In collaboration with the artist Emmanuel Nwogbo II, this digital exhibition deploys works of montage that pair seemingly disparate images in order to complicate and extend the legacy of the Biafran struggle for independence at the heart of the Nigerian Civil War (1967–70). We aim both to unravel the historical complexities of collaborations between Biafran leaders and Western agents and to foreground, today, the market relations between the secessionist leaders and Western publicists who contribute to a crisis of mass starvation and suffering. In doing so, we adopt an aesthetic of Africanfurutity that showcases what Sakiru Adebayo terms Africa’s “continuous past” to define the continuity of crises in postcolonial Africa.1 Deployed here to signify the postwar haunting resonance of the Biafran crisis, Africanfuturity offers novel possibilities in discussing the arc of Biafran history.

Striving for independence, Biafra emerged in the Eastern region of Nigeria in response to the 1966 pogroms against the Igbos that led to their mass exodus from the North and into the Eastern region. Nigeria was backed by imperial powers—the Soviet Union and the United Kingdom—who provided military support and equipment. To the chagrin of these major key players, Biafrans were able to sustain the war, mobilizing the power of visual media through their Geneva-based intermediary, the Public Relations firm Markpress. Nonetheless, the secessionists were forced to capitulate in 1970 due to Nigeria’s imposed blockade, which led to the mass starvation of people under Biafran authority. The images of hunger and suffering that proliferated in Western media ignited public discourse and galvanized humanitarian aid. It is this circuit of Western cultural production that situates Biafra as one of the most critical sites in the history of the humanitarian industrial complex.

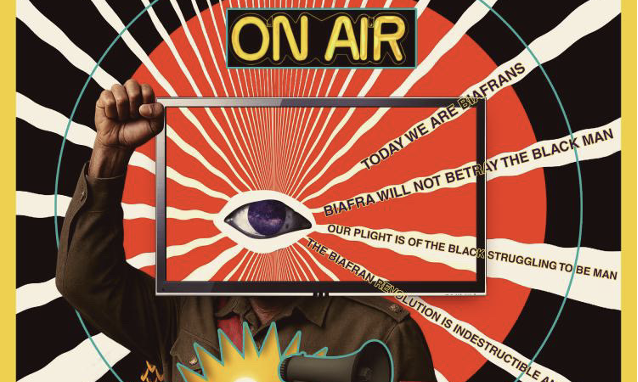

Attending to the relations between Biafran leaders and the Western journalists and publicists, our images foreground the instrumentalization of crises by transnational elite-classed subjects, as collaborators within the circuit of humanitarian cultural production. Biafran leaders adopted two main propaganda approaches: one targeted inward at Biafran subjects and the other directed outward to the international community. Our first montage represents the former strategy through a proto-nationalist subject in a Biafran uniform, a fist raised in the air. Before this subject is the Biafran sun with an accompanying speaker. And where the subject’s face should be, we find an outline of a TV screen with an eye in the middle. In the background of the image is an orange circle with white rays streaming outwards from the eye. Along the rays are embedded quotes detailing the Biafran struggle: “Today we are Biafrans,” “Biafra will not betray the black man,” “Our plight is of the black struggling to be man,” and “The Biafran revolution is indestructible and eternal.” These quotes are pulled directly from the Ahiara Declaration (1970), a speech delivered by the Biafran leader, Colonel Odumegwu Ojukwu, at the tail end of the war. Drafted by the Biafran intelligentsia, comprised of Igbo artists and scholars, the text is ideologically heavy-handed and is often seen as a propaganda tool. The work points to the Biafran narrative of Black African self-determination that the Biafran leadership rhetorically employed throughout the war, while also reimagining Biafran propaganda through a speculative aesthetic.

Africanfuturism forms the aesthetic basis of the Biafran self-conception as a fully developed, modernized nation—the revolutionary vanguard for Black liberation. As Douglas Anthony argues, modernity inflected Biafran national identity “as the vanguard of a progressive post-colonial Africa.”2 Our artwork foregrounds the propaganda machine by incorporating text directly from the Ahiara Declaration, which was a key strategy to bolster Biafran morale in the face of its impending capitulation. This artwork plays on the strategic uses of media and culture to reinforce political ideology. Deploying Africanfuturity to underscore Biafran modernity, we emphasize colour and lighting: the white rays and the central eye create an almost omniscient sense of Biafran authority—its sovereignty—reinforcing the secessionist nation’s purported indestructibility and eternal strength. This image becomes a visual symbol of what I call the Biafran gambit: the leadership’s strategic use of all forms of cultural texts to sustain the belief of its sovereignty, despite the project’s tragic collapse.

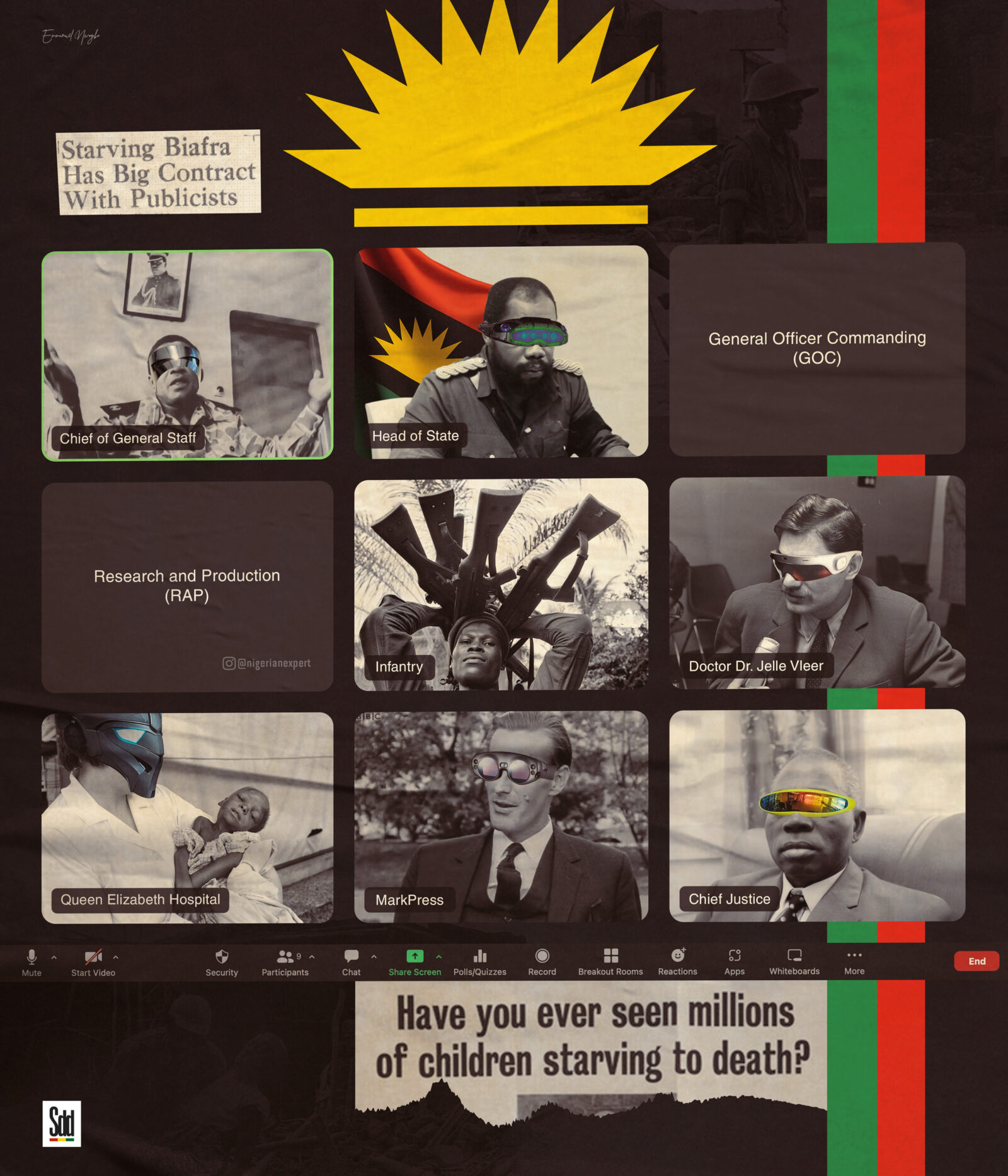

Our second montage highlights the collaboration between key leaders through the depiction of a virtual meeting. This conceptual meeting features a representative of Markpress, members of the Biafran leadership (including Chief of General Staff Major General Phillip Effiong, head of state General Chukwuemeka Odumegwu Ojukwu, General Officer Commanding Alexander Madiebo, and Chief Justice Sir Louis Mbanefo), the Biafran arms manufacturing Research and Production institute, Dutch medical doctor Dr. Jelle Vleer (of Terre Des Hommes), and a nurse holding a Biafran child at the Queen Elizabeth Hospital. The Biafran flag, with its prominent half of a yellow sun and green and red stripes, along with two headlines that read “Starving Biafra has big contracts with Publicist” and “Have you ever seen millions of children starving to death?,” serve as a backdrop for this virtual meeting. The singular representation of the Biafran mass can only be located in the sickly child: she is the starving Biafran, and unsurprisingly, she is incapacitated and rendered mute. With the exception of the infantry, all the meeting attendees don eyewear that signals their integration within this modernized, hyperbureaucratic engagement. The nurse’s face shield acts as a protective barrier that signals a pernicious racial coding, distancing whites from Blacks. Here, the nurse-child photograph serves as a key representation of the humanitarian visuals that emerged during this conflict, one that signals whiteness as the embodiment of health and vitality, distanced from the Black other and the heart of darkness from which this crisis unfolds, and positioned as the unsung heroes of the Biafrans.

Media coverage of the war foregrounded images of Biafran women and children, often unclothed to reinforce poverty and sickness, sustaining the myth of African corporeality. These images played upon colonial-era tropes of Black Africa as the dark continent. Thus, nationalist and exceptionalist Biafran rhetoric present in the Ahiara Declaration suggest an inherent tension between the dual propaganda approaches. The leadership’s ideological narrative of Biafra as an emerging Black power directly contradicts their use of images of suffering to sustain the war, which speaks more broadly to the significance of visuals that reaffirm racial stereotypes, particularly as they serve to underscore white Western exceptionalism. In addition, the Biafran leadership’s mobilization of humanitarian imagery as propaganda signals their desperation, even as they wield material agency that is contingent upon participation within a cultural marketplace. This highlights the imperial logic that buttresses the humanitarian industrial complex.

Focusing on the collaboration between Biafra and Markpress, our third montage envisions the commodification of suffering with posters and magazine covers of emaciated Biafrans, most of whom are women and children, and white subjects positioned as consumers. The prominent colors of blue and gray distinguish the consumers from the photographic objects of consumption. One sick Biafran child defies this clear binary. Positioned on top of a table, the child, folded in on her/himself, evokes a racist style of objectification that is rooted in the history of racialized experiments. Despite the clear racial coding of this visual that speaks to Western consumption and the objectification of Africans, the artwork also implicates Black subjects in market activity. Two Biafrans participate in the rhythm of commercial exchanges, with a man suggestively selling, and a woman ostensibly appreciating, these photographic representations.

Once again, the visual representations of suffering dovetail with a cultural marketplace through an Africanfuturistic aesthetic that signals Biafran modernity as participation under capitalism. Modern high-rises serve as a backdrop, while the blues impose an effect of movement that emphasizes fluidity and speed—effectively reinscribing the logic of Western progress. Herein lies the Biafran paradox: the leadership was consigned to reanimating colonial-era stereotypes for the preservation of the state, all the while ascribing to the belief in Biafran exceptionalism and sovereignty.

Returning to the heart of the devastation, the fourth artwork apprehends the culmination of the war. A small Biafran child clutches a radio on her shoulder, with a Biafran flag projected on the radio’s antenna. The iconic yellow sun dimly glows against the rest of the flag. Once intended to bolster morale, the flag, now hoisted within a land of graves, has lost its utility. The little girl stands amidst this grave as the only human subject. Dust rises in the background. The hardened earth signals desertification to epitomize war’s material effects. The colours yet again symbolize Biafran suffering, with the sole embodiment of life, the child, in greyscale: an apparition, perhaps. The prominent hues—red earth and green sky—reflect the colours of the flag but also the aftermath of air raids. Though hope is lost, the Biafran propaganda machinery endures. Thus, the artwork conveys the persistence of Biafran propaganda, along with its reliance on the visual as an instrument of war.

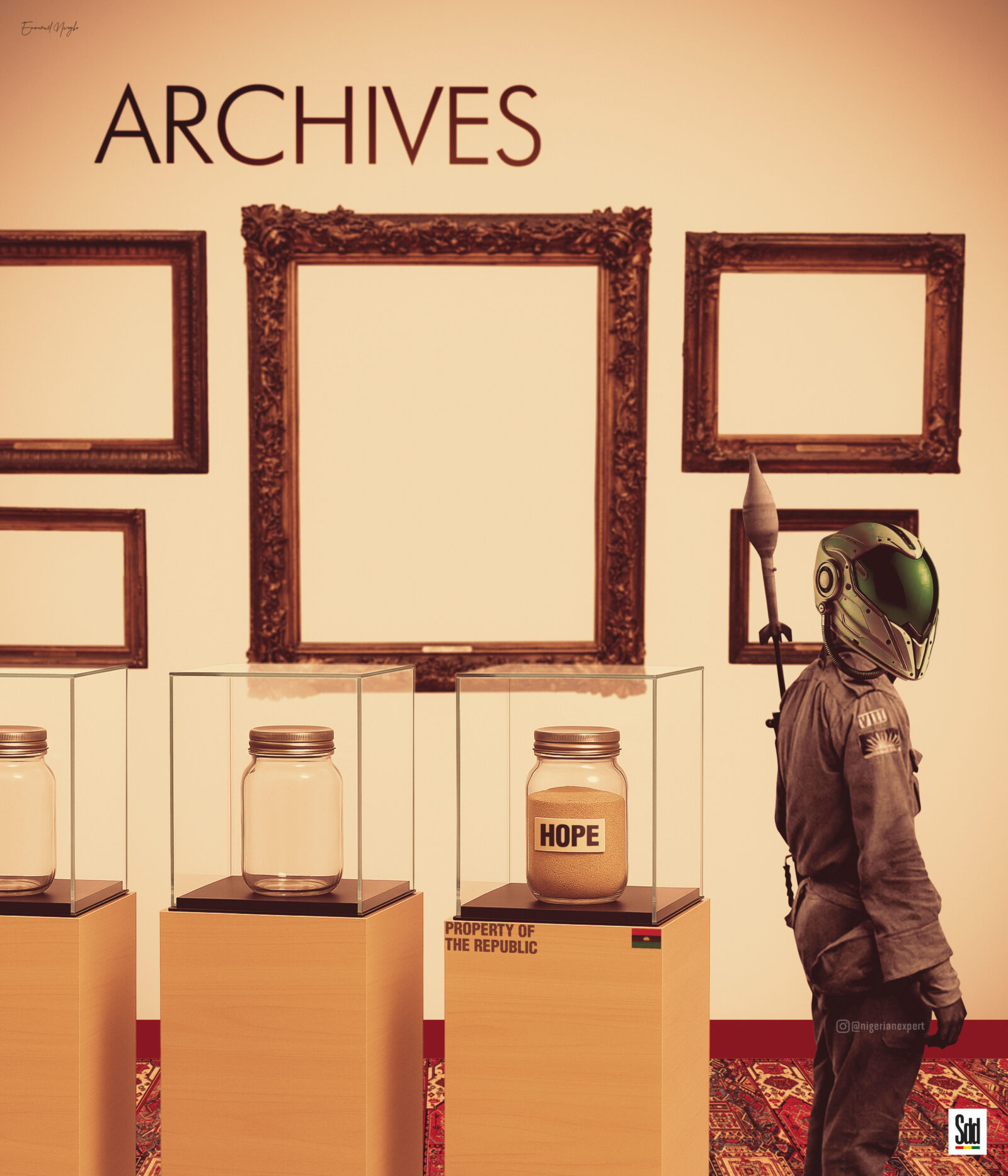

Our final artwork offers a postscript of the war. In it, a subject in a Biafran military uniform dons a galactic-inspired futuristic helmet and wields a rocket-propelled launcher, ceremoniously, like a staff. Evoking postapocalyptic regalia, the artwork registers a pessimistic conclusion to the Biafran story. It is spectral. The subject stands amidst a gallery of empty frames and jars, with the exception of a sand-filled jar that is labelled “Hope.” This jar rests on a stand with the inscription “Property of Biafra,” registering hope as a contaminant to be cordoned off, but also admired by an infinitely objectifying gaze. Once an aspiration, the Biafran nation becomes archived, contained within a gallery for one’s viewing pleasure. Despite the Biafran self-conception and its strategic pantomimic redeployment of colonial-era stereotypes, the war’s decisive implication—made evident by the secessionists’ failure to sustain independence—ultimately exposes the enduring power asymmetries between the West and Africa that shape the visual economy of suffering. The nation once reliant on its own objectification is indefinitely cast into this role: a self-devouring ouroboros. And, as viewers and audiences captivated by the siren call of spectral images, we are left to reflect on our own complicity.

: :