If chatbots can act as simulations of lovers or therapists, or mimic the communicative presence of a dead loved one, then who is to say that they can’t also act as spiritual guides?

As practice-oriented, critical AI researchers, we want to go beyond the speculative fantasies attached to generative AI and instead focus on the tangible use cases that are already in place. How are ordinary people finding spiritual connections with chatbots, and what can help us make sense of these relationships? Through our ethnographic encounters with product managers and other workers at an AI spiritual wellness chatbot company, along with our engagements with chatbot users and our direct observations of their interactions with various chatbot personas, we have seen firsthand how algorithmic divination encounters are both produced and experienced. While we don’t ordinarily gain backend access to the algorithmic systems behind AI’s magic, we do have a sense of the social conditions that create the illusion.

Social conditions and technological developments, including the proliferation of powerful LLMs, created the right set of conditions for chatbot spiritual guides. During the early days of the COVID-19 pandemic, we witnessed an intensification of online interactions. As people grew more accustomed to remote learning and work environments and digitally mediated forms of communication and intimacy, the slippage between chatbot as tool, chatbot as spiritual guide, and chatbot as therapist is perhaps not so extraordinary. Chatbots have the capacity to act as divination tools, reflecting a user’s personality traits, anxieties, and desires right back at them. Their shape-shifting capabilities also lend them metaphysical properties. A chatbot’s persona is never just one singular, static entity, but changes according to the interactions and inputs of the user. In the same way that the magic of the social media algorithm or e-commerce recommendation engine is that it seemingly knows the user better than they know themselves, spiritual chatbots offer a simultaneously hyper-personalized and mysterious experience. The algorithm itself is already enacting a form of divination, so the instantiation of the psychic chatbot persona is just a more literal embodiment of this expected magic.

: :

User Applications of Algorithmic and GenAI Divination

The link between technology artifacts and occultism, or “technomancy,”1 is far from novel—for decades or even centuries, spiritual practitioners have turned to tools like Ouija boards, pendulums, dowsing rods, radio, and EVP recorders, claiming that these technologies assist with supernatural communication. More recently, digital device-based products have come to the forefront, offering the same benefits for users, many of which blur the boundaries between mental health, wellness, personal development, and spirituality. Now that we’ve entered the age of hyper-personalized content and generative AI, there’s been an explosion of chatbots for niche use cases, and spiritual development is no exception. Today, we see a flourishing array of AI chatbots designed specifically for spiritual inquiry, aiming to create digital avenues for personalized guidance and exploration.

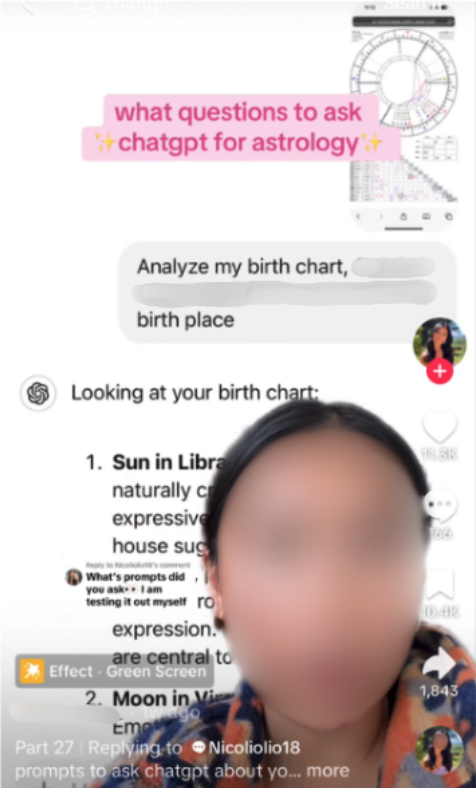

While language models like OpenAI’s ChatGPT are designed to generate coherent text based on statistical prediction, perhaps enacting a form of algorithmic divination from the outset, many users deliberately frame their prompts to elicit mystical or metaphysical responses and then treat the outputs as spiritual guidance or oracular insights. For example, some users feed GPT their astrological birth chart data and ask for personalized interpretations or advice based on planetary alignments. Others use it to generate affirmations, manifestation prompts, and ritual scripts, or even to channel messages from “spirit guides” or deities. Chatbots’ flexible language generation allows users to project intentionality onto the AI, mirroring how oracles, tarot cards, or pendulums have historically functioned as mirrors for inner inquiry.

Some platforms go further by branding the chatbot itself as a spiritual figure or guide. DeepakChopra.ai, for example, turns the controversial wellness icon into a chatbot persona that offers meditative advice, spiritual insights, and affirmations based on Chopra’s teachings. Here, the guru is no longer just a guide—he’s an interface, a branded hologram of presence.

Other products, such as You, Only Virtual, StoryFile, and Project December, provide AI chatbot simulations of the dead. Still other platforms present chatbots as companions, coaches, or friends that are intended to improve one’s relationship to wellness and productivity. This mode of engagement reflects a shift in how people relate to digital media—not as passive consumers of content, but as active co-creators of meaning by using algorithmic patterns as sites of mystical interpretation.

Part of what is striking about these chatbot companions as a service is their adaptability. Replika, one of the most popular chatbot companion companies, itself started out as a memorial and prototype, a tribute to the founder’s best friend built on social media communications. In its next iteration, launched in 2017, users were encouraged to train bots to become their data doubles. Now, the company offers different versions of its same experience, for those who need a mentor, or a girlfriend, or maybe just a pal. The anthropologist Fartein Nilsen describes how chatbot users train their Replikas to act more human, enacting a form of care for them. He also cautions against a knee-jerk judgement or disgust towards those who find companionship or soulfulness in their interactions with Replikas or other AIs, while pointing to the ways that users creatively adapt products to their own needs.

Chatbots present a unique interaction model in that they’re entirely open-ended. As a result, users are turning to them for various forms of knowledge, support, and guidance—from birth chart analysis to tarot card readings. But why do people gravitate to these tools for spiritual practices, especially when, at face value, non-human solutions might seem like the least likely to serve these needs? Besides the accessibility of being able to converse with the system 24-7, the chatbot can provide knowledge that is otherwise specialized. For example, users asking for birth chart readings would have had to either learn how to interpret their astrological charts or consult a practitioner. Some AI chatbot platforms even offer interactions with human psychic advisors that raise interesting questions about the implications of automating psychic labor and the role of occultism in the gig workforce, which we address in further detail below.

AI divination chatbots are an example of tools that support “technomysticism,” an approach within Neopaganism that views technology as a means to transcend physical limitations and achieve spiritual transformation. For example, the cyber-pagans of 1990s web rings. Such belief systems go beyond the practical use of technology as a tool and see a deeper, mystical connection between technology and the spiritual realm. Given the predictive nature of algorithms, it’s reasonable to see how lay users may mistake pre-programmed pattern recognition for divinatory guidance. Some scholars refer to this phenomenon as “algorithmic conspirituality”, a concept that reflects how algorithmically recommended content can feel like a revelatory, even cosmic, intervention—creating a sense of personalized spiritual insight mediated by technology: “In many ways, people trust algorithms to tell them things about themselves that they cannot see.”2 This interpretation stems not from mysticism, but from the algorithm’s ability to provide tailored advice by analyzing and inferring details from vast amounts of user data, which is not all that dissimilar from the people reading skills of professional occult workers like tarot readers or psychics.

: :

The Dangers of AI Divination

To some extent, these practices are a continuation of histories of mediated relationships with the spiritual world. But what is new is that corporate algorithms and hyperpersonalization, along with generative AI technology, are intensifying the relationship between media and spirituality. As critical AI scholars, we must delineate some of the potential harms users face through their interactions with chatbot spiritual guides, the material conditions under which such chatbots are produced, and their downstream consequences for occult practitioners. In many respects, the potential harms associated with spiritual guide chatbots are similar to the issues with other kinds of chatbots and personas, although the intersection of wellness and mysticism, along with the veneer of predictive capability or divination, may be especially dangerous in some cases.

Chatbots themselves are not static or permanent—at any point, they may drastically change, break down, or even disappear. A software update might alter the chatbot’s persona, or a company might go bankrupt and take the chatbot down with it. The fragility and finitude of chatbots derive from their dependence on corporate decision-making, ephemeral platforms and operating systems, and other infrastructures beyond the intimacy afforded by the interface. A user who comes to rely on a specific spiritual guide persona might be distraught when the company decides to tweak that persona through software updates or sunsets it altogether. For users who become emotionally dependent on the specific persona of a tarot reading chatbot, the loss of this relationship might lead to a sense of loss.

Spiritual chatbots provide a space simultaneously to understand the magical underpinnings of AI and to explore the impacts of AI on marginalized communities. As media philosopher Damien Patrick Williams argues, the magical qualities of technology are best understood through the perspectives of people who are most affected by AI systems: “Many still feel that values and religious beliefs are and should be separate from technoscientific inquiry. I argue, however, that by engaging in both the magico-religious valences and the lived experiential expertise of marginalized people, ‘AI’ and other technological systems can be better understood, and their harms anticipated and curtailed.”3 Chatbot assistants are being integrated into various care contexts to fill in for structural gaps and inequalities, often without any kind of impact assessment or, in some cases, even basic user testing. LLM-based chatbots are being used to provide support to marginalized groups who lack access to care or their own data.4 This kind of application carries a great deal of risk and potential harm to individuals and communities. For example, researchers found that LLM-based chatbots failed to grasp the nuanced issues experienced by members of the LGBTQIA+ community even after fine-tuning.

Some chatbot use cases point to the slippage between medicalized or official care and informal support that a non–professional might provide. Tech companies seem to have an obsession with creating an AI “friend” or a peer, and products like Replika are presented as an “AI friend” or companion. OpenAI’s Sam Altman has regularly rhapsodized on the promise of personalization, imagining that LLMs are essentially going to be able to cater to everyone’s individual needs in a real-life version of the film Her. As users ask for wellness advice in combination with divination practices, however, they can develop feelings of overdependency. Asking a chatbot if a relationship is doomed based on star signs or seeking advice on one’s life purpose through a birth chart reflects the platform or system’s growing role as an unregulated emotional support system. Without the nuance or accountability of human guidance, these interactions risk reinforcing biases, encouraging magical thinking in high-stakes decisions, or substituting relational support with an opaque, pattern-driven model.

Simulated conversations, be they from divination tools or companion AIs, also raise serious data privacy concerns, even if they market themselves as lighthearted or therapeutic. For example, sites like Texts From My Ex require users to upload deeply personal message histories—text with exes, no less—for the AI to then analyze and interpret. While the service might be tempting to some, even if a platform claims it doesn’t store the data, there’s an inherent risk in transmitting intimate conversations to a third-party system, especially one that operates as a black box. Perhaps more intuitively, there’s also the issue of consent. Your ex probably doesn’t agree to have their texts fed into an algorithm for analysis, and beyond that, it’s unclear how the data is trained, what it’s doing with the data in the moment, or how these insights might reinforce biased interpretations.

The conditions under which such chatbots are produced and fine-tuned also contribute to the potential dangers of spiritual AI companions. In our time with one spiritual wellness chatbot company’s product manager, we witnessed last-minute design changes, the product manager’s lack of decision-making powers, and rampant staff turnover. As the goals of the product kept shifting, and its relationship to both wellness and spirituality influx, it was difficult for us as researchers to fully assess what the potential harms might be. There are even cases of chatbots fueling spiritual psychoses in users, where they believe that ChatGPT is revealing to them the secrets of the universe and allowing them to become prophets.

The magic of AI, of course, is also built on the underpaid labor of data annotators who fine-tune models and the stolen creative labor of writers and other artists. The use of AI as a spiritual guide can also have downstream labor impacts on actual occult practitioners like psychics, astrologers, and tarot readers, including the workers who provide piecework on platforms such as Keen, a platform for on-demand psychic advisors, and Moonlight, a platform that allows Tarot readers and other practitioners to connect with clients and perform virtual readings. Spiritual guide chatbots threaten the livelihoods of occult gig workers while introducing new potential issues for users. Chatbot replacements for care workers are an excuse to replace workers while also putting users at risk. And this has happened in other contexts. For instance, the National Eating Disorder Association created a chatbot when its helpline workers attempted to unionize, and the chatbot, in turn, encouraged users in their disordered eating habits. What are the differences between parasocial relationships with human psychic advisors and their chatbot counterparts? And what are the potential dangers for both users and occult workers? When we evaluated a company’s spiritual chatbot personas with a diverse set of users, the very same company also happened to own a gig platform for psychic advisers, threatening the jobs of those occult platform workers.

In this sense, spiritual AI does not offer companionship or clarity—it offloads care into code and rebrands it as mysticism. Still, users find something meaningful here, and that something—be it through catharsis, connection, or curiosity—demands to be taken seriously. These interactions complicate the boundary between the sacred and the synthetic, or the spiritual and the scripted. We must ask ourselves, if people are turning to algorithms for revelation, what kinds of futures are we engineering into being?

: :

Endnotes

- Emma St. Lawrence, “The algorithm holy: TikTok, technomancy, and the rise of algorithmic divination.” Religions 15, no. 4 (2024): 435.

- Kelley Cotter, Julia R. DeCook, Shaheen Kanthawala, and Kali Foyle, “In FYP We Trust: The Divine Force of Algorithmic Conspirituality,” International Journal of Communication 16, no. 1 (2022): 1-23.

- Damien Patrick Williams, “Any Sufficiently Transparent Magic . . . ” American Religion 5, no. 1 (2023): 104-110.

- Jorge A. Rodriguez, Emily Alsentzer, and David W. Bates, “Leveraging Large Language Models to Foster Equity in Healthcare.” Journal of the American Medical Informatics Association 31, no. 9 (2024): 2147-2150.