Think of Me When It Thunders, exhibition

C L E A R I N G Gallery, Los Angeles

18 February, 2025 – 5 April, 2025

: :

I was walking by Los Angeles’ CLEARING gallery when I felt a pull to stop: a subtle thumping sound beyond the door drew me in.

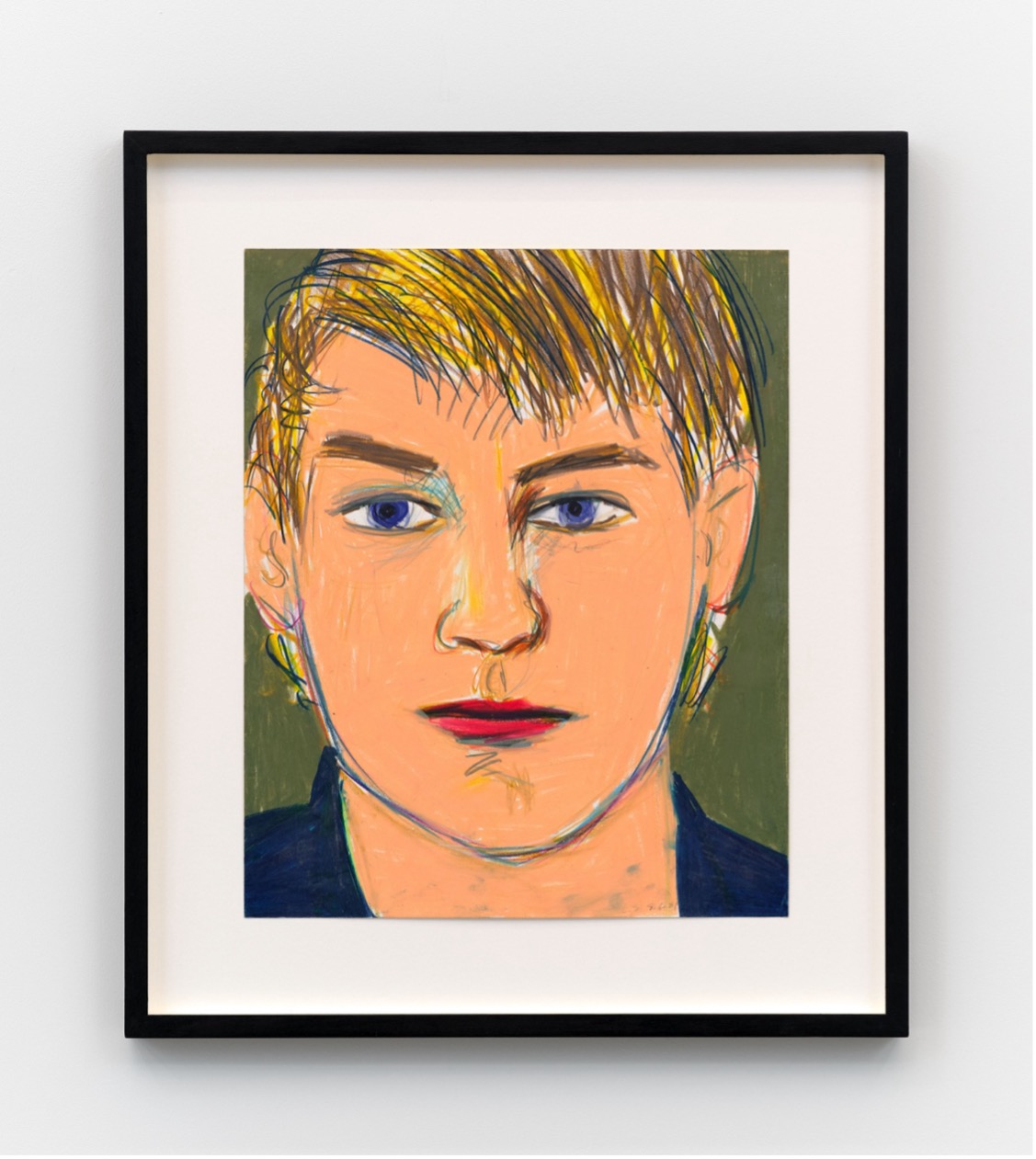

When I opened the door and entered the airy space, a pair of piercing blue eyes and rhythmic disco music greeted me. Artist Larry Stanton’s (American, 1947-1984) conte crayon Self-Portrait (1981) was captivating. Dirty blonde hair, each singular yellow and brown colored line melding into a golden tousle, sweeps across Stanton’s forehead, framing those mesmerizing eyes. His bright red lips posed, possibly ready to speak. What words do they want to offer us? Whisper a secret? A bit of gossip?

Think of Me When it Thunders is Stanton’s first exhibition on the West Coast of the US, and consists of thirty works made between 1980-1984, most of which were portraits of men. The works are made with colored pencils, pastels, crayons, and acrylic, offering a vibrancy of colors and textures.

Known for his portraits, the works evince Stanton’s particular and various relationships to each of his subjects. Sitters for his portraits included one-night stands, romantic partners, and dear friends; the boundaries between these relationships blurred. Embedded within the brushstrokes, crayon shading, and gliding lines of each portrait are the (imagined) interactions that comprised Stanton and his sitter’s relationship, such as the laughter over an inside joke, the fleeting glance at one another on a busy street that confirmed desire, or the welcomed drollness of stories repeated among close friends. The interpersonal connections between Stanton and his subjects are just as essential to the portraits as their formal qualities.

Stanton was known as the “it boy” in the bi-coastal gay and art scenes from the late 1960s until his death. He befriended artists such as David Hockney and Ellsworth Kelly. While he created affectionate works about this circle of friends—as in a video piece David Hockney at Ken Tyler Graphics (1978) which depicts Hockney working on his iconic pool paintings—his portraits of one-off encounters exhibit the same sense of tenderness and vibrancy as those of his friends and closer lovers.

While the works included in Think of Me When It Thunders illustrate the range of relationships Stanton had (and one can make the case that these dynamics reflect the relationships that compose our own lives), they act as a record. Most of the men who sat for Stanton died prematurely from AIDS.

Together, the collected portraits in the exhibition pose a particular question: How does one want to be remembered when one passes? For their actions? Their work? A series of objects that they collected, or ones that represent them? What might continue to evoke a person when the physical is no more? “I know,” desired Stanton to his long-term partner, Arthur Lambert, Jr., as Stanton lay in the hospital dying from AIDS “think of me when it thunders,”1 Stanton, who would pass at the age of 37, worried about how time would slowly erase him from the memories of those who loved and cherished him. In claiming the booming of thunder, the weather would perform an act of resurrection for Stanton’s spirit. Experiencing thunder becomes a full-body encounter: from the rumbling in one’s ears to the reverberation through the body. When it thunders, Stanton is evoked in both the natural world and the corporeal.

But as Lambert lamented, “it doesn’t thunder every day.”2 Though it may not thunder every day (especially in Southern California), the reverberation and repetition of remembering Stanton wished for can be felt in his works. Think of Me When It Thunders is an archive and memory of lives lost to AIDS, and I want to position the works themselves as the sound and rumble of thunder Stanton was evoking. Rather than the static notion of an archive, Stanton’s works contain an affective dimensionality that, as Arjun Appadurai has conceived, presents the archive as an “aspiration rather than a recollection.”3 In this, the works are a continual form of active memory building. In their countless displays, the pieces act as that form of memory-as-thunder that Stanton had sought after.

Most of the works in the show are titled intimately and casually, using first names, such as Patrick (1980), while others include their subjects’ full names, as seen in Stanton’s lover’s portrait Arthur Lambert (1984). Others remain untitled or generically descriptive. In Two Men (1980-1984), a large work that remains unframed among a series of framed portraits, these unnamed figures are imbued with a soft aura. A blonde man in the background is presented in profile, capturing the subtle shadows of his facial features. He seems to be looking away from a dark-haired man who poses in the foreground. The dark-haired man makes direct eye contact with the viewer. While it is unclear who these men were in relation to Stanton, or whether they knew each other, Stanton captures a subtle connection between them.

In one pencil drawing, Philip (1983), the titular man dozes in a wooden deck chair. The lines are soft; the sun’s warmth can be felt across his face. An undone tie hangs around his neck. In the foreground, a hand extends forward with a pencil, drawing the same view of Philip on another piece of paper. A work-in-progress of sorts, Stanton invites us to sit with him as he works and find the softness within this moment.

While Stanton created these works under the looming presence of loss, both for himself and his sitters, his portraits navigate the terrain of AIDS with a depth and dignity often absent in other representations of the time, which ran the risk of reducing their subjects to mere victims or vessels of the virus. This dilemma of capturing people with AIDS (PWA) has been grappled with by art critic/historian and AIDS activist Douglas Crimp (1944-2019). Photographs of PWAs were replicating particular tropes, presenting them as “ravaged, disfigured, and debilitated by the syndrome; they are generally alone, desperate, but resigned to their ‘inevitable’ deaths.”4

What frees Stanton’s works from this narrative is the vibrancy of the material markup and the felt relationship embedded throughout each of the portraits.

Rather than a chronological ordering, the exhibition places the portraits in community with one another. The works speak among themselves, staring at one another not as voyeurs, but in knowing ways. As one stands among the intersections of sight from the names and untitled portraits, you become quickly enveloped in their silent dialogues. Omar (1983), a piece whose sitter’s eyes hold such emotion, gazes directly across the gallery to two Untitled line works of men lying on their stomachs in a bed with their pants at their ankles. Their asses are exposed. Perhaps they are resting, but it is likely they are attempting to entice. Do they interest Omar? Possibly. But they may also be Omar at some point in his life. Does he whisper his memories to them?

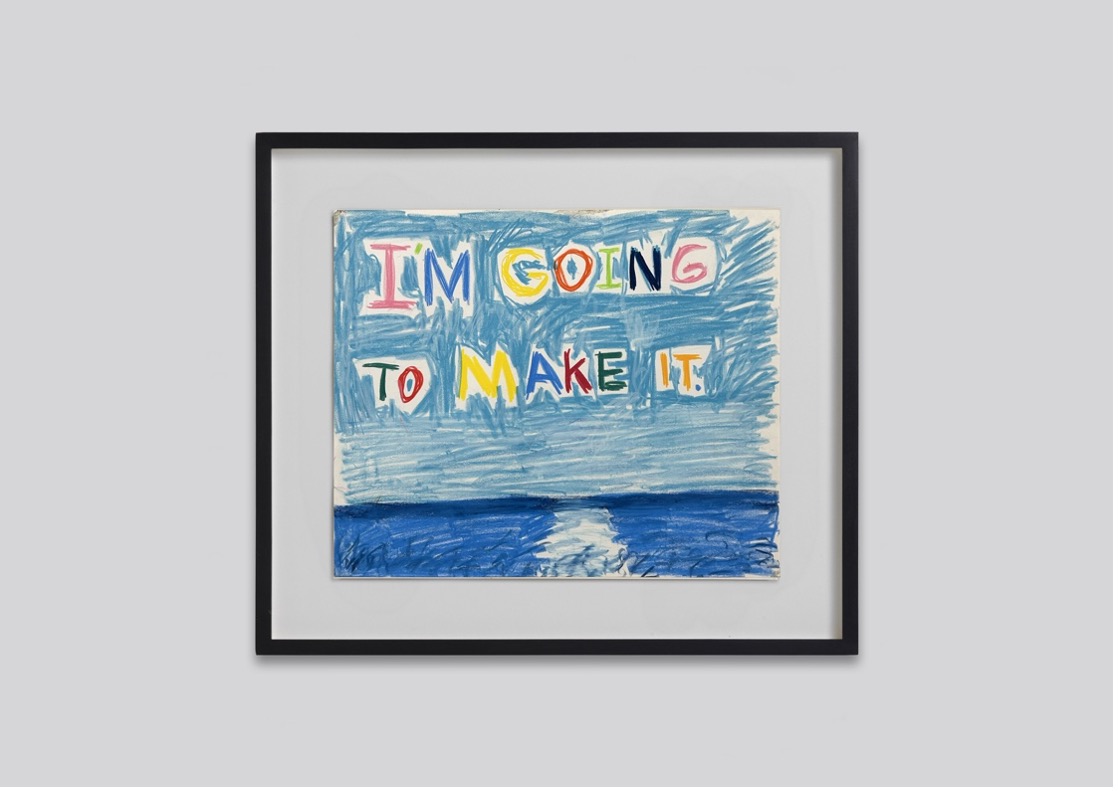

One of Stanton’s final works before his death is placed by itself on the expanse of white wall. A deep blue body of water ripples beneath an expanse of sky. Created in crayon, the work’s scratchy surface moves with the buoyancy of water. Embedded into the sky is the phrase “I’m Going to Make It,” created from various pinks, blues, yellows, reds, greens, and oranges. Either a hopeful wish or a determined statement about Stanton’s career posthumously, the phrase captures what may have been sitting behind Stanton’s lips in his Self-Portrait.

As I walked through the gallery, the synthesized repeating vocals of the music that initially drew me in — Cerrone’s Supernature (1977) — were punctuated by a saxophone as Evenlyn “Champagne” King’s Shame (1977) seamlessly took Cerrone’s place. This mix of songs could have pulsed through the clubs or dance floors that Stanton moved across, or played on the radio as he sat across from his sitter. Echoing now through the gallery, they helped craft the idea that these portraits were very much together in a shared historical and present moment of camaraderie. The gallery space might not quite be the dinner parties or get-togethers that once occurred, evident in a series of Polaroids in the middle of the gallery, but the curation preserves a similar uninhibited and euphoric dancefloor energy.

Writing this review after the exhibition has closed is a testament that Stanton has indeed “made it” as he promised us and himself in his self-portrait. But it is not just himself, rather the community he immersed himself with, that continues. The relationships he fostered, whether brief occurrences or deep dynamics, endlessly appear and are felt throughout Think of Me When It Thunders. Each time the works are hung, even just a single one, the hope of “making it” is manifested and fulfilled. And being more than just a record of those who have passed, Stanton has offered a celebration of life and relationality.

Think of Me When It Thunders is a continual rumble for not only Stanton, but also for those strangers, friends, and lovers he intertwined himself with.

: :

Endnotes

- Arthur Lambert, Jr., Larry Santon: Painting and Drawing (Pasadena: Twelvetrees Press, 1986), 69.

- Lambert, Jr., Larry Santon: Painting and Drawing, 69.

- Arjun Appadurai, “Archive and Aspiration,” in Information is Alive, eds. Joke Brouwer and Arjen Mulder (Rotterdam: V2 Publishing/NAI Publishers, 2003): 14-25.

- Douglas Crimp, “Portraits of People with AIDS,” in Cultural Studies, eds. Lawrence Grossberg, Cary Nelson and Paula A. Treichler (New York and London: Routledge, 1992): 118.