Caroline Hovanec’s Notes on Vermin is a book of subtle thought, explored through an exhilarating range of literary and visual sources, interspersed with down-to-earth personal anecdotes. The argument is an unraveling, an “unbinding” of what Hovanec takes to be the “dominant theoretical apparatus of animal studies.” (25-6) That apparatus is, as she describes it, driven largely by the “posthumanist ethical project,” which too quickly inverts humanist values and hierarchies to favor and defend the nonhuman. (24) Vermin expose the insufficiency of those ethics, the insufficiency of a “defense” of creatures that are actually thriving in spite of human efforts to be rid of them; and also thriving because of human ways of life. Making herself an experiential, even confessional part of the book’s investigation, Hovanec’s political and psychological perceptions are often acute. For instance, reflecting on her own “horror of mice”: “My experience of powerlessness gives cover for a rather cruel application of power. It is as if I am saying to the dead mouse, ‘Look what you made me do.’” (9) I found this a disarming admission, exactly eliding the violence that bridges human horror and dead mouse; and it prepared me as her reader to meet that vulnerability with my own. It also prepared me to think about the category of vermin as relational and volatile, and as a question of something that is always very close to home. We don’t have to go out looking for vermin; they are already too much with us.

The “Notes” of the title indicate epistemic modesty, and Hovanec signals at the end of the introductory chapter that she “gestures at some new lines of thought, . . . which I leave it to other scholars to pursue more fully and rigorously.” (26) On the contrary, I found that Notes does rigorously pursue its lines of thought. What I missed more was something like a felt connection between the aesthetic experience of the texts and the striking claims about vermin in the lived experience of human beings, including the author. Somehow those literary vermin kept eluding me in Hovanec’s critical prose, which prompted me to go to her literary sources. Upon reading, for instance, Clarice Lispector’s novel The Passion According to G.H. and Isaac Rosenberg’s poem, “Break of Day in the Trenches,” I wanted more of Hovanec’s own aesthetic perceptions as grounded in the texts—which might have given more flesh to the incipient, erosive theory of vermin that Notes asks us to entertain.

Hovanec’s relative reserve in engaging with her chosen texts follows from what she calls the method of “medium reading” or “medium-distance reading”: arguably how she manages to cover so much ground in such a slim book. Medium distance is “not the machine-supplemented distant reading of the Stanford Literary Lab, or the traditional close reading of literary criticism that would have limited me to four or five exemplary primary sources, but something in between.” (22) It is a compromise, which any critical method arguably involves, and her transparency is refreshing. Yet the deeper I read into Notes, the more I doubted the adequacy of this middle way for taking up both the subject (vermin! after all) and the aesthetic force of the texts chosen as examples. These are not texts I want to keep at arm’s length, if I am to read them at all; or, crucially, if I am to read them for the way they prompt me to think and feel about vermin. The relational character that defines vermin as a category, according to Hovanec’s nuanced theory, is deeply tied to the visceral responses of 20th- and 21st-century humans to verminous animals, to these literary vermin gnawing away at all their generalizations. Perhaps I want the impossible, given the constraints of the book’s length: for the depth of readerly engagement with the texts to correspond with the depth and complexity of the human-vermin relation they are supposed to help us imagine and think through.

I also want to emphasize the perceptiveness of Hovanec’s “verminous thought,” in light of my qualms about her method of reading. One insight struck me particularly: that “surplus life,” so endemic to the very idea of vermin (ever plural), could be helpfully thought of as the dark side of scarcity, endangerment, and biodiversity loss. Hovanec’s example of the passenger pigeon, which went almost overnight from verminous excess to extinction, illustrates this point brilliantly. And her literary example, Louise Erdrich’s A Plague of Doves, is apt. She intervenes deftly in interpretive questions; why, for instance, it doesn’t make sense to equate Erdrich’s doves to white settlers, as other critics have: it is unobservant of the “pinkish-brown feathers of the passenger pigeons.” (108) She understands why other critics have made that move: “doves” popularly understood as symbolic, associated with pure-whiteness, slip into an allegory of (plaguing, therefore verminous) racial whiteness. Yet as she points out, such a tidy allegory neither does justice to the complex cultural realities of indigenous-colonial interactions in the novel, nor to the physical realities of the birds. In such cases, I find Hovanec’s “unbinding,” discriminating approach to other critics’ overzealous equivalences quite beautiful.

I am shelving Notes alongside Ursula Heise’s Imagining Extinction.1 Both books take up overdetermined phenomena that span the nature-culture divide, regarding them afresh and with curiosity through a range of cultural works. Hovanec’s subjects exist in counterpoint with Heise’s, species rampant rather than rare. Yet Heise, for the most part, chooses works that readily yield cultural assumptions about the value humans place on endangered animals: websites, popular fiction, legal texts, graphic novels. (I recall two lyric poems feeling curiously out of place.) Hovanec by contrast mixes registers more boldly, often choosing demanding works of modern and contemporary literature. Mickey Mouse rubs shoulders with Gregor Samsa. Classic modernist poems by Isaac Rosenberg and D.H. Lawrence, but also Bong Joon Ho’s sensational Parasite (2019). Other sources include Samuel Beckett, Charles Darwin, Richard Wright, Mina Loy, blues standards, Clarice Lispector, Namwali Serpell, Rawi Hage. It’s a refreshing opportunity to see things we might miss about works seen only alongside their obvious aesthetic kin.

An abiding insight of Notes:we are caught up with our vermin, inseparable from us. Creatures have independent existence, but their verminous aspect is not biological; vermin only to the one who says vermin. And, I take Hovanec to be saying at least implicitly, literary and aesthetic works let us encounter imaginatively beings we recoil from in reality—an extraordinary capacity of art. “I no longer believe in the political efficacy of the romance of fugitivity,” Hovanec announces at the beginning of the chapter on “Fugitive Movements.” Her critique is trenchant and passionate: this romance “has become a fantasy of disruption, adaptability, and making-do that rather suits the ruling powers of today, the vultures of capital who love nothing more than . . . leaving others to salvage what they can from the scraps.” (53) I agree that how we read and account for literature may be politically efficacious or not; but hasten to add that literature itself might only be so indirectly, or not at all.

Reading, I may come to realize I cannot be rid of my vermin without also getting rid of myself. And the force of this realization does not occur to me as a reader without first entering into a relation with the text. Lucy Alford has suggested, far from guaranteeing any predictable outcome, “that poetic attention can cultivate the necessary but insufficient grounds for ethical response.”2 I often return to that formulation, and bring it to bear now on Hovanec’s question of political efficacy, because I think it catches something important about the energy of such attention, which cannot issue in any compulsory response. Such reserve, I should say, is theoretically in keeping with Hovanec’s claim to “unbinding” rather than building a theory. She, too, asks rhetorically, “is such recognition [of verminous resilience and adaptability] really an ethical encounter across species?” (25) The clearing away of this question might prompt a deeper engagement with literary vermin, yet Hovanec, in the short space accorded to each example, tends to bind the literary texts to other theories than the ones she unbinds them from. In the laudable effort to trace in literary vermin “hopes for a more just, less exploitative way of living together,” some of the strongest, least biddable texts seem pressed into service. (26) Their wings are clipped. I would prefer a method of reading more open to what is entirely unself-evident, unanticipated by theory, about a text like Clarice Lispector’s The Passion According to G.H.

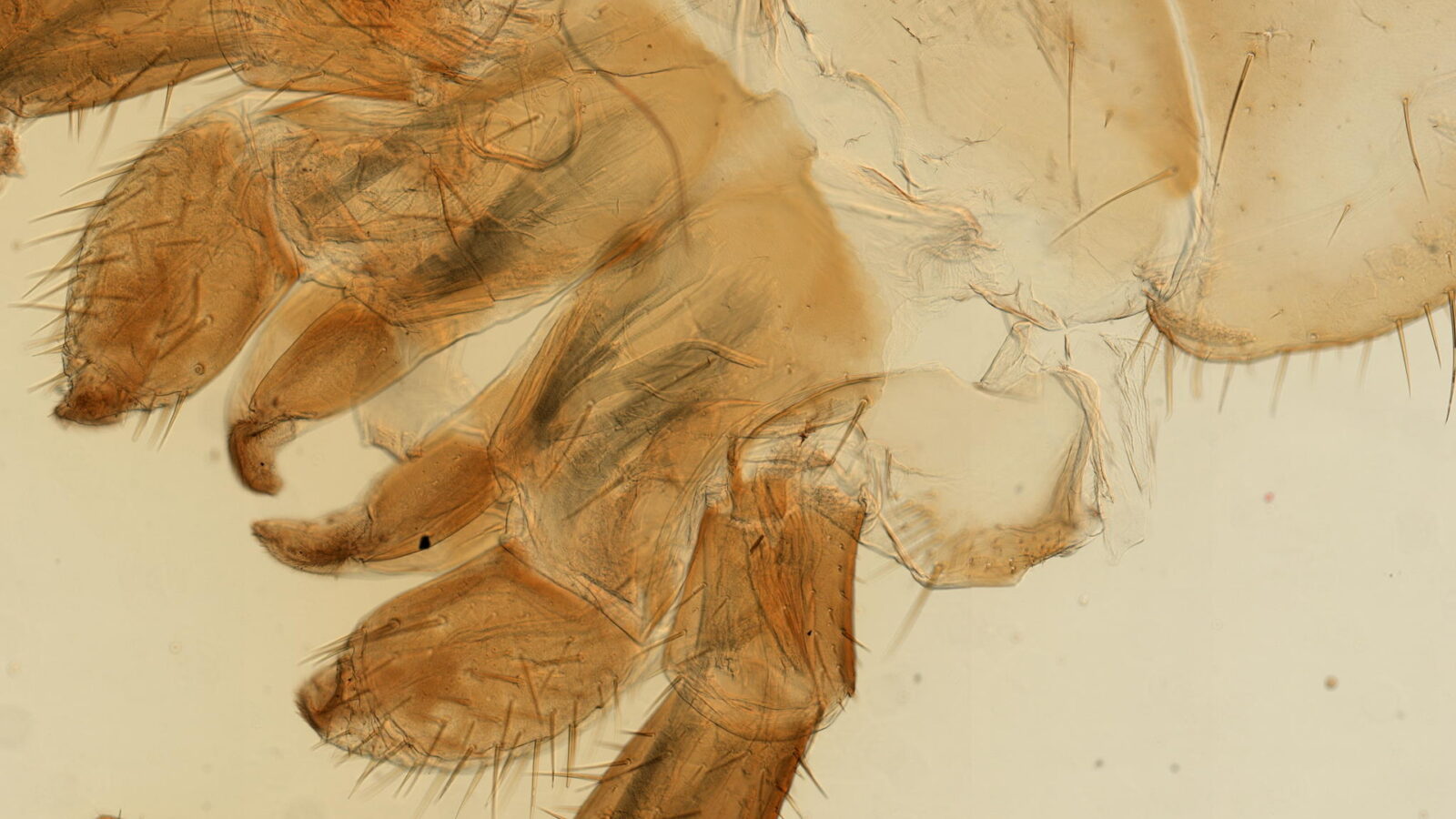

If someone tells me, you are what you verminize, I might think them a clever neologist. But until I encounter Lispector’s prose (vividly translated by Idra Novey), I cannot conceive of the experience of the woman called G.H., arrested, undone by her encounter with a large cockroach. It is hard to give an account of this text from without, relying as it does on an immersive first-person voice becoming passionately first-impersonal. In Sharon Cameron’s sense, impersonality marks “the uncompromising nature of writing about the precariousness of personal identity measured at the moment of its disintegration.”3 A medium-distance reading does not register this terrifying process. Hovanec includes Lispector’s The Passion as an example of bell hooks’s theory of “eating the other,” since G.H. indeed eats of the roach’s insides, slowly spurting out after she slams the wardrobe door upon it; and notes that “hooks’s caution that this sort of consumption can be appropriative, even violent, applies to G.H. in the novel too.” (39) This is the application of theory to literary character in the sense that “hooks’s caution . . . applies to G.H. in the novel.” Too quick to wring a moral from an enigma, I missed in Notes a sense of the novel as primary and unforeseeable.

Hovanec asks whether we’re meant to take G.H.’s “mystical vision” seriously, or as “religious parody,” as Sianne Ngai puts it. (37-8) I submit that the experience of reading The Passion does not allow or oblige us to choose between genuine and parodic, and that the novel is mysterious to the point of demanding a closer than medium-distant reading. In the narrator’s flash of insight into what she calls “the moral problem” and “the moral question,” here is one kind of ethical power a literary evocation of vermin can have:

Ah, at least I had already entered the roach’s nature to the point that I no longer wanted to do anything for it. I was freeing myself from my morality, and that was a catastrophe without crash and without tragedy.

Morality. Would it be simplistic to think the moral problem with regard to others consists in behaving as one ought to, and the moral problem with regards to oneself is managing to feel what one ought to? Am I moral to the extent that I do what I should, and feel as I should? All of a sudden the moral question seemed to me not only overwhelming, but extremely petty. The moral problem, in order for us to adjust to it, should be at once less demanding and greater.4

Sounding like an unhinged Simone Weil, able to send up such shattering thoughts and questionings of the foundations of the things without Weil’s severity, almost with a shrug and a sigh, the narrator pulls the rug out from under “morality.” Not in defense of morality’s opposite, but exposing its insufficiency; a kind of “off with its head!” There is something rousing, something I cannot look away from in the way this narrator lays bare and neutralizes illusions which I also, surely, cling to. Why might it be elating rather than devastating to read: “I am as unreachable to myself as a star is unreachable to me”?5 It has something to do with the experience of individual personality breaking down, a giddiness about the newfound dispersal of presence that comes of the narrator’s “rapidly becoming unaddicted.”6 To what? The novel’s ethical potency, when it comes to the question of vermin that is Hovanec’s subject of study, is bound up with the way it allows the encounter between G.H. and the cockroach to lead to a dismantling and unmooring—parodic and terrifying—of G.H. The encounter does not lead G.H. to take on a merely more respectful, seemlier regard for herself or for this creature—an adjustment which might have been called “moral.”

In an inspired turn towards the end of Notes, Hovanec picks up the etymological root of “vermin” as “the Latin vermis meaning worm.” She reads Charles Darwin’s final book, The Formation of Vegetable Mould through the Action of Worms, and one of Samuel Beckett’s wormy narrators (of How It Is) in succession. She is, I found with pleasure, a lively reader of Darwin, particularly of the “Darwinian lineage” attuned to “nature as a comedy of errors, and error as fundamentally generative.” (122) This comment beautifully echoes the “miniature comedy of errors” in Hovanec’s reading of Kafka’s The Metamorphosis, with which she opens her investigation. (6) She offers the Darwinian lineage in the end as one alternative to the too-easy inversion of the human relation to vermin she finds in the “dominant theoretical apparatus of animal studies,” and I am convinced. I am convinced that vermin expose human errors: errors which can be catastrophic, yet unaccountably comedic.

I wish the book could have been longer, and that Hovanec had more frequently come closer to her literary sources than medium-distance. For then her wry personal anecdotes might also have had more to do with her critical insights. To convert circuitous, sensuous literary creations into something “politically efficacious” bypasses the peculiarities of aesthetic experience. These are the primary qualities of literature which draw me, at least, into these created worlds in the first place; to linger in the presence of creatures I might violently, almost involuntarily, reject in daily life. Not so that I therefore welcome bedbugs into my bed, cockroaches and rats into my kitchen . . . the therefore is never so ready to hand.

: :

Endnotes

- Ursula Heise, Imagining Extinction: The Cultural Meanings of Endangered Species (University of Chicago Press, 2016).

- Lucy Alford, Forms of Poetic Attention (Columbia University Press, 2020), 277.

- Sharon Cameron, Impersonality: Seven Essays (University of Chicago Press, 2007), 6, ProQuest.

- Clarice Lispector, The Passion According to G.H., trans. Idra Novey (New Directions, 2012), 84-5.

- Lispector, 127.

- Lispector, 104.