another possibility is offered by the character Pick L. Dill, a coroner’s assistant. After the body seeming to be Till’s goes missing, Dill claims that “The son of a bitch is a fuckin’ ghost.”14

Similarly, the central character Mama Z, a 105-year-old who “calls herself a witch,” warns that “There are a lot of strange things happening . . . Supernatural things.”15 The farcical local sheriff, Red Jetty, says: “the peckerwoods is lookin’ everywhere but can’t find the walking dead Negro man.”16 The waitress at the diner Ed and Jim frequent, Gertrude, offers: “Somebody said there was a Black wizard or ghost running loose around town.”17 Other suggestions with the same preceding, capitalised adjective—one whose (mis)use is at the heart of Everett’s novel, and so many of his other works—include “Black Angel” and “Black ninja.”18 Pluralised suggestions are also given in the line “I’m seeing ghosts everywhere,” the reference to “disappearing Negroes,” and later descriptions of a “mob” of “perhaps thirty or forty strong” and “A mob of dead-eyed Black men [which] left behind six dead Whites.”19 This movement from single, impossible Black body to plural, collective mass identifies a shift from the possibility of one ghost to an undead horde. This shift comes as The Trees escalates from focused investigation into the mystery of Till’s body to a chaotic, all-out civil war, complete with a characterised Donald Trump as fumbling American president.

Even if it is revealed that the body in question does not belong to Till, Everett’s novel positions Black bodies directly within this in-between state recalling Fisher’s work on hauntology and simultaneity. In The Trees, a symbolic Black body is precariously balanced between alive and dead, which is an alarmingly realistic negotiation in 21st century America. Ever the iconoclast, responsible for a career of work that is deeply, unapologetically critical of American race relations, Everett again points to an extreme outcome of this negotiation: a “walk-in freezer” of “bagged people hanging from the ceiling.”20 The Trees casts these particular bodies in this scene as those of White men who are victim to a trend of copycat killings sweeping across America, even if non-White dead bodies also accumulate as the novel spirals into all-out war. Like The Trees’ starting, retaliatory murder of Till’s murderers, the subsequent copycat killings operate with a mirror logic, drawing attention to the long history of piled-up Black bodies that have triggered this subversive, measure-for-measure response, even if a Black body is no longer in the room. Not-Till’s body stops appearing next to White bodies as Everett’s novel goes on, because its careful, symbolic placement is so firmly tied up in the justification for the increasing White death toll that its physical presence at crime scenes has become redundant.

Such resignation is the tone The Trees often adopts. t is telling that Everett has the sheriff Wallace say: “The Black guy looks so dead . . . Well, these White men look pretty dead, but at least they look like they were once alive.”21 Wallace’s angle is different to the earlier claim, by Jetty, that Not-Till is “running around maybe killin’ people and getting’ hisself killed over and over again.”22 The body of who is later revealed as someone other than Till is blamed for the murders, but this body is also described as, impossibly, being cyclically murdered each time itself. This is the connective thread between Jetty’s suggestion and Wallace’s: whether returning to life and becoming undead (however many times) is causing additional White deaths or not, Not-Till is ultimately staying dead. Either as an effective zombie, ghost, or something else, Till’s body looks like it was never alive, as if the conditions of American racism were even “already effective” for an innocent fourteen-year-old child, to return to Fisher’s idea. These unfair conditions pre-determined Till’s tragic murder, which The Trees dramatises as repeatable, using the novel’s in-between state to defy realism and make its own rules.

In Fisher’s words, the traumatic past’s overspill into the present is due to “the failure of the future,” provoking hauntology’s “confrontation with a cultural impasse.”23 Returning to the “disappearance of time,” Fisher specifies how the future’s failure leads to its “disappearance,” which “meant the deterioration of a whole mode of social imagination: the capacity to conceive of a world radically different from the one in which we currently live.”24 The Trees converts this nuanced theoretical standpoint into something much simpler: blunt, justified pessimism, which cuts deeper than a tone of resignation. This feeling towards the future is informed by accumulated, multi-generational trauma. Fisher discusses “the acceptance of a situation in which culture would continue without really changing”; this concept manifests in Everett’s novel as a circular narrative structure of conflict.25 The Trees begins by reminding its reader of a historical murder without justice, and ends with a civil war built on a rapid escalation of unrest. Everett’s novel offers the sombre conclusion that war will only reset things—until other injustices present themselves, and are left equally unresolved. Till’s murder is just one history that could (and should) be addressed in the present. America’s shameful pasts are repeatedly unearthed, dusted down, and put under the microscope of contemporary literature. The trajectory of The Trees exposes this cycle, by moving further from its specific, idiosyncratic narrative situation the longer it goes on, then becoming a war that a number of triggers could lead real America to—from politics to legislation to weaponry. In another book on “capitalist realism,” influenced by 1960s German Pop Art and Michael Schudson’s book Advertising, the Uneasy Persuasion (1984), Fisher takes the deflated “acceptance” of unchangeable injustice even further, which I think can be applied to The Trees’ cyclical fate. As Fisher puts it, engaging in capitalist realism is conforming with “the widespread sense that not only is capitalism the only viable political and economic system . . . it is now impossible even to imagine a coherent alternative.”26

Later in this book, Fisher claims that “reflexive impotence” is attached to this disappearing imagination, this fading/failing future.27 As he says, reflexive impotence is where people “know things are bad, but more than that, they know they can’t do anything about it. But that ‘knowledge’, that reflexivity, is not a passive observation of an already existing state of affairs. It’s a self-fulfilling prophecy.”28 To this end, capitalism is an extreme case of collapsed temporal paradox. Fisher even writes that “Capital is an abstract parasite, an insatiable vampire and zombie-maker,” in a book that elsewhere analyses contemporary dystopian cinema, particularly Alfonso Cuarón’s Children of Men (2006).29 Fisher suggests that “the living flesh it [capital] converts into dead labor is ours, and the zombies it makes are us.”30 This resignation chimes with Everett’s in The Trees. His novel literalises both this metaphor of zombification and the idea of a static, paradoxical present tense. There may be inextricable connections to pivotal pasts and potential futures, but a cyclical and unchanging present pervades the novel’s vision of America. Appropriately, The Trees ends with hordes of either the undead or the soon dead marching towards one another on the streets, participating in a war that will change nothing: “Outside, in the distance, through the night air, the muffled cry came through, Rise. Rise.”31

This takes my discussion of The Trees back to the real history it has departed from by the time it reaches this ending. Its character Granny C is a parody of Carolyn Bryant, the woman who claimed (despite evidence indicating otherwise) that Till whistled at her and grabbed her hand at her store in 1955, which resulted in his lynching. Granny C can be read as an embodiment of The Trees’ in-between state—the insubstantial, fractured, simultaneous non-time and non-space I have discussed in this essay, which is also an unstable position of undead yet not alive. Granny C’s embodiment of this state is a case of productive, functioning literary symbol rather than a play on this, as Not-Till’s body frequently is. As a character, Granny C’s brief lifespan in Everett’s novel operates between past and potential, which is the evidence of in-betweenness The Trees most convincingly leaves us with. Early in The Trees, before the bodies start piling up, Granny C is described as “damn near dead, but . . . can hear just fine.”32 When her son Wheat is then murdered (after his cousin, Junior Junior, has been murdered), Granny C is said to be “unresponsive, but alive.”33 Before she herself dies, Granny C often zones out, and at one point “stared off into space,” prompting her family to worry if she is having a stroke and ask if she is okay.34 Junior Junior and Wheat’s murders provoke more focused zoning/spacing out, with Granny C thinking she is seeing shadows moving when she is home alone. She concludes that “I killed that boy, and now he done come back for all of us.”35 Granny C’s guilty conscience—and Everett’s narrative process of literalising this—escalates until she hallucinates Till in the room with her, at which point she dies, referred to later in the novel as her being “frightened to death.”36

Despite her vacant, empty, absent presence in rooms and scenes when alive, any potential for Granny C to become undead or spectral after dying (like Not-Till) is quickly disregarded: “We expect her to stay dead. It seems White people know enough to die and stay dead.”37 As this line from Red Jetty highlights, Granny C’s death is singular and permanent; it cannot be repeated nor made cyclical, so it is the opposite case to Till’s symbolic representation of generation after generation of murdered Black Americans. As the character Herberta Hind laments, “History is a motherfucker,” which simplifies an earlier conversation between Ed Morgan and Jim Davis on dinosaurs, extinction, and being stuck in the past.38 This conversation is echoed when Lester Safer observes how the town of Money is full of “pre-Civil War inbred peckerwoods” who are on their way to “extinction.”39 This is just one potential explanation for Money’s hermetic, archaic bubble—another is that it is effectively “still nineteen fifty.”40 Of course, this is the decade that Till’s lynching took place, but The Trees’ relationship with time is more complicated than being straightforwardly tethered to 1955. “This is the twenty-first century,” Jim reminds Ed, concerned for the backwards nature of Money, but also the wider America The Trees zooms out to in its second half.41 Everett’s novel is rooted to this specific moment in the past, but makes jokes about returning to much earlier, when there were dinosaurs. It also both alludes to present-day mundanities and zeroes in on specific real people who are relevant today, like recently re-elected Donald Trump. But most pressingly, The Trees forecasts a broken, failing future. By its final page, a civil war is underway and a global catastrophe is imminent. It is not difficult to interpret Everett’s more long-term projection: bodies will pile up and depleted new generations will replace old ones, filled with no more hope for a less dangerous, divided America.

: :

Endnotes

- Percival Everett, The Trees (Influx Press, 2022), 11.

- Percival Everett, American Desert (Faber and Faber, 2006), 3, 30.

- Anthony Stewart, Approximate Gestures: Infinite Spaces in the Fiction of Percival Everett (Louisiana State University Press, 2020), 6-7.

- Stewart, Approximate Gestures, 81.

- Mark Fisher, “What is Hauntology?,” Film Quarterly 66, no. 1 (2012): 19.

- Fisher, “What is Hauntology?,” 19.

- Fisher, “What is Hauntology?,” 19.

- Everett, The Trees, 61-62.

- Mark Fisher, Ghosts of My Life: Writings on Depression, Hauntology, and Lost Futures (John Hunt Publishing, 2014), 17.

- Fisher, Ghosts of My Life, 17.

- Everett, The Trees, 139.

- Everett, The Trees, 52.

- Everett, The Trees, 112.

- Everett, The Trees, 62.

- Everett, The Trees, 113, 168.

- Everett, The Trees, 33.

- Everett, The Trees, 78.

- Everett, The Trees, 86, 106.

- Everett, The Trees, 81, 83, 278, 321.

- Everett, The Trees, 322.

- Everett, The Trees, 251.

- Everett, The Trees, 83.

- Fisher, “What is Hauntology?”, both 16.

- Fisher, “What is Hauntology?”, 16.

- Fisher, “What is Hauntology?”, 16.

- Mark Fisher, Capitalist Realism: Is There No Alternative? (John Hunt Publishing, 2009), n. p. n.

- Fisher, Capitalist Realism.

- Fisher, Capitalist Realism.

- Fisher, Capitalist Realism.

- Fisher, Capitalist Realism.

- Everett, The Trees, 335.

- Everett, The Trees, 15.

- Everett, The Trees, 53.

- Everett, The Trees, 15.

- Everett, The Trees, 103.

- Everett, The Trees, 127.

- Everett, The Trees, 124.

- Everett, The Trees, 150.

- Everett, The Trees, 138.

- Everett, The Trees, 147.

- Everett, The Trees, 46.