The human experience of loss (through whatever means) is precisely what it appears to be: an intolerable deprivation, a vacantness—a lack. Loss of one person frequently begets the loss of another (a constitutive trope of antiquity’s tragedy: loss compounding). Sudden spousal death oftentimes, however indirectly, kills the surviving partner. The death of a loved one spurs suicidality. A dead parent or sibling is an irrevocable hole for the remaining child or sibling. A loss in one’s life invokes the recognition of a certain barrenness implicit to reality; this recognition of a void, an always-already emptiness, is mourning. The loss of oneself (in terms of death or lack of investment in life), due to the loss of another, is melancholia.

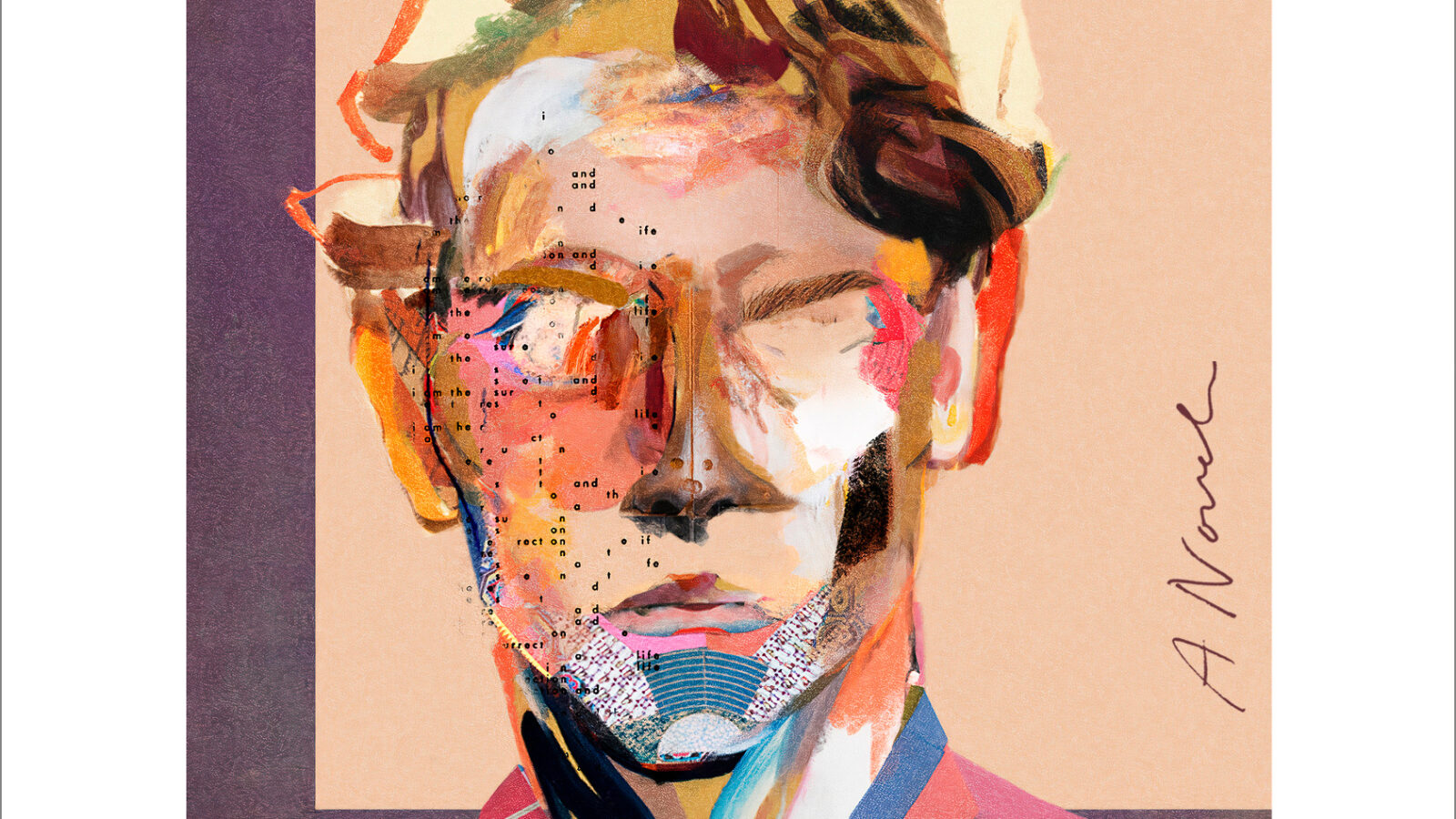

Sophie Madeline Dess’s recently released novel, What You Make of Me, convincingly articulates art’s role in mourning—exhibiting that loss is never entirely individuated, always presupposing a public. The novel, centering on two siblings—a sister (Ava), an artist, and her filmmaker brother (Demetri) who writes about, interprets, and promotes her work—is written like a narrativized exhibition catalog. The exhibition pieces, drawn by Ava of her dying brother and derived from their lives, are described through the novel’s prose in concise footnotes.

The book begins with the narrator anticipating a traumatic loss that has already begun: “In two weeks they’ll be killing my brother” (1). Demitri, the narrator’s brother, has fallen into a coma from brain cancer. The loss of her brother (the point, temporally and psychically, when a presence becomes an absence) began nine months ago, at the start of his coma.

The novel chronicles their inextricable lives—from a turbulent, dually interdependent childhood to a sometimes-contentious adulthood marked by occasional jealousy and even mutual love interests. When Demetri enters the coma, towards the end of the novel, Ava aptly analogizes his comatose state to his anticipated death: “deep into the night, with a sound as soft as breath ceasing, my brother’s brain stem torques, twists inward, forever isolates him into a deeper shade” (274). The transitional moment when Dimitri slips into the comatose state is as “soft” as “breath ceasing.” The collapsing of death and coma is undoubtedly not incidental: Demetri’s coma marks the site of an absence, a loss preceding death; a loss with death’s same finality.

In his 2008 book, The New Black, psychoanalyst Darien Leader writes that Sigmund Freud’s seminal essay, “Mourning and Melancholia” misapprehends a necessary dimension of mourning. Despite broadly agreeing with the Freudian classifications of loss (mourning as a process one moves through, eventually releasing the lost object; melancholia as a static position emptying the ego), Leader explains that, for Freud, “[m]ourning is treated as a private event. . . the individual is alone with their grief.”1

In contradistinction to this classic psychoanalytic view, Leader posits that mourning is predicated on “formalized public displays and the involvement of the community.”2 Cross-cultural experiences of grief and loss appear to corroborate this—when people inscribe gravestones in public cemeteries with names and symbols so that strangers can identify the dead, when we refrain from speaking ill of the dead, when we repeat the reiterated performance of funerals for an audience of mourners.

According to Leader’s conception of mourning as a public act (rather than relegated to the private sphere of individualexperience), art occupies a privileged status: Art is a transpersonal representation that converts mourning into a “model of creation,” an instrument “to help us mourn” through recognition of loss.3 He writes, “[art] shows us not just a loss but how something can be created from loss.”4 The inexplicable becomes explicable; a lack is converted into an artistic designation from which the loss can be affirmed through externalization.

Dess demonstrates the public mourning function of art in her book: the loss of Ava’s brother spurs her to paint, creating enough work for her first solo exhibition. Each painting is derived from a scene of their lives—and taken together, they are repeated representations of the object of Ava’s loss, her brother. One could appeal to platitudes about memorializing—about attempting to forever embed the dead into consciousness—but Ava’s compulsion to represent her lost sibling exceeds memorialization.

Leader claims that in the process of mourning, “our memories and hopes about the one we’ve lost must be brought up in all the different ways they have been registered, like looking at a diamond not just from one angle but from all possible angles, so that each of its facets can be viewed.”5 Ava’s artwork could be understood in Leader’s terms, in a temporal, spatial, and material sense: her paintings of Demitri proliferate from different times in his life, different angles (his smile under a disco light, his pupils, even his farts), and disparate mediums and materials, from oil on linen to acrylic on canvas. One is titled “Fearful”—another is “Openmouthed, full-toothed grin” (96).

At the end of the book, which merges narratively with the beginning, Ava is at the threshold of a passage from an exclusively private mode of mourning to its public display (the moment between privately painting and publicly exhibiting the work). Is this public facet of creation not superfluous? Hasn’t the loss been ‘worked through’ via the creation of the paintings themselves?

No, because the loss must be registered beyond herself—public, symbolic gestures of loss are the precondition of mourning. The book’s form, as an exhibition catalog, invokes precisely this principle of mourning. Dess shows the mourner’s need to control the public gesture of loss, by describing Ava’s need to perform this public act of describing the work: “[the gallery] will not be trifolding me and my dying brother into that little catalog. I’ll do it myself” (3). The novel is itself a written symbol of loss.

A crucial moment in the text helps Ava’s movement towards “productive” mourning and away from being anchored in the frozen immobility of melancholia: While Demitri is in a coma, his child is born and this birth brings a person who, while not exactly taking Demitri’s place, can facilitate her recovery of reality by making her engage with new life after his death. Dess ends the book with Ava reflecting on Demitri’s baby, thinking to herself that she will “make him into something” (278) as she did her brother, and her brother did for her.

Dess observes that this baby, like all babies, “has no history . . . no habits, and so he is unknowable” (278). A new purpose emerges here: to concurrently come to know the baby and to make that baby who they will be—she must create an “image” out of the other.

By the end of the book, Ava finds herself at the precise fork between productive mourning and self-annihilating melancholia: exhibiting the work, and forming an attachment to the child, are the means to a mourning that allows for the continuation of her life. However, What You Make of Me is irreducible to a clinical case study: the novel offers a different, more particular understanding of the relationship between artistic production, mourning, and meaning. While the narrative centers on the exhibition pieces of Demitri, there is a second nexus of the text: Demitri’s posthumously released documentary about Ava as an artist.

In Demitri’s film, representation does not emerge from loss—but rather directly from a presence. Ava, the subject of the documentary, is alive as he creates it. Although never fully described in the text (since Ava does not watch it), there is a scene of her painting in slow motion—the penultimate attempt to capture another, slowed frame by frame. Taken together, these two representations are the “makings” that the novel revolves around.

What is the place of art in the “making” of another—especially as they are still living? “Making another” takes on a dual meaning: making something of another (creating a representation of another) and making someone into something (forming who someone is). Attempts to understand others through representation are antecedent to losing them—and these attempts to represent while one is alive, are concomitant, if we have true proximity to them, with making them who they are. The paintings of the exhibit and the documentary are making something of another—representing them; the written narrative of Ava and Demitri’s lives are the making someone into something—taken together, they form the coordinates of knowing, and mourning, another. The sprawling, opaque darkness of another perpetually eludes definitive representation while living (even if we help make another who they are)—and death only compounds the other’s opaqueness.

When Demitri proposes the idea of a documentary about Ava, she tells him that “a documentary would be too literal an expression. It would not work” (98). A documentary, like a painting (or any symbolic representation), is too static and can never totally capture the elusive other. Yet, as the novel reminds us, representation remains all that we have at our disposal.

Here, Dess writes a novel that appears to agree with Leader on death and loss: the best a human can do (and being human necessarily entails being a mourner) is engage in the (necessarily failed) project of exhausting all the representations of another—to try to index that which is lost. Until then, the dead cannot die, and the loss will implacably haunt us, impeding the ability to mourn and eventually negating life itself.

: :

Endnotes

- Darien Leader, The New Black: Mourning, Melancholia, and Depression (Graywolf Press, 2009), 71.

- Darien Leader, The New Black: Mourning, Melancholia, and Depression, 71.

- Darien Leader, The New Black: Mourning, Melancholia, and Depression, 87.

- Darien Leader, The New Black: Mourning, Melancholia, and Depression, 93.

- Darien Leader, The New Black: Mourning, Melancholia, and Depression, 28.