Lorna Simpson: Source Notes, survey exhibition

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

May 19, 2025 — November 2, 2025

: :

Inside the Helen and Milton A. Kimmelman Gallery (a tucked-away space in The Met’s Modern and Contemporary Art galleries) is a survey of Lorna Simpson’s large-scale paintings: glamorous portraits of bold and audacious women, archival materials that experiment with temporality and representation, and collages that remix Black feminine embodiment into ways of being and feeling beyond the human form. I floated through the open and welcoming gallery space as if I were seeing colossal statues, witnessing nature’s power, watching roaming celestial objects, even being with gods. Many of the paintings are over nine feet tall and eight feet wide, and they oscillate between opaque and transparent colors and textures. I was immersed in blues—sapphire, cobalt, aquamarine—and grays—graphite, charcoal, silver. I experienced the blurring of time. I was transported to eerie, icy landscapes that allude to Matthew Henson’s uncredited polar journey.1 I was reminded of decades that honored Black women’s beauty, writing, and culture as seen in pop-culture magazines, most notably Jet and Ebony, from the 1950s to the 1970s.2 I witnessed Simpson’s engagement with memory as it is felt and sensed in individual, distinct ways. Lorna Simpson: Source Notes invited me into a world that felt real yet elusive, familiar yet new—haunting.

During the late twentieth century, Simpson became known for her conceptual photography that challenges bodily representations of Black women in portraiture.3 Simpson’s use of archival photographs and materials is one expression of the haunting that I intuit in her work.4 Third Person (2023) builds on the headshot of a woman looking softly and solemnly into the camera, her hairstyle and makeup reminiscent of Black feminine styles of the 1960s. A portion of her face is washed in hot pink ink; the bright yet translucent pink is surrounded by opaque cobalt and phthalo blues, which hide more of her face than the pink. Analyzing Simpson’s use of watercolor, writer Elizabeth Alexander notes how the aquarelle is perfect for Simpson’s mission of calling attention to what “we cannot know in these women.”5 Simpson demonstrates how slippery memory and historical information can be. Opacity shows up in her archival methods as a refusal of the firm and concrete. Curator Adrienne Edwards discusses how memory is both clear and elusive in Simpson work, suggesting that the archival visuals are meant to be a “regathering” and “sensual, material commemoration” yet, at the same time, Simpson has a “long-standing tendency toward occlusion, opacity, and elusivity.”6 This sort of aesthetic dissonance further emphasizes the mode of haunting in Simpson’s work.

Shifting from conceptual photography, Simpson is now widely recognized for her practices of collaging and painting mid-to-late-twentieth-century Black models in galactic, godly, animalistic, and eerie settings. Ghosts and haunting also call attention to the ways Simpson’s visuals—the subject matter, colorways, brushwork, and collage techniques—provoke curiosity, seducing viewers to investigate what isn’t clear.7 Across her works, Simpson conjures Black communal desires to experience otherworldly, not-quite-here, and more-than-human embodiments. Simpson leans into surreal visuality, fragmentation, hybridity, and abstraction to offer representation of Black women that, as bell hooks suggests, give “poetic expression to the ethereal, and prophetic dimensions of visionary souls shrouded in flesh.”8 In many of the paintings in this exhibition, clandestine source images and documents are noticeable only upon careful scanning of the large paintings, and even then there are fragments that aren’t fully visible. Simpson makes viewers work for information, yet even diligent searching doesn’t disclose everything.

For Beryl Wright (2021) is a diptych of an ocean landscape with gradient blue streaks that give the painting texture. One side of the painting is a dark blue image of a foggy glacier, while the other side is a lighter image of an ocean-scape with opaque brush strokes appearing like heavy rain. The texture blurs the scene, replicating frigid Arctic conditions. Upon closer inspection, some of those streaks are not brushstrokes but are strips of writing taken from Simpson’s findings in publications in the mid-to-late twentieth century. The pieces of writing appear through cracks of blue, leaving most of the story hidden. The sliver of writing instills curiosity and invites the viewer to co-imagine the fuller story. Simpson’s themes of speculation are seen through the withholding of the entirety of the sources, forcing viewers to desire something more and to imagine what more could be—like a fiction.9 In this way, she cultivates an art practice that honors Black life as communal, historical, and not fully for public consumption.

Ghosts, as metaphors and as theory, have a significant place in Black feminist thought. Feminist literary scholars Marjorie Pryse and Hortense Spillers have written about conjuring as a storytelling practice that grants access to spiritual, metaphysical worlds.10 They argue that writers, and I would include visual artists, serve as mediums for past or elusive figures who are summoned in the creative works. Simpson’s methodology sees memory and its resurfacing as a felt and embodied phenomenon that gets triggered by certain sites, images, and events that can tell us more about Black life, if we pay close attention.11

Edwards sees something ghostly in Simpson’s work with meteorites, such as in did time elapse (2024), which depicts a singular large, long rock with distinct ridges and craters staged at the center of the painting, while the background is a streaky blur of grey and white. Edwards reflects on how Simpson captures these ungraspable moving bodies in outer space, noting that the “shadowy yet glimmering” visual of a meteorite body calls upon the “phantoms, haunting, and apparitions” that the objects allude to—namely the experience of Ed Bush, a Black man from Mississippi who felt the sensation of a meteorite falling near him in 1922. In archival recordings of this rare event, Bush is barely mentioned—he is a ghost haunting what we know about these mysterious galactic rocks.12

The double-sided entrance to the gallery is flanked by bookend paintings: Nightmare? (2015) and True Value (2015). Both massive paintings revisit Simpson’s earlier collage work in which she complicates the human form—placing a cheetah’s head on a woman’s body and the woman’s head on her pet cheetah’s body—and remixes the works to play with brush texture, dark and bleak backgrounds, and blue and grey color palettes. Of all the works in the exhibition, Nightmare? felt the most haunting. The subject’s body is a figure from the 1970s horror film Carrie and the face of an unknown model.13 The painting has a grey translucent color palette with visible brushstrokes that wash the background with variants of white, light grey, and charcoal. From a distance, the strokes read as waves or clouds. In the center is a thin figure that mostly blends into the background. The haunting figure floats. On top of the figure’s body is a square box that holds a feminine face with dark eyes and 1980s teased hair. This glamour portrait shot is printed in high contrast, emphasizing eyes that pierce the viewer.

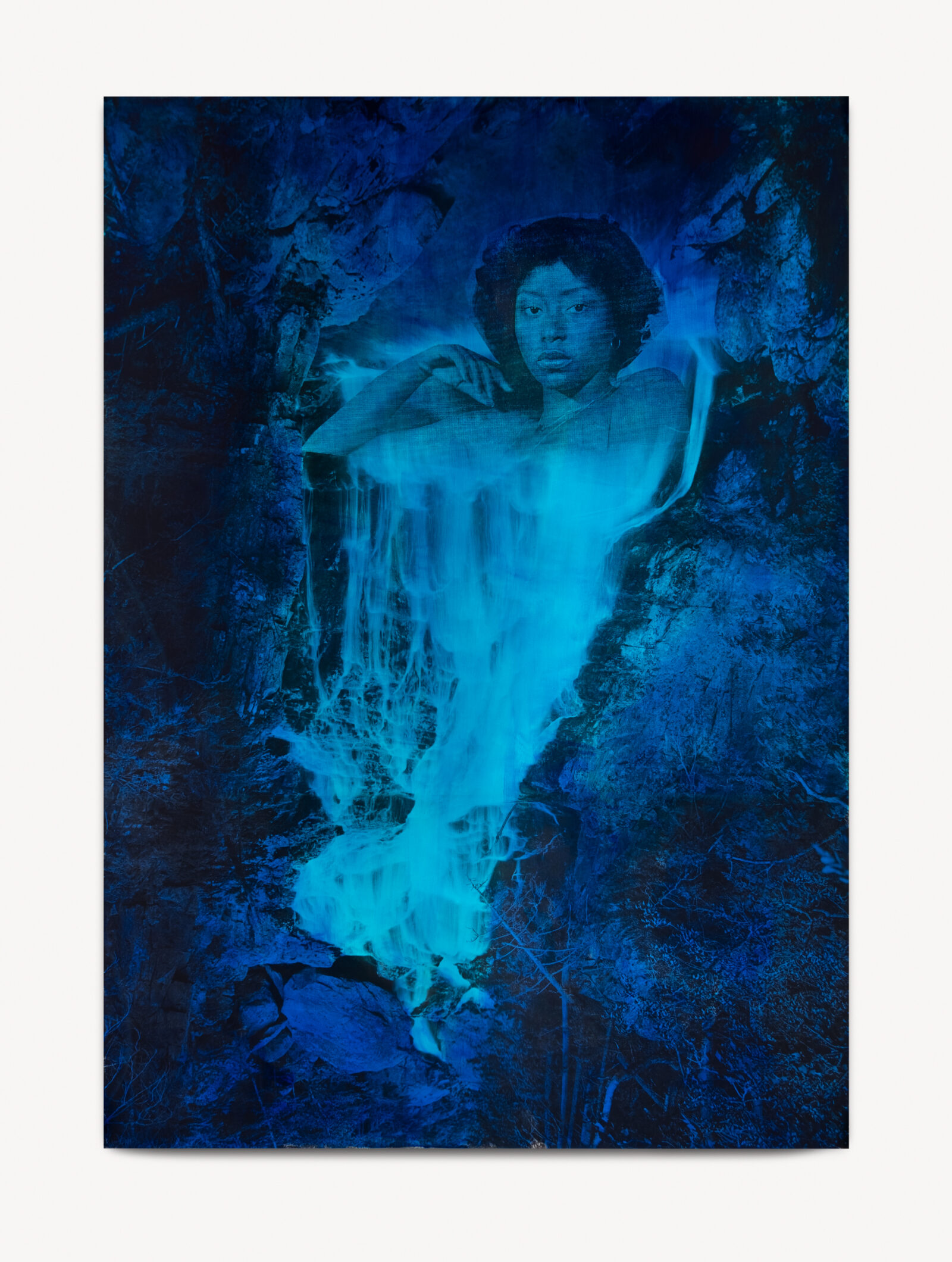

The collaged paintings show Black women’s faces peering out of mountainous cliffs, bodies of water, and cloudy skies. This adds complexity to representing the racial and gendered subjectivities of Black women showing Black women subjects revealing themselves on their terms. Specific Notation (2019) is an ink and screen print of a Black woman seductively looking out to the viewer. We can only see her face partially. Her eyes, nose, and top of her forehead peak out from underneath the textures of dirt and rock. Specific Notation mirrors Night Fall (2023) on two freestanding walls, respectively. Night Fall shows a Black woman with feathered short hair and full lips looking down towards the viewer with soft, firm eyes. We have visual access to only the head, neck, right arm, and shoulders of her body. The lower half of her body becomes a cascade of lava. The bright blue streams are blurred and made translucent with fog and light, making the painting glow. The stream flows down a rocky mountain. The light glows all around her making her even more powerful and godly. The blues, blurs, and calm-yet-piercing gaze feel sincere although she is surrounded by what I would assume to be frightening conditions.

In two long, curved display cases are original collage prints, the earliest dated in 2010 and latest 2023. I felt time resurface for me when I saw Reunite & Ice #1 (2014). Several years ago, I was first introduced to Lorna Simpson through a reprint of this collage of a brown skin woman with a smirk that lifts her left cheek slightly, as if she has just made a quip. Her cunning eyes look up at the viewer with matching amusement. Her neck is adorned in white gold jewels and on top of her head is a crown made of mountainous terrains and rocks. This is the print that made me follow Simpson’s career and was an impetus to my curiosity in Black feminist aesthetics. This nostalgia was a personal haunting.

Lorna Simpson: Source Notes allowed me to come face-to-face with hard feelings around unknowability and opacity while still feeling held, witnessed, and safe. The powerfully large-scale elusive visuals, translucent objects, partial view of bodies and texts, and the spectrum of high contrast and blurs had me wondering about the larger story. What is being summoned to haunt my present moment?

: :

Endnotes

- Lauren Rosati, the exhibition’s curator, notes Simpson’s reference to Black explorer Matthew Hensen’s expedition to the North Pole in the early twentieth century. In keeping with the period’s racist attitudes, Hensen was not credited for his labor and genius on this groundbreaking journey. See Lauren Rosati, “Accumulations: Lorna Simpson’s Paintings,” in Lorna Simpson: Source Notes, ed. Lauren Rosati (New Haven: The Metropolitan Museum of Art and Yale University Press, 2025), 16.

- Alongside archival materials from institutions like Library of Congress and Associated Press, Simpson also treats her family home as an archive and makes use of material from her grandmother’s old magazines and photographs. See, Rosati, “Accumulations,” 19.

- Many critics and scholars see Simpson’s conceptual work as a refusal to be surveilled and publicly known, which contrasts with a white-supremacist art world that craves “images of black folks that reinforce and perpetuate the accepted, desired subjugation and subordination of black bodies by white bodied,” as bell hooks writes about Simpson’s innovative photography. See bell hooks, Art on My Mind: Visual Politics (New Press, 1995), 96. See also Nika Elder, “Lorna Simpson’s Fabricated Truths,” Art Journal 77, no. 1 (2018): 30–53. doi:10.1080/00043249.2018.1456248.

- The research technique of finding the untold stories of Black people’s involvement in historical events—like meteorite discovery and polar expeditions—is a primary focal point when scholars and critics engage with Simpson’s work. This also extends to her repurposing of images from archives that honor Black feminine cultures and interior life. See Adrienne Edwards, “Lorna Simpson’s Voluptuous Intrigue: A Meditation on The Thing,” in Lorna Simpson: Source Notes, 151.

- Furthermore, Alexander notes that the elusive, transparent visuals make clear that “Black women are unfathomable.” See Lorna Simpson and Elizabeth Alexander, Lorna Simpson Collages (San Francisco: Chronicle Books, 2018), Chapter 1.

- Edwards, “Lorna Simpson’s Voluptuous Intrigue: A Meditation on The Thing,” 151.

- Others have noted a felt presence of ghosts in Simpson’s work. See Lauren Rosati, ed., Lorna Simpson Source Notes and Minna Salami, “Meditations with Lorna Simpson,” MsAfropolitian, June 27, 2013, https://msafropolitan.com/2013/06/meditations-with-lorna-simpson.html.

- Speaking of Simpson’s early photography specifically, hooks suggests that Simpson offers a “technology of the sacred that rejoins body, mind, and spirit.” I argue that these ghostly, speculative technologies extend to Simpson’s painting practices as well. See hooks, Art on my Mind, 98.

- In terms of speculation, Simpson discusses the implied narrative or fictions that the visuals evoke. That is, she makes viewers aware that there is a hidden story underneath the representation, but she doesn’t suggest that anyone can know the story as fact or non-fiction. This method of archiving is similar to “critical fabulation,” an archival storytelling methodology developed by Saidiya Hartman who insists that there are more to the stories of archival images of Black life than what the anti-Black archives tell; however, we don’t have access to the stories. We can only imagine them. See Heidi Zuckerman, “Daring as a Woman: An Interview with Lorna Simpson,” The Paris Review, November 10, 2017, https://www.theparisreview.org/blog/2017/11/10/daring-woman-interview-lorna-simpson/, Rosati, “Accumulations: Lorna Simpson’s Paintings,” 165. Saidiya Hartman, “Venus in Two Acts.” Small Axe : A Journal of Criticism 12, no. 2 (2008): 1–14. doi:10.1215/-12-2-1.

- Marjorie Pryse and Hortense J Spillers, Conjuring: Black Women, Fiction, and Literary Tradition (Indiana University Press, 1985), 3.

- Black feminist studies have taken to hauntology as a theory and methodology that concerns Black artifacts, geographies, and spaces that hold Black aliveness but also reveals a systemic and anti-Black power dynamic that keeps some Black life hidden. Scholars employ and retheorize Derrida’s hauntology in Black feminist perspectives, suggesting that such theory speaks to the ways we can feel into Black women’s past that resurfaces in opaque and liminal ways, making it more felt than concrete. See Anique Yma Jashobac Jordan, “Possessed: A Genealogy of Black Women, Hauntology and Art as Survival” (Master thesis, York University, 2015), 16, MES Major Paper (10315/34846); Vanessa Lynn Lovelace, ““The Rememory and Re-Membering of Nat Turner: Black Feminist Hauntology in the Geography of Southampton County, VA.,” Southeastern Geographer 61, no. 2 (2021): 130–45. doi:10.1353/sgo.2021.0010.

- Edwards, “Lorna Simpson’s Voluptuous Intrigue: A Meditation on The Thing,” 184

- Lauren Rosati, Lorna Simpson Source Notes, 16.