According to director Paul Thomas Anderson, One Battle After Another is not a political film. Like its inspiration, Thomas Pynchon’s 1990 Vineland, the film’s 2 hours and 40 minutes are packed with action, chaos, guns, and sinister nemeses. But ultimately, Anderson says, the film is about fatherhood, and as one critic has observed, “The relationship between a middle-aged radical and his daughter is nearly the only element of Pynchon’s novel he retains.” Nor is the film, according to the stance reiterated during its press tour, either right-wing or left-wing. Instead, it’s more generally about extremism, without any particular flavor. As Leonardo DiCaprio, who stars as the father, stated in an interview with the BBC: “there’s an interesting undercurrent about extremism . . . It’s political without making it feel like medicine.” Thus flattened, the film’s depictions of state-sanctioned violence, underground factions, and an elite-run, secret white supremacist group all belong to the same agnostic category.

Perhaps the film’s promotion as non-political or as a timeless personal story is a media strategy designed to avoid scrutiny of the cast’s politics—including DiCaprio, whether spotlighted for his serial dating of women under 25, for his attending Jeff Bezos’s lavish wedding while claiming to be an environmentalist, or for his co-financing a luxury hotel project in Israel while many Hollywood actors and directors have pledged to boycott Israeli film institutions. And yet there is also something accurate about saying the film is neither left nor right per se. Its politics are more reliably about race—and if, as Anderson puts it, quoting one of his characters, “Sixteen years later, and the world has changed very little,” that’s because anti-Blackness is as timeless a story in the United States as fatherhood.

In moments like the car scene where Perfidia (Teyana Taylor), the character Anderson is quoting, kisses Pat (Leonardo DiCaprio) and says “He likes Black girls,” the film underscores how, to borrow a formulation from Zakiyyah Iman Jackson, “the black body is an essential index for the calculation of degree of humanity and the measure of human progress.”1 And because this film has at its center violent politics, armed resistance and sexual enigma, the imaginary surrounding Black politics was seen as the obvious choice. Along with their friends, Pat and Perfidia are members of the leftist revolutionary group the French 75, and they work with their friends to liberate immigrants from detention centers through armed revolt. In the opening scene, Perfidia proceeds to sexually humiliate the U.S. commanding officer, Steven Lockjaw (Sean Penn). Propelled by the adrenaline rush, Pat and Perfidia become lovers, and Perfidia is depicted as driving their sex life through her insatiability. Here Perfidia is the Jezebel, embodying promiscuity, as a demonic temptress capable of awakening the vilest instincts from within the recesses of innocent whiteness.2

What that Jezebel trope ensures is that Perfidia could not herself be innocent, or a victim of sexual harm. From the beginning of the film, rape is treated as a non-question, draped in absurd comedy. In an interview with The L.A. Times, Anderson describes the scene in which Perfidia initially confronts Lockjaw: “It’s a good feeling because we’ve got a real intense vibe going there for a second, some sneaking around the edges. We don’t really know what’s going on. And then suddenly, out of the blue, we’re in boner world. And you’re like, ‘Wait. We’re doing boners too?’ And it’s like, ‘Yeah, we’re going to do boners.’ You have to let the audience know, hopefully in the first act, what the parameters of the playpen are going to be. And that was a clear signal that we’re setting up a real wide berth.”

Later, Perfidia meets the villainous Lockjaw at a motel, and next thing we know, she is pregnant and gives birth to Charlene, whom she abandons to continue her operations. Even if it functions as a plot twist, an attentive viewer will suspect that Charlene could be Lockjaw’s daughter (especially after Lockjaw goes out of his way to press Pat on the issue). Toward the end of the film, when Lockjaw explains that he was “reverse raped by Perfidia,” he communicates an understanding of the “natural order” of rape, as the condition of violence applied to non-male bodies. His formulation also revises what we know about the motel scene. Perfidia’s “agreeing” to the meeting with Lockjaw hinges on her facing the non-choice between the motel or being captured. The constraint and sexual violation of the situation is obscured, not by the comedic aspects of the script, but by the mise-en-scène of BDSM practice. Her performance of the dominatrix role aims to disarm coercion and imply consent, thus constructing a two-way racial fantasy.

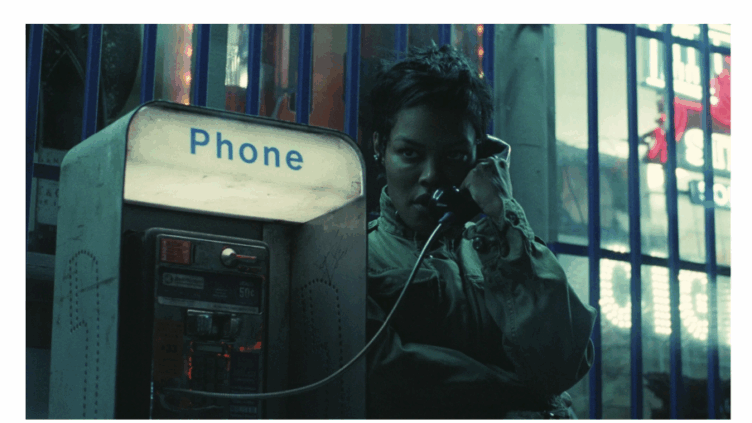

The hypersexualization of Perfidia excludes her from the realm of sexual abuse victimhood. Although Lockjaw has the military complex at his disposal, the deterritorialization of the motel room actually reverses Perfidia’s position from powerless to perpetrator, thus insinuating a war conducted on equal footing—“Black pussy” versus “the largest army in the world.” A later scene in which Perfidia is arrested at the hospital, in a wheelchair and surrounded by chanting, recalls images of Angela Davis or Assata Shakur’s arrests, and their subsequent placement in men’s facilities, where they recall that the threat of rape as punishment was constant.3

In The Libertine Colony: Creolization in the Early French Caribbean, Caribbean studies scholar Doris L. Garraway offers a sophisticated framework for understanding Creole ideology by analyzing the Description de la partie française de Saint-Domingue, a work published between 1796 and 1798 by the white Creole lawyer and statesman Moreau de Saint-Méry. Garraway argues that “Moreau portrays the mulatto woman as the imagined endpoint of reproduction . . . This representation installs a powerful logic of filiation, according to which white men are the real and symbolic fathers of the subaltern races in the colony. Insofar as it legitimates white political authority in the colonial imagination, the filiation allegory constitutes what I call a ‘family romance’ of racial slavery.”4 Similarly, in One Battle After Another, Pat is the character shown caring for baby Charlene, while Perfidia faces what seems like postpartum depression. In the world of the film, parental kinship belongs to white men.

Kinship also takes the form of ownership, with Lockjaw’s attempt to disappear his offspring, which threatens his “higher calling” in service of white supremacy. The film’s lesson would not be complete without the final letter, in which Perfidia expresses regret—does she regret motherhood, her methods, or the ideology behind them? Most likely all three. As Saidiya Hartman reminds us in the context of enslavement, Perfidia is “excluded from the prerogatives of birth” and she can simply claim “to transfer her dispossession to the child.”5 This leaves Charlene vulnerable to state capture, underscored when Lockjaw declares: “I can smell it in you.” Charlene becomes the pretense of a battle between fathers: Lockjaw and Pat.

For the remainder of the film, Perfidia is likened to “historical objects that are only spoken of, but do not speak on their own behalf to identify themselves other than the pejorative names they are given by others who possess power over their existences,” as Patrice Douglass puts it in a related context.6 But rather than exploit Perfidia’s apparent unfitness for motherhood, Teyana Taylor’s performance seems to display genuine empathy for the character. She revealed in an interview with Essence: “What I saw was a woman going through postpartum depression and not feeling seen and not feeling heard and feeling nobody’s gonna show up for me, I gotta show up for myself again . . . we have to give her grace and compassion [as] mothers have to deal with their postpartum depression.” This depression does not just separate Perfidia from her child, allowing Pat to become the bearer of family; it also separates her from Black community, allowing Pat, ironically, to become the community’s center. While Perfidia is feeling isolated, Pat is surrounded by a net of Black women who are constructed in relation to, and in contradiction to, Perfidia, including Deandra (Regina Hall), who is portrayed as the more strategic and composed militant, the one who “keeps it together.”

Even if the promotion of the movie—especially on social media platforms like TikTok—largely highlighted iconic Blackness, through appearances by Regina Hall, Teyana Taylor, and Chase Infiniti, the film communicates a white man’s world: the holy trinity of hippie (Leonardo DiCaprio), soldier (Sean Penn), and bourgeois (Tony Goldwyn). The Black characters comprising the multiracial leftist group are never seen in commune with or in service of the Black community, unlike Sensei Sergio St. Carlos (Benicio del Toro) who is placed in “a Latina Harriet Tubman situation.”

On the same day that One Battle After Another was released in theaters, the world learned of the passing of Assata Shakur, a real-life revolutionary who died in exile, estranged from her family, un-incarcerated but not free—because, as Jatella reminds us, “fugitivity is not freedom.” Shakur’s life was lived in the grips of state violence, which restricted her movement, surveilled her, and separated her from her family and culture. And it is this sense of surveillance—omnipresent both in the fictional story of Perfidia and in the real-life story of Shakur—that challenges the cliché that the revolution will not be televised. The question is not whether the revolution will be televised, but whether revolution can happen despite being televised. Perhaps Kendrick Lamar was right to say “the revolution will be televised—you picked the wrong guy for the right time.” For today, both big screens and handheld screens alike capture war crimes, purges, state-sanctioned abductions, and displacement. Despite the cast and director’s insistence otherwise, One Battle After Another does have a politics, crystallized in its final scene: Charlene changes the world, one peaceful protest at a time, while her goofy ex-revolutionary white father fumbles with his brand-new iPhone.

: :

Endnotes

- Zakiyyah Iman Jackson, Becoming Human: Matter and Meaning in an Antiblack World (New York University Press, 2020), 46.

- See Tamura Lomax, Jezebel Unhinged: Loosing the Black Female Body in Religion and Culture (Duke University Press, 2018) and Dorothy Robert, “The Paradox of Silence and Display: Sexual Violation of Enslaved Women and Contemporary Contradictions in Black Female Sexuality.” Beyond Slavery: Overcoming Its Religious and Sexual Legacies, edited byd. Bernadette J. Brooten (Palgrave Macmillan, 2010), 41-60.

- See Assata Shakur, Assata: An Autobiography (Chicago Review Press, 2020).

- Doris L. Garraway, The Libertine Colony: Creolization in the Early French Caribbean (Duke University Press, 2005), 247.

- Saidiya Hartman, Scenes of Subjection: Terror, Slavery, and Self-Making in Nineteenth-Century America (Oxford University Press, 1997), 167.

- Patrice D. Douglass, Engendering Blackness: Slavery and the Ontology of Sexual Violence (Stanford University Press, 2025), 64