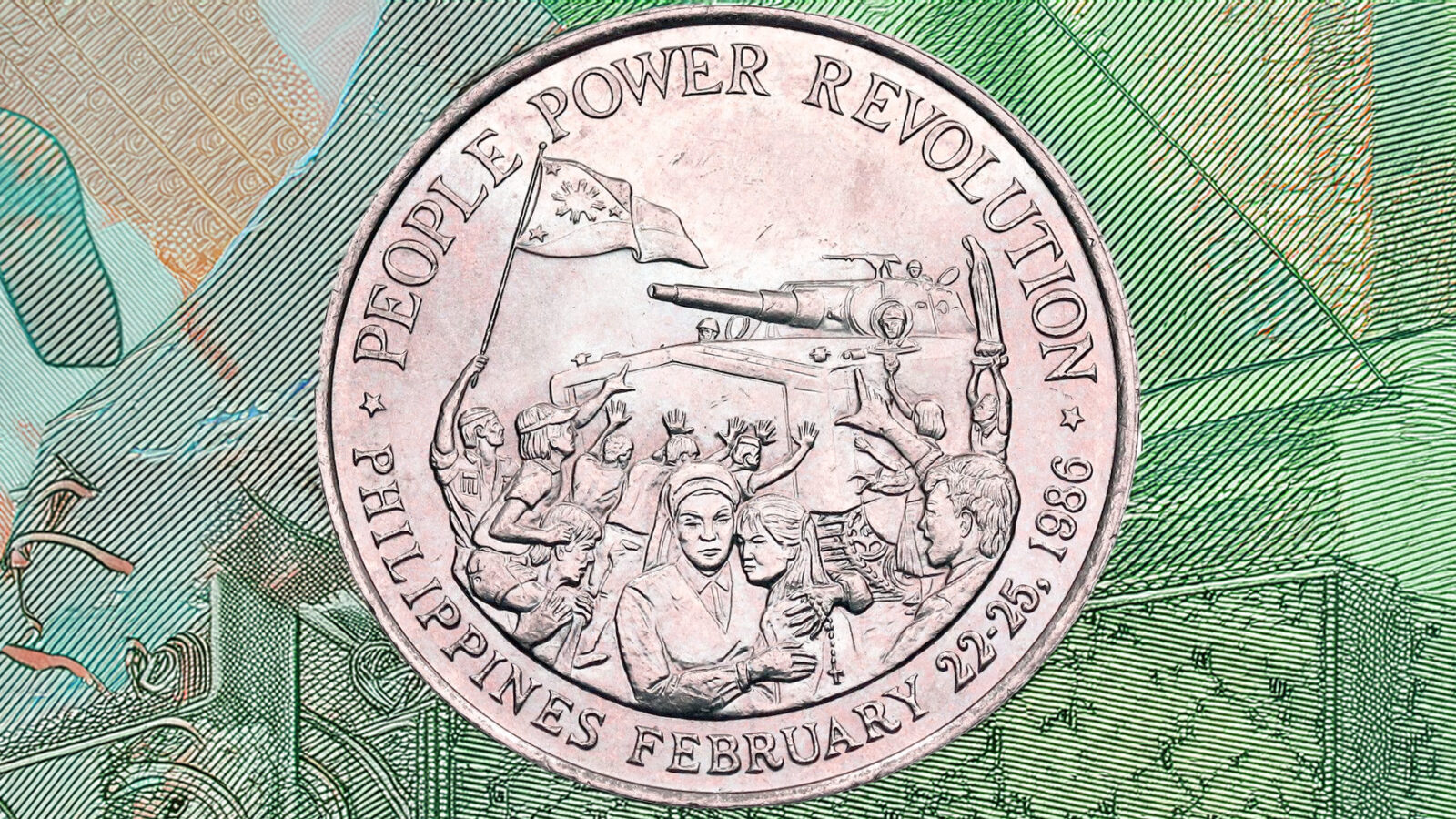

In February 1986, millions of Filipinos marched and protested along Metro Manila’s busiest thoroughfare, Epifanio de los Santos Avenue (EDSA). The momentous EDSA Revolution achieved the following: the ousting of Ferdinand Marcos after more than two decades of autocratic rule; the installation of the country’s first female president, Corazon Aquino; and the nominal restoration of democracy in the Philippines. While Aquino’s rise to power was replete with the hopeful fervor of a young nation emerging from twenty-one dark years of the Marcos regime, a critical reassessment of the period demonstrates that “the promise of political liberation and economic and social progress that accompanied the overthrow of the Marcos dictatorship in February 1986 had remained just that: a promise.”1 No longer linked to the possibility of an alternative political reality, that promise of socioeconomic progress now structures the pernicious capitalist realist belief that Philippine development can only be achieved via the departure of millions of overseas Filipino workers (OFWs) and their diligent return of economic remittances. Against this foreclosure of the social imaginary, a mode of diasporic Filipina writing has departed from the long tradition of Philippine realism and arrived at a critical irrealist aesthetic capable of imagining otherwise.

When Mark Fisher insisted that capitalist realism constrains our ability “to imagine a coherent alternative”2 to the relentless regime of value accumulation, the late theorist diagnosed a Global North riven by the neoliberal privatization of social welfare initiatives. While Fisher claimed the specter of “Nanny State” government intervention continued “to haunt capitalist realism”3 in post-Thatcher Britain through “its failure to act as a centralizing power,”4 the post-Marcos Philippine government, by contrast, consolidated its authority by imagining state-sponsored labor export as the inevitable paradigm for its developmentalist aspirations. The post-1986 Philippine government has been decried as an “anti-development state”5 whose failures to “deliver economic prosperity and reduce inequality”6 have resulted in a seemingly inexorable dependence on state-sponsored labor export—a world-historical development wherein “close to 10 percent of the Filipino population […] now work or live abroad and, according to recent surveys, one of five Filipinos wants to migrate.”7 The daily sacrifices made by millions of overseas Filipino workers (OFWs) reveal an altruistic hedonism of deferral—a Global South complement to Fisher’s depressive hedonia8 in the Global North—wherein the OFW’s suspension of their individual pleasure principle enables the very livelihoods of their kin left behind in the Philippines. The anti-development state has disavowed any obligation to its citizens and, in the bleakest neoliberal fashion, offloaded its responsibility for social reproduction onto individual Filipinos that now, in a cruel twist of irony, disproportionately perform much of the Global North’s own outsourced socially reproductive labor.

A national-diasporic iteration of global capitalist realism, the “there-is-no-alternative” propagation of state-sponsored labor migration as the only recourse for improved domestic livelihoods has paradoxically inserted Filipino subjects into the spaces and scenes of deteriorating domestic life in the Global North where many OFWs now work abroad while on precarious, temporary contracts. In the same post-Fordist economies diagnosed so acutely by Fisher, such as those of Britain and the United States, wherein the internal contradictions of capital’s innate tendency toward falling rates of profit appear as stagnation and not terminal crisis, one can find hundreds of thousands of OFWs, the majority being Filipina women, laboring away in the margins of everyday life—the often overlooked spaces of social reproduction. Reproductive labor can be unwaged, such as most domestic work performed within immediate familial contexts, or waged, which is the case for the sizable population of Philippine caregivers working abroad. Yet, as Nancy Fraser points out, “capitalist societies separate social reproduction from economic production, associating the first with women and obscuring its importance and value. Paradoxically, however, they make their official economies dependent on the very same processes of social reproduction whose value they disavow.”9 This simultaneous occlusion and dependence reveals how, according to Fisher, “neoliberalism has sought to eliminate the very category of value in the ethical sense,”10 and nowhere is this disavowal more evident than within the neoliberal family form of the Global North.

Examining the foreclosing effects of capitalist realism on the intimate registers of the atomized Northern family, Fisher locates a domestic site wherein a parent’s depressive hedonia, or following the pleasure principle to their own detriment, results in the abdication of responsibility for the socialization of their children. As one generation of depressive hedonists refuses to stand in the way of their children’s self-defeating pursuit of individualized pleasure, the less-than-virtuous cycle continues. As depressive hedonia’s perpetual longing after pleasure is mediated through consumerism, so, too, have atomized families in particular class strata throughout the developed world increasingly turned to the consumption of commodified care from the Global South to “sort out problems of socialization that the family can no longer resolve.”11 And as overseas Filipino workers step into the domestic spaces of the neoliberal family form in the Global North, their altruistic hedonism of deferral, the suspension of the pursuit of their own pleasure for the benefit of kin left behind in the Philippines—is therefore paradoxically tasked with maintaining the Global North’s consumption-driven depressive hedonia.

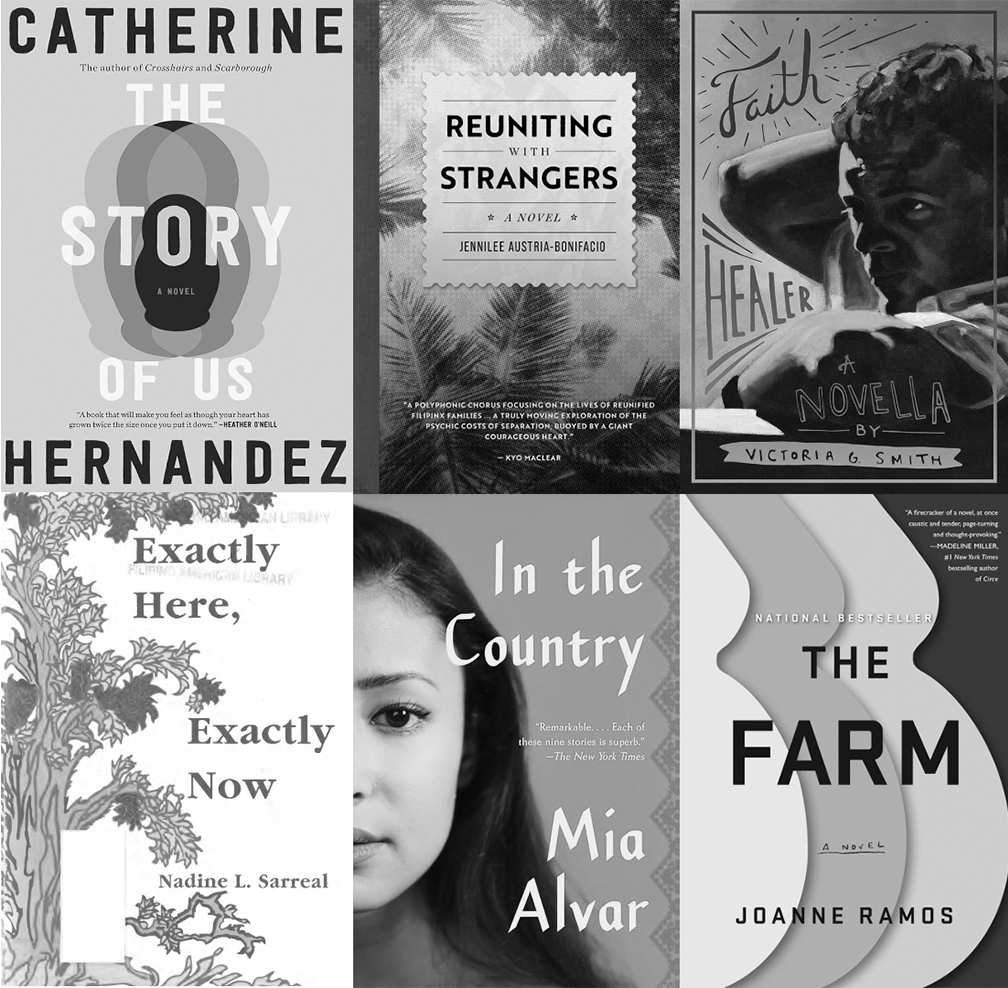

Fictional narrative writing from the massive Philippine diaspora has begun to aesthetically register the bleak, contemporary Filipino reality caught between the labor-sending push of the anti-development state and the labor-receiving pull of consumption-driven depressive hedonia. Understanding these two poles as intimately linked, recent diasporic Filipina literature has deployed a unique mode of critical irrealism whose formal experimentation and narratological disruptions produce an anti-development aesthetics aligned against the combined but uneven experience of capitalist realism in the labor-sending Global South and labor-receiving Global North. First described by the Marxist theorist Michael Löwy, critical irrealism refers to the aesthetic critique of the “disenchanted reality of modern, meaning capitalist, society,”12 or what Mark Fisher described in another way as the “pervasive atmosphere”13 of capitalist realism. By writing narratives about reproductive-laboring OFWs that are unburdened from the pretense of mimetic verisimilitude, contemporary diasporic authors such as Nadine Sarreal, Victoria G. Smith, Joanne Ramos, Catherine Hernandez, Jennilee Austria-Bonifacio, and Mia Alvar are powerfully capturing the transnational contradictions of capitalist realism. These authors’ irrealist, anti-developmental aesthetics index the Philippine consequences that attend a global market for waged reproductive workers: a state that pushes these workers out and a depressive hedonia that consumes their commodified labor in its own pursuit of pleasure.

I call this specific mode of critical irrealism from the Philippine diaspora reproductive irrealism, as it finds its literary-formal abstractions conditioned by the unreal reconfigurations of everyday life attendant to the socio-economic abstractions wrought by the Philippines’ dependence on its feminized OFW diaspora. The anti-developmental aesthetics of reproductive irrealism tend toward surreal or metafictional abstraction because the new social forms tethering overseas reproductive labor to the Philippines are themselves deeper abstractions of already abstracted social relations. The transnational care chains linking Filipina reproductive labors plainly reveal how waged abstract labor abroad depends on unwaged concrete labor at home. The transnational remittances that suture OFWs to the Philippine domestic economy plainly reveal how the money form, an abstract measure of value, concurrently functions as the medium of circulation. And, most notably, the concrete temporalities of social reproduction plainly reveal a more primary level of abstraction undergirding value-producing socially necessary labor time. That these strange social forms—care chains, remittances, and socially reproductive temporalities—are, by and large, feminized thus reveals how overseas Filipina writing is uniquely situated to register these shifts.

Nadine Sarreal interrupts her short story “Case 2183-93, Angela Cabading, Age 26” (2000) with a mediatic bricolage of various societal perspectives on Filipina domestic workers.14 In Faith Healer (2016), Victoria G. Smith conditions the suspension of readerly disbelief in a novella linking diasporic exile to the literal loss of miraculous healing powers.15 Joanne Ramos follows an overseas Filipina through the speculative dystopia of a surrogacy mill in the Hudson Valley in her novel The Farm (2019).16 Catherine Hernandez tells the story of a live-in nanny in Toronto from the perspective of a newborn infant in The Story of Us (2023).17 And Jennilee Austria-Bonifacio writes an entire chapter of her novel Reuniting with Strangers (2023) in the form of a “Caregiver’s Instruction Manual” for newly arrived migrants to Canada.18 While the specificities of these critical irrealist interventions, whether at the level of form or content, each provide unique insights into the contradictions subtending the experiences of OFWs, they all stem from a shared sense of the surreal demands placed on reproductive labor from the Philippines.

As a salient example of these interventions, Mia Alvar’s short story “Esmeralda” (2015) from the collection In the Country deploys a reproductive irrealism that denaturalizes the Philippine export of and American dependency on migrant Filipina reproductive labor by formally shifting normative modes of narration.19 Alvar’s story tracks its eponymous protagonist, an undocumented Filipina cleaning woman who works evenings in the World Trade Center, as she travels from her outer-borough apartment to Ground Zero on the fateful morning of September 11th, 2001. Interspersed throughout this narrative present are flashbacks in which Alvar recounts the development of an office relationship between Esmeralda and an American analyst working late nights in the Twin Towers. While the narrative elements of the story’s emplotment are straightforward enough, Alvar’s reproductive irrealism, which is explicitly linked to the precarity of Esmeralda’s socially reproductive labor, subverts any easy narrative accounting by deploying an anti-developmental aesthetic that hinges on the disorienting use of the second-person narrative perspective.

Across nightly interactions with the American analyst, Alvar’s “you” simultaneously hails Alvar’s hailed reader and Alvar’s protagonist, and it inhabits a complicated migration history from the Philippines to New York City. Alvar’s “you” learns about the first move from the provinces to Manila to work as a domestic helper for a cousin in the capital region. “You” ascertain how that cousin then “moved to Qatar and bequeathed you, like a car or a perfectly good table”20 to another employer that subsequently moved to New York, only to terminate “your” contract once there. “You” establish that “you” eventually overstayed “your” visa and lived as an undocumented domestic worker for over a decade. “You” learn that to support “your” family in the Philippines with monetary remittances, “you” accepted only cleaning jobs that paid “cash in envelopes, from people who never asked to see your papers as long as you had references and kept their sinks and toilets spotless.”21 Formally disrupting the normative capitalist realist development consigning migrant Filipina reproductive labor to invisible margins within the American social imaginary, Alvar’s jarring second-person “you” narration structurally implicates its hailed reader in the precarity attached to Esmeralda’s experience overseas. Alvar’s reproductive irrealism thus powerfully reimagines readerly empathy as political-economic culpability, thereby holding the Global North and South’s combined but uneven manifestations of capitalist realism to account for their mutual complicity in the continued subordination of overseas Filipina reproductive labor.

Contemporary diasporic Filipina fiction is advancing an anti-developmental aesthetic that denaturalizes the transnational exploitation of Filipina OFWs by disarticulating their reproductive labors from the Philippines’ capitalist realist belief in the inevitability of state-sponsored labor export, as well as the Global North’s capitalist realist dependence on commodified care. These reproductive irrealist literary texts thus reveal how, as Fisher puts it, “capitalism’s ostensible ‘realism’ turns out to be nothing of the sort.”22 While capitalist realism forecloses imaginable alternatives to our current conjuncture, reproductive irrealism reimagines the ways in which the capitalist world-system continues to depend on reproductive labor from the Philippines. And in that reimagined recognition lies the promised threat of another reality liberated from labor export and commodified care.

: :

Endnotes

- Walden Bello et al., The Anti-Development State: The Political Economy of Permanent Crisis in the Philippines (Anvil Publishing, 2009), 1.

- Mark Fisher, Capitalist Realism: Is There No Alternative? (Zero Books, 2014), 2.

- Fisher, 62.

- Fisher, 62.

- Bello, 3.

- Bello, 3.

- Bello, 3.

- Fisher describes depressive hedonia as the “inability to do anything else except pursue pleasure” (Capitalist Realism, 22).

- Nancy Fraser, “Crisis of Care? On the Social-Reproductive Contradictions of Contemporary Capitalism,” in Social Reproduction Theory: Remapping Class, Recentering Oppression, ed. Tithi Bhattacharya ( Pluto Press, 2017), 24.

- Fisher, 16-17.

- Fisher, 71.

- Michael Löwy, “The Current of Critical Irrealism: ‘A moonlit enchanted night,’” in Adventures in Realism, ed. Matthew Beaumont (Blackwell Publishing, 2007), 196.

- Fisher, 16.

- Nadine Sarreal, Exactly Here, Exactly Now (Giraffe Books, 2000).

- Victoria G. Smith, Faith Healer ( Brain Mill Press, 2016).

- Joanne Ramos, The Farm (Random House, 2019).

- Catherine Hernandez, The Story of Us (Harper Avenue, 2023).

- Jennilee Austria-Bonifacio, Reuniting with Strangers (Douglas and McIntyre, 2023).

- Mia Alvar, In the Country (Vintage, 2015).

- Alvar, 163.

- Alvar, 157-158.

- Fisher, 16.